[Important Notice: If any reader posts a comment, and does not see it after a couple of days, please will he or she contact me directly. In recent weeks, the number of spam comments posted to the site increased to over a thousand a day, all of which I had to investigate, and then approve or reject, which was a highly time-consuming process. I have now installed some spam-prevention software, but it is possible, I suppose, that the software will trap some genuine comments. Thank you.]

A Rootless Cosmopolitan

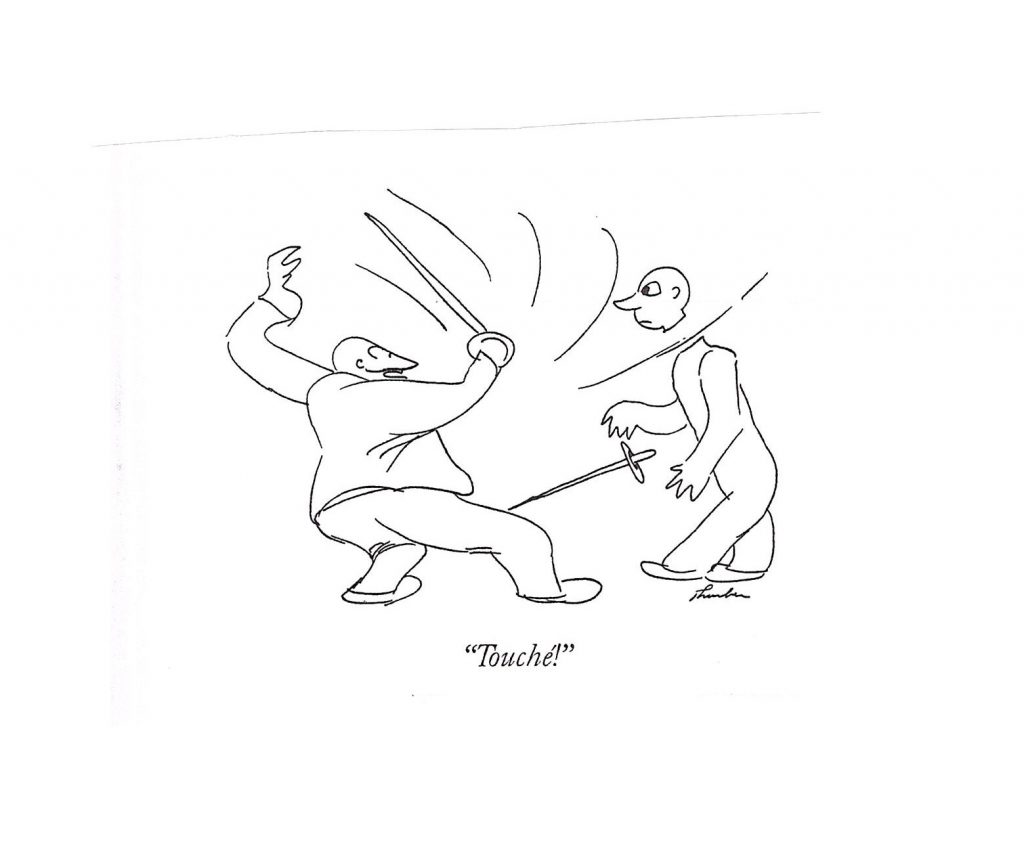

A few weeks ago, at the bridge table at St. James, I was chatting between rounds, and my opponent happened to say, in response to some light-heated comment I made: ‘Touché!’ Now that immediately made me think of the famous James Thurber cartoon from the New Yorker, and I was surprised to learn that my friend (who has now become my bridge partner at a game elsewhere) was not familiar with this iconic drawing. And then, a few days ago, while at the chiropractor’s premises, I happened to mention to one of the assistants that one of the leg-stretching pieces of equipment looked like something by Rube Goldberg. (For British readers, Goldberg is the American equivalent of W. Heath Robinson.) The assistant looked at me blankly: she had never heard of Goldberg.

I recalled being introduced to Goldberg soon after I arrived in this country. But ‘Touché’ took me back much further. It set me thinking: how had I been introduced to this classic example of American culture? Thurber was overall a really poor draughtsman, but this particular creation, published in the New Yorker in 1932, is cleanly made, and its impossibly unrealistic cruelty did not shock the youngster who must have first encountered it in the late 1950s. A magazine would probably not get away with publishing it these days: it would be deprecated (perhaps like Harry Graham’s Ruthless Rhymes for Heartless Homes) as a depiction of gratuitous violence, likely to cause offence to persons of a sensitive disposition, and also surely deemed to be ‘an insult to the entire worldwide fencing community’.

Was it my father who showed it to me? Freddie Percy was one of the most serious of persons, but he did have a partiality for subversive wit and humour, especially when it entered the realm of nonsense, so long as it did not involve long hair, illicit substances, or sexual innuendo. I recall he was fan of the Marx Brothers, and the songs of Tom Lehrer, though how I knew this is not certain, as we had no television in those days, and he never took us to see a Marx Brothers movie. Had he perhaps heard Tom Lehrer on the radio? He also enjoyed the antics of Victor Borge (rather hammy slapstick, as far as I can remember) as well as those of Jacques Tati, and our parents took my brother, sister and me to see the films of Danny Kaye (The Secret Life of Walter Mitty – from a Thurber story – and Hans Christian Andersen), both of which, I must confess, failed to bowl me over.

What was it with these Jewish performers? The Marx Brothers, Lehrer, Borge (né Rosenbaum) and Kaye (né Kaminsky)? Was the shtick my father told us about the Dukes of Northumberland all a fraud, and was his father (who in the 1920s worked in the clothes trade, selling school uniforms that he commissioned from East London Jewish tailors) perhaps an émigré from Minsk whose original name was Persky? And what happened to my grandfather’s Freemason paraphernalia, which my father kept in a trunk in the attic for so long after his death? It is too late to ask him about any of this, sadly. These questions do not come up at the right time.

I may have learned about Thurber from my brother. He was a fan of Thurber’s books, also – volumes that I never explored deeply, for some reason. Yet the reminiscence set me thinking about the American cultural influences at play in Britain in the 1950s and 1960s, and how they corresponded to local traditions.

Movies and television did not play a large part in my childhood: we did not have television installed until about 1965, so my teenage watching was limited to occasional visits to friends, where I might be exposed to Bonanza or Wagon Train, or even to the enigmatic Sergeant Bilko. I felt culturally and socially deprived, as my schoolmates would gleefully discuss Hancock’s Half Hour, or Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, and I had no idea what they were talking about. (It has taken a lifetime for me to recover from this feeling of cultural inferiority.) I did not attend cinemas very often during the 1950s, although I do recall the Norman Wisdom escapades, and the Doctor in the House series featuring Dirk Bogarde (the dislike of whom my father would not shrink from expressing) and James Robertson Justice. Apart from those mentioned above, I do not recall many American films, although later The Searchers made a big impression, anything with Audrey Hepburn in it was magical, and I rather unpredictably enjoyed the musicals from that era, such as Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, Oklahoma!, Carousel, and The King and I.

It was perhaps fortunate that I did not at that stage inform my father that I had suddenly discovered my calling in the roar of the greasepaint and the smell of the crowd, as the old meshugennah might have thrown me out of Haling Park Cottage on my ear before you could say ‘Jack Rubenstein’. In fact, the theatre had no durable hold on me, although the escapist musical attraction did lead me into an absorption with American popular music, which I always thought more polished and more stimulating than most of the British pap that was produced. (I exclude the Zombies, Lesley Duncan, Sandy Denny, and a few others from my wholesale dismissal.) Perhaps seeing Sonny and Cher perform I Got You Babe, or the Ronettes imploring me to Be My Baby, on Top of the Pops, led me to believe that there was a more exciting life beyond my dreary damp November suburban existence in Croydon, Surrey: California Dreaming reflected that thwarted ambition.

We left the UK in 1980, and, despite my frequent returns while I was working, and during my retirement, primarily for research purposes, my picture of Britain is frozen in a time warp of that period. Derek Underwood is wheeling away from the Pavilion End, a round of beers can be bought for a pound, the Two Ronnies are on TV, the Rolling Stones are just about to start a world tour, and George Formby is performing down the road at the Brixton Essoldo. [Is this correct? Ed.] I try to stay current with what is going on in the UK through my subscriptions to Punch (though, as I think about it, I haven’t received an issue for quite a while), Private Eye (continuous since 1965), the Spectator (since 1982), and Prospect (a few years old), but, as each year goes by, a little more is lost on me.

We are just about to enter our fortieth year living in the USA. As I wrote, we ‘uprooted’ in 1980, although at the time we considered that the relocation would be for just a few years, to gain some work experience, and see the country, before we returned to the UK. My wife, Sylvia, and I now joke that, once we have settled in, we shall explore the country properly. We retired to Southport, North Carolina, in 2001, and have thus lived here longer than in any other residence. Yet we have not even visited famous Charleston, a few hours down the road in South Carolina, let alone the Tennessee border, which is about seven hours’ drive away. (The area of North Carolina is just a tad smaller than that of England.) We (and our daughter) are not fond of long journeys in the car, which seems to us a colossal waste of time overall, and I have to admit there is a sameness about many American destinations. And this part of the world is very flat – like Norfolk without the windmills. You do not drive for the scenery.

Do I belong here? Many years ago we took up US citizenship. (I thus have two passports, retaining my UK affiliation, but had to declare primary loyalty to the USA.) My accent is a giveaway. Whereas my friends, when I return to the UK, ask me why I have acquired that mid-Atlantic twang, nearly everyone I meet over here comments that ‘they like my accent’ – even though some have been known to ask whether it is Australian or South African. (Hallo! Do I sound like Crocodile Dundee?) Sometimes their curiosity is phrased in the quintessential American phrase: ‘Where are you from?’, which most Americans can quickly respond to with the name of the city where they grew up. They may have moved around the country – or even worked abroad – but their family hometown is where they are ‘from’.

So what do I answer? ‘The UK’ simplifies things, but is a bit dull. To jolly up the proceedings, I sometimes say: ‘Well, we are all out of Africa, aren’t we?’, but that may unfortunately not go down well with everyone, especially in this neck of the woods. Facetiousness mixed with literal truth may be a bit heady for some people. So I may get a bit of a laugh if I respond ‘Brooklyn’, or even ‘Connecticut’, which is the state we moved to in 1980, and the state we retired from in 2001 (and whither we have not been back since.)

What they really want to know is where my roots lie. Now, I believe that if one is going to acknowledge ‘roots’, they had better be a bit romantic. My old schoolfriend Nigel Platts is wont to declare that he has his roots in Cumbria (wild borderlands, like the tribal lands of Pakistan, Lakeland poets: A-), while another old friend, Chris Jenkins, claims his are in Devon (seafarers, pirates, boggy moors: B+). My wife can outdo them both, since she was born in St. Vincent (tropical island, volcano, banana plantations: A+). But what do I say? I grew up in Purley, Coulsdon, and South Croydon, in Surrey: (C-). No one has roots in Purley, except for the wife of the Terry Jones character in the famous Monty Python ‘Nudge Nudge’ sketch. So I normally leave it as ‘Surrey’, as if I had grown up in the remote and largely unexplored Chipstead Valley, or in the shadow of Box Hill, stalking the Surrey Puma, which sounds a bit more exotic than spending my teenage years watching, from a house opposite the AGIP service station, the buses stream along the Brighton Road in South Croydon.

Do I carry British (or English) culture with me? I am a bit skeptical about these notions of ‘national culture’. One might summarise English culture by such a catalogue as the Lord’s test-match, sheepdog trials, pantomime, fish and chips, The Last Night of the Proms, the National Trust, etc. etc., but then one ends up either with some devilish discriminations between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture or with a list of everything that goes on in the country, which makes the whole exercise pointless. And what about ‘European’ culture? Is there such a thing, apart from the obvious shared heritage and cross-influences of music, art and literature? Bullfights as well as foxhunting? Bierfests alongside pub quizzes? The Eurovision Song Contest? Moreover, all too often, national ‘culture’ ends up as quaint customs and costumes put on for the benefit of the tourists.

Similarly, one could try to describe American culture: the Superbowl, revivalist rallies, Fourth of July parades, rodeos, NASCAR, Thanksgiving turkey. But where does the NRA, or the Mormon Church (sorry, newly branded as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints), fit in? Perhaps the USA is too large, and too new, to have a ‘national culture’. Some historians have claimed that the USA is actually made up of several ‘nations’. Colin Woodard subtitled his book American Nations ‘A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America’, and drew on their colonial heritages to explain some mostly political inclinations. Somewhat of an oversimplification, of course, as immigration and relocation have blurred the lines and identities, but still a useful pointer to the cultural shock that can occur when an employee is transplanted from one locality to another, say from Boston to Dallas. Here, in south-eastern North Carolina, retirees from Yankeedom frequently write letters to the newspaper expressing their bewilderment and frustration that local drivers never seem to use their indicators before turning, and habitually drive below maximum speed in the fast lane of the highway. The locals respond, saying: “If you don’t like how we do things down here, go back to where you came from!”.

And then is the apparent obsession in some places about ‘identity’ and ‘ethnicity’. The New York Times, leading the ‘progressive’ (dread word!) media, is notorious on this matter, lavishly publishing streams of Op-Ed articles and editorial columns about ‘racial’ identities and ‘ethnic’ exploitation. Some of this originates from the absurdities of the U.S. Census Bureau, with its desperate attempts to categorise everybody in some racial pigeonhole. What they might do with such information, I have no idea. Shortly after I came to this country, I was sent on a management training course, where I was solemnly informed that I was not allowed to ask any prospective job candidate what his or her ‘race’ was. Ten minutes later, I was told that Human Resource departments had to track every employee’s race so that they could meet Equal Employment Opportunity Commission guidelines. So it all depended on how a new employee decided to identify him- or her-self, and the bureaucrats got to work. I might have picked ‘Pacific Islander’, and no-one could have questioned it. (Sorry! I meant ‘Atlantic Islander’ . . .) Crazy stuff.

A few weeks ago, I had to fill out one of those interminable forms that accompany the delivery of healthcare in the USA. It was a requirement of the March 2010 Affordable Care Act, and I had to answer three questions. “The Government does not allow for unanswered questions. If you choose not to disclose the requested information, you must answer REFUSED to ensure compliance with the law”, the form sternly informed me. (I did not bother to inquire what would happen to me if I left the questions unanswered.) The first two questions ran as follows:

1. Circle the one that best describes your RACE:

- American Indian or Alaska native

- Asian

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander

- Black or African American

- White

- Hispanic

- Other Race

- REFUSED

2. Circle the one that best describes your ETHNICITY:

a. Hispanic or Latin

b. Non-Hispanic or Non-Latin

c. REFUSED

What fresh nonsense is this? To think that a panel of experts actually sat down around a table for several meetings and came up with this tomfoolery is almost beyond belief. (You will notice that the forms did not ask me whether the patient was an illegal immigrant.) But this must be one of the reasons why so many are desperate to enter the country – to have the opportunity to respond to those wonderful life-enhancing questionnaires created by our government.

This sociological aberration leaks into ‘identity’, the great hoax of the 21st century. A few weeks ago, the New York Times published an editorial in which it, without a trace of irony, announced that some political candidate in New York had recently identified herself as ‘queer Latina’, as if that settled the suitability of her election. The newspaper’s letter pages are sprinkled with earnest and vapid statements from subscribers who start off their communications on the following lines: “As a bald progressive Polish-American dentist, I believe that . . . .”, as if somehow their views were not free, and arrived at after careful reflection, but conditioned by their genetic material, their parents, their chosen career, and their ideological group membership, and that their status somehow gave them a superior entitlement to voice their opinions on the subject of their choice. (I believe the name for this is ‘essentialism’.) But all that is irrelevant to the fact of whether they have anything of value to say.

The trouble is that, if we read about the views of one bald progressive Polish-American dentist, the next time we meet one of his or her kind, we shall say: “Ah! You’re one of them!”, and assume that that person holds the same opinions as the previously encountered self-appointed representative of the bald progressive Polish-American dentist community. And we end up with clumsy stereotypes, which of course are a Bad Thing.

Identity should be about uniqueness, not groupthink or unscientific notions of ethnicity, and cannot be defined by a series of labels. No habits or practices are inherited: they are all acquired culturally. That doesn’t mean they are necessarily bad for that reason, but people need to recognize that they were not born on predestinate grooves to become Baptists or Muslims, to worship cows, to practice female circumcision, or to engage in strange activities such as shooting small birds in great numbers, or watching motor vehicles circle an oval track at dangerous speeds for hours on end, in the hope that they will at some time collide, or descending, and occasionally falling down on, snowy mountainsides with their feet buckled to wooden planks, while doing their best to avoid trees and boulders. It is not ‘in their blood’, or ‘in their DNA’.

Social workers are encouraged (and sometimes required) to seek foster-parents for adoption cases that match the subject’s ‘ethnicity’, so as to provide an appropriate cultural background for them, such as a ‘native American’ way of life. Wistful and new-agey adults, perhaps suffering from some disappointment in career or life, sometimes seek out the birthplace of a grandparent, in the belief that the exposure may reveal some vital part of their ‘identity’. All absolute nonsense, of course.

For instance, I might claim that cricket is ‘in my DNA’, but I would not be able to tell you in what epoch that genetic mutation occurred, or why the gene has atrophied in our rascally son, James, who was brought to these shores as a ten month-old, and has since refused to show any interest whatsoever in the great game. On the other hand, did the young Andrew Strauss dream, on the banks of the blue Danube, of opening the batting for England? Did Michael Kasprowicz learn to bowl outswingers in the shadow of the Tatra Mountains?

Yet this practice of pigeon-holing and stereotyping leads to deeper problems. We now have to deal with the newly discovered injustice of ‘cultural appropriation’. I read the other day that student union officials at the University of East Anglia had banned the distribution of sombreros to students, as stallholders were forbidden from handing out ‘discriminatory or stereotypical imagery’. Well, I can understand why Ku Klux Klan hoods, and Nazi regalia, would necessarily be regarded as offensive, but sunhats? Were sombreros introduced by the Spanish on reluctant Aztecan populations, and are they thus a symbol of Spanish imperialism? Who is actually at risk here? What about solar topis? Would they be banned, too?

We mustn’t stop there, of course. Is the fact that Chicken Tikka Masala is now viewed by some as a national British dish an insult to the subcontinent of India, or a marvellous statement of homage to its wonderful cuisine? Should South Koreans be playing golf, which, as we know, is an ethnic pastime of the Scots? Should non-Maori members of the New Zealand rugby team be dancing the haka? English bands playing rhythm ‘n’ blues? Should Irving Berlin have written ‘White Christmas’?

The blight has even started to affect the world of imaginative fiction. I recently read, in the Times Literary Supplement, in an article on John Updike, the following: “Is self-absorbed fiction always narcissistic, or only if it’s written by a straight white male? What if it’s autofiction, does that make it ok? What are the alternatives? If a writer ventures outside their own socio-cultural sphere, is that praiseworthy empathy or problematic cultural appropriation? Is Karl Ove Knausgaard more self-absorbed than Rachel Cusk? Is that a good thing or a bad thing?” (‘Autofiction’ was a new one on me, but it apparently means that you can invent things while pretending to write a memoir, and get away with it. Since most autobiographies I have read are a pack of lies planned to glorify the accomplishments of the writer, and paper over all those embarrassing unpleasantnesses, I doubt whether we need a new term here. Reminiscences handed down in old age should more accurately be called ‘oublioirs’.)

The writer, Claire Lowdon, almost nails it, but falls into a pit of her own making. ‘Socio-cultural sphere’? What is that supposed to mean? Is that a category anointed by some policepersons from a Literary Council, like the Soviet Glavlit, or is it a classification, like ‘Pacific Islander’, that the author can provide him- or her-self, as with ‘gay Latina’? Should Tolstoy’s maleness, and his ‘socio-cultural sphere’, have prevented him from imagining the torments of Anna Karenina, or portraying the peasant Karatayev as a source of wisdom? The defenders of culture against ‘misappropriation’ are hoist with the petard of their own stereotypes. (And please don’t ask me who Karl Ove Knausgaard and Rachel Cusk are. Just because I know who John Updike, James Thurber and Rube Goldberg are, but fall short with these two, does not automatically make me nekulturny, and totally un-cool.)

The whole point of this piece is to emphasise the strengths and importance of pluralism, and diminish the notion of multiculturalism. As I so urbanely wrote in Chapter 10 of Misdefending the Realm: “In a pluralist society, opinion is fragmented – for example, in the media, in political parties, in churches (or temples or mosques), and between the legislative and the executive arms of government. The individual rights of citizens and their consciences are considered paramount, and all citizens are considered equal under the law. The ethnic, cultural, religious or philosophical allegiances that they may hold are considered private affairs – unless they are deployed to subvert the freedoms that a liberal society offers them. A pluralist democracy values very highly the rights of the individual (rather than of a sociologically-defined group), and preserves a clear line between the private life and the public sphere.”

Thus, while tracing some allegiance to the cultures of both the UK and the USA, I do not have to admit to interest in any of their characteristic practices (opera, horse-racing, NASCAR, American football, Game of Thrones, etc. etc.) but can just quietly go about my business following my legal pursuits, and rejoice in the variety and richness of it all.

It was thus refreshing, however, to find elsewhere, in the same issue of the TLS, the following statement – about cricket. An Indian politician, Shashi Tharoor, wrote: “And yet, this match revealed once again that cricket can serve as a reminder of all that Indians and Pakistanis have in common – language, cuisine, music, clothes, tastes in entertainment, and most markets of culture, including sporting passions. Cricket underscores the common cultural mosaic that brings us together – one that transcends geopolitical differences. This cultural foundation both predates and precedes our political antipathy. It is what connects our diasporas and why they find each other’s company comforting in strange lands when they first emigrate – visibly so in the UK. Cricket confirms that there is more that unites us than divides us.”

Well, up to a point, Lord Ram. That claim might be a slight exaggeration and simplification, avoiding those tetchy issues about Hindu-based nationalism, but no matter. Cricket is a sport that was enthusiastically picked up – not appropriated – in places all around the world. I cannot be the only fan who was delighted with Afghanistan’s appearance in the recent World Cup, and so desperately wanted the team to win at least one game. I have so many good memories of playing cricket against teams from all backgrounds (the Free Foresters, the Brixton West Indians, even the Old Alleynians), never questioning which ‘socio-cultural sphere’ they came from (okay, occasionally, as those readers familiar with my Richie Benaud experience will attest), but simply sharing in the lore and traditions of cricket with those who love the game, the game in which, as A. G. McDonnell reminded us in England Their England, the squire and the blacksmith contested without class warfare getting in the way. Lenin was said to have despaired when he read that policemen and striking miners in Scotland took time off from their feuding to play soccer. He then remarked that revolution would never happen in the UK.

For a while, I considered myself part of that very wholesome tradition. I was looking forward, perhaps, to explaining one day to my grandchildren that I had watched Cowdrey and May at the Oval (‘Oh my Hornby and my Barlow long ago . . .’), and that I could clearly recall an evening in late July 1956 where I overheard a friend of my father’s asking him whether he had heard that ‘Laker took all ten’. But Ashley, and the twins Alexis and Alyssa (one of their maternal great-grandfathers looked just like Ho Chi Minh, but was a very gentle man with no discernible cricket gene in his make-up) would surely give me a quizzical look, as if it were all very boring, and ask me instead to tell them again the story of how I single-handedly tracked down the Surrey Puma . . .

Uprooted and rootless I thus remain. My cosmopolitan days are largely over, too. Even though I have never set my eyes on Greenland’s icy mountains or India’s coral strand (or Minsk), I was fortunate enough to visit all five continents on my business travels. I may still make the occasional return to the United Kingdom: otherwise my voyages to major metropolitan centres are restricted to visits to Wilmington for appointments with the chiropractor, and cross-country journeys to Los Altos, California to see James and his family.

So where does that leave me, and the ‘common cultural mosaic that binds us together’? A civilized culture should acknowledge some common heritage and shared customs, while allowing for a large amount of differences. Individuals may have an adversarial relationship in such an environment, but it should be based on roles that are temporary, not essentials. Shared custom should prevent the differences becoming destructive. Yet putting too many new stresses on the social fabric too quickly will cause it to fray. For example, returning to the UK has often been a strange experience, revealing gradual changes in common civilities. I recall, a few years ago, walking into the branch of my bank in South Croydon, where I have held an account since 1965. (The bank manager famously gave me what I interpreted as a masonic handshake in 1971, when I was seeking a loan to ease my entry into the ‘property-owning classes’.) The first thing I saw was a sign on the wall that warned customers something along these lines: “Abuse of the service staff in this bank will not be tolerated! Offenders will be strictly prosecuted.”

My, oh my, I thought – does this bank have a problem! What a dreadful first impression! Did they really resent their customers so much that they had to welcome them with such a hostile message? Was the emotional well-being of their service staff that fragile? Did the bank’s executives not realise that customer service requires a thick skin? And perhaps behind all that lay a deeper problem – that their customer service, and attentiveness to customers’ needs, were so bad that customers too often were provoked into ire? Why would they otherwise advertise that fact to everyone who walked in?

I can’t see that happening in a bank in the United States, where I am more likely to receive the well-intentioned but cringe-making farewell of ‘Have a blessed day!’ when I have completed my transaction. That must be the American equivalent of the masonic handshake. (No, I don’t do all my bank business via my cell-phone.) Some edginess and lack of trust appear to have crept in to the domain of suburban Surrey – and maybe beyond. Brexit must have intensified those tensions.

Another example: In North Carolina, when walking along the street, we residents are in the habit of engaging with strangers as we pass them, with a smile, and a ‘Good Day!’, or ’How are you doin’?’, just as a measure of reinforcing our common civility and good humour. When I last tried that, walking around in South Croydon, where my roots are supposed to be, it did not work out well. I got a scared look from an astonished local, as if to say: ‘Who’s that weird geezer! He clearly doesn’t belong here’. And he would be right.

In conclusion: a list. As a retired Anglo-American slightly Aspergerish atheist ex-database administrator, I love lists, as all persons with the above description predictably do. My choice below catalogues fifty cultural figures (including one pair) who have influenced me, or for whom I hold some enthusiasm, a relationship occasionally enhanced by a personal encounter that contained something special. (I should point out, however, that I was brought up in a milieu that stressed the avoidance of showing excessive enthusiasm: ‘Surtout, pas trop de zèle!’. Somehow I survived American business without being ‘passionate’ about anything.) That does not mean that these persons are idols, heroes, icons, or role-models – they simply reflect my enthusiasms and tastes. But they give an idea of how scattered and chaotic any one person’s cultural interests can be in a pluralist society. Think of them as my cosmopolitan roots. Rachel Cusk did not make the list, but she would probably have beaten out J. R. R. Tolkien and Eric Hobsbawm.

Kingsley Amis

Jane Archer

John Arlott

Correlli Barnett

Raymond Chandler

Anton Chekhov

John Cleese

Robert Conquest

Peter Cook

Peter Davison

Theodor Fontane

Milton Friedman

Alan Furst

Peter and Rosemary Grant

Robert Graves

Emmylou Harris

Friedrich Hayek

Audrey Hepburn

Ronald Hingley

Clive James

Paul Jennings

Gordon Kaufmann

Hugh Kingsmill

Heinrich von Kleist

Arthur Koestler

Osbert Lancaster

Philip Larkin

Stephen Leacock

Fitzroy Maclean

D. S. Macnutt

René Magritte

Nadezhda Mandelstam

John Martin

Peter Medawar

H. L. Mencken

Christian Morgenstern

George Orwell

Arvo Pärt

Sergey Rachmaninov

Joseph Roth

Peter Sellers

Eric Shipton

Posy Simmons

Joe Simpson

Wilfred Thesiger

Alan Turing

Immanuel Velikovsky

Carolyn Wells

Michael Wharton

P. G. Wodehouse

(New Commonplace entries can be found here.)

Thank you for this delightful excursion – many wise words and a splendid list of influencers with few of whom I would disagree. It is particularly flattering to be named in my Cumbrian guise: please remember it is for me Cumberland not the post reorganisation Cumbria which, of course, includes Westmorland and parts of Lancashire and Yorkshire. My birthplace was Whitehaven famous for Fletcher Christian of The Bounty and John Paul Jones of the US Navy – real Cumberland!

Thank you so much, Nigel! Perhaps your clarification of Old Cumbria and its scions should raise you a few notches on the Romantic scale?