I take a break from intelligence matters this month to celebrate Sylvia’s and my forty-fifth wedding anniversary, and to exploit the occasion by indulging in some mostly reliable reminiscences and reflecting upon them.

* * * * * * * * * *

On occasions, when conversing with Americans at social gatherings, I am asked at which ‘school’ (= ‘college’) I was educated. When I reply ‘Christ Church, Oxford’, a beatific smile sometimes takes over the face of my interlocutor, as if he (or she) believed that Christ Church was the British equivalent of Oral Roberts University, and they start thinking about whether they should invite me to be one of their lay preachers or readers at the local Methodist or Episcopalian Church. I am always quick to ward them off any such idea, as I do not believe I would delight their congregation, and it normally turns out that, when I start explaining the peculiar history of Christ Church (the ‘House’ – Aedes Christi, and never referred to as ’Christ Church College’), and its role as an independent college in the Oxford University framework, their eyes start to glaze over, and they look instead for someone they can discuss the football with.

1952-1956

But there was a time! I happened recently to retrieve from my archives my Report Cards from my years at St. Anne’s Preparatory School in Coulsdon, Surrey, for the years 1952 to 1956. In my Kindergarten report of Summer 1952, Mrs. Early’s assessment for ‘Scripture’ runs: ‘Listens to Bible Stories with interest’. Was this true absorption? Or a well-managed bluff? Or a view of astonishment? I cannot recall. A year later, I was third in the exams, although I dropped to sixth by Christmas. The following summer, there was apparently no exam, but it was recorded that I ‘attended morning assembly regularly’. I suspect I did not have a choice, but maybe others did? By Summer 1955, ‘Scripture’ had been replaced by ‘Divinity’, and I achieved a creditable second place in the exams, followed by more excellent results. But then, in my last term, in Summer 1956, I dropped to 18th in the standings, from a class of 27. ‘Very fair’, was the comment, which is English-teacher speak for ‘pretty awful’. What had happened? Obviously a crisis of faith had occurred. And it happened because of a convergence of music and history.

I had been intrigued by the History lessons, where we learned about Cavemen, and the Stone Age, and perhaps I found these a more plausible account of the Birth of Man than the rather saccharine Bible Stories. At about the same time, I recall we had music and singing lessons, where we were encouraged to trill lustily some English (and Irish, Scottish and Welsh) folksongs. Apart from such standbys as ‘Bobbie Shaftoe’, I particularly remember two songs: the first one that I had for long imagined was by Rabbie Burns – ‘A-Rovin’’, the second, ‘Greensleeves’. Looking the former up today, I see that its title is ‘The Maid of Amsterdam’, and is a traditional sea shanty that first appeared in London, in 1608, in a play by Robert Heywood. The chorus went as follows:

A-rovin’, a -rovin’, since rovin’s been my ru-i-in

I’ll go no more a-rovin’ with you – fair – maid.

I can recall to this day the atmosphere in the classroom as we took up the refrain, with the smell of cabbage and dirty socks wafting in from other rooms, and my seat, bottom left, where I was always trying to catch the teacher’s attention.

But isn’t that extraordinary – that a prim preparatory school in postwar England would encourage its eight-year-olds to sing about ‘roving’? Assuredly we did not sing the whole song, as I note that the third verse runs as follows:

I put my hand upon her thigh

Mark well what I do say

I put my hand upon her thigh

She said: “Young man you’re rather high!”

I’ll go no more a-rovin’ with you fair maid

Needless to say, we did not get further than the first verse, but I think I was already enthused enough to think that this roving business was something I needed to investigate. I now wonder whether I already had at that time enough imagination to reflect that wasn’t it more likely that the Fair Maid would face Ruin than the Rover would? I was certainly not looking for ruination at that age, but I was very keen to learn more about this frightening prospect, and how beautiful maidens could indeed be the cause of the complete collapse into desolation or penury of innocent young lads like me.

But where to find ‘fair maids’? My father owned a handsome, tall, glass-lined – but locked – bookcase, and I could inspect the titles there through the panes. One title was The Fair Maid of Perth, which sounded promising. Perhaps Perth was a fertile location for the incipient Rover? So I looked up ‘Perth’ in the atlas: it seemed a bit far away. Requiring quite a substantial rove, in fact. My absence might have been noted, and I would have been pushed to get back in time for my favourite baked-beans-on-toast supper, so I abandoned that plan. Another potential source was Roy Race, of Melchester Rovers, who featured in Tiger magazine, but I soon saw that his adventures did not involve exploits with girls but instead such feats as rescuing the Rovers’ French import, Pierre Dupont, from a lighthouse where he had been kidnapped, so that they could get him back in time for kick-off. (“Who’d play the Rovers with Pierre on our wing ?” Tra-la-la.) All stirring stuff, of course, but not really relevant to the Quest.

And then there was Greensleeves. That glorious tune, and the illustrations, at the back of some encyclopædia or annual that I possessed, that showed a comely young girl, draped in muslin or something similar, sitting on a bough of a tree in some medieval forest. Was Greensleeves one of those maids who could ruin you? She didn’t look as if she were someone who could cause permanent damage. At the same time, I couldn’t see myself taking her home to meet Mum and Dad. (“Sit down, dear, and have a cup of tea. But why is your frock all green? Have you been frolicking in the grass?”) Nevertheless, maybe it would have been safe to do a little roving with her, to see what it was like, without getting into trouble.

Another permanent memory is attending Sunday School. I would inwardly seethe at being sent off, on an afternoon when playing outside beckoned far more energetically, to the church at the top of the hill in Coulsdon, Surrey. (It was St. Andrew’s, where my parents were married in August 1940, as the bombs started falling.) It was utterly boring, and prominent among the tedious exercises that we had to carry out was the recitation of the Apostles’ Creed, which, even then, I regarded as the most ridiculous mumbo-jumbo I had ever heard. (This was especially so with the St. James version in use then, that contained ‘the Holy Ghost’, ‘hell’, and ‘the quick and the dead’, making it particularly opaque.) It was never explained to us what these statements meant, how they were derived, or why they were important. We were just indoctrinated: “I believe in . . .”. I fail consistently to understand how any inquisitive child would not rebel against such nonsense, and the way it was drilled into us. But eight-year-olds in my world did not ask questions. We did what we were told. Moreover, the girls at Sunday School were all very soppy and outwardly very pious. Not a single green sleeve to be found among the lot of them.

But to return to school. At the end of one of the lessons, probably in the spring of 1956, I went up to speak to Mr. Robinson and Mr. Wilder, who for some reason were both present during the session. Mr. Robinson was a kindly, Pickwickian figure, who blinked at us, and always wore a three-piece-suit with a fob watch in his waistcoat. He taught us English and History. Mr. Wilder was much younger, tall and athletic, half-French. He taught Arithmetic, French, and sport, and impressed me and other pupils once when he said he could think in French. I had two questions for the pair of them: Who wrote ‘Greensleeves’? And which account of Man’s origins was right – the Garden of Eden or the Story of the Cavemen?

Mr. Robinson and Mr. Wilder looked at each other awkwardly. The Greensleeves question they were able to dispense with fairly quickly: ‘traditional’, ‘no known composer’, but the other one was challenging. I am not sure exactly what they said: they may have used the word ‘allegory’, but probably not, but I do recall having the impression that I should not take those Bible stories all very literally. And I think that did it for me, as far as religion was concerned. They confirmed for me that it was all bogus. I had sorted out something significant, and from that day on, I knew what I wanted to do. When cringe-making friends of my parents patted me on the head, and asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I would say I wanted to be an ‘influencer’, and would seek to monetise my content-creation as soon as I could. (That quickly shut them up.) Unfortunately it took sixty-five years for that idea to take off.

Now, I have to say that I was a very literal-minded little boy at that stage. I had great problems differentiating between fiction and reality, and no one had yet introduced me to William Empson and his Seven Types of Ambiguity. For example, I recall seeing the advertisement for Johnny Walker whisky on the front page of the Illustrated London News, where the slogan declared: ‘Born 1820. Still going strong!’, and it displayed a regency gentleman, in red jacket, shiny black boots, and a golden top-hat breezily striding somewhere. 1954 minus 1820 was 134. How could a man live to be that long, I asked myself, and where could I meet him?

And then there were the movies (pictures). We went to see The Blue Lamp, where Jack Warner played P.C. Dixon, and was eventually shot by the Dirk Bogarde character. (It came out in 1950. Did I really see it that early?) I was distraught. The very likable policeman was dead, definitely not ‘still going strong’, and it must have been ages before it was explained to me that it was all illusory. About that time we must also have seen a trailer for King Kong (children would not have been allowed to watch the full movie), and I had nightmares for months, since I believed that great apes could actually grow to that size and might terrorize our neighbourhood. And I know I was puzzled about ‘The Dark Ages’, concluding that for hundreds of years the sun did not come out, and people must have groped around in the murkiness until the light returned.

I recall, also, my bewilderment over my father’s occupation during the day. He would set off on his bicycle to school each day (a journey of about five miles along the busy Brighton Road), but I could not work out why a man of his age was still attending school. My sister eventually explained to me that he was not a pupil there, but a teacher. Somehow, even though I saw men of his age teaching at St. Anne’s, I had never made the connection.

Yet that summer of 1956 must have been very important. I remember being introduced to the Daily Telegraph cryptic crossword, and solving my first clue. (The answer was ‘OSCAR’.) I discovered – and delighted in – nonsense verse. I recall being fascinated by my father’s meagre store of one-liners, such as ‘She was a good cook, as cooks go, but, as cooks go, she went’, and was exceedingly happy to sort out why the linguistic twist worked, and why it made me laugh. I suddenly started to appreciate allusion, metaphor, irony, bathos, and paradox. The real world was far more subtle and multi-layered than I had ever imagined. At the same time, I felt a distinct disdain for the mythical and the mystical, a distaste that has never gone away. (The Greek Myths left me cold, as did C.S. Lewis and Tolkien. Though I loved Arthur Ransome’s Old Peter’s Russian Tales.) But not the mysterious: mystery was captivating. And Greensleeves lay in the field of mystery.

1956-1965

In September 1956 I started at Whitgift School in Croydon. Like many such independent schools, it had a charitable foundation, and the assumption seemed to be that all the pupils should be trained to be solid Christian gentlemen. That was assuredly something that the Headmaster, Geoffrey Marlar (who had ridden with the cavalry in WWI) believed. Coincident with my arrival at the school, our family had moved house – to more spacious accommodation rented from the school Foundation, on the playing-fields, about four hundred yards from the Headmaster’s house. If, on a Sunday, my brother and I played any ball-game that caused us to stray far from Haling Park Cottage, and Marlar espied us while gardening, he would shake a fist at us for breaking the Sabbath, and our father would get a roasting from him the next day. I found this all very strange, and the arrival of Cavaliers cricket on Sundays soon afterwards must have dismayed Marlar. (He retired in 1961.)

I had to attend daily Assembly, careful to be carrying my hymnbook for inspection. (For one week when I had mislaid that item, I recall taking in a pocket dictionary, and not being spotted.) I would never even have thought of getting exempted as a pagan, but then I learned that there was a category of boys called ‘Jews’ who were allowed to sit it out. This seemed to me grossly unfair. I couldn’t tell why these characters were any different from the motley crew of youngsters from all quarters of Europe, both friendly and inimical, that I had to deal with, and thus could not work out why they were allowed to escape all the mumbo-jumbo. Later I would learn that there were atheist Jews, and agnostic Jews, and Protestant and Catholic Jews, and Jews for Jesus, and non-Jews who had converted for marital reasons, but it all seemed to me like an Enormous Category Mistake at the time, even though I had not worked out why. Much later, after looking into the matter, I decided that dividing the world into Jews and Gentiles was patently absurd, and I was encouraged to learn that Schlomo Sands (in The Invention of the Jewish People) gave historical authority to my doubts and inclinations.

Then I got recruited to the Choir. Not because I liked singing, but because I apparently had a decent voice, and obedient boys did not challenge what their elders and betters decreed. The only trouble was that the times for Choir Practice and Rugby Practice collided, and it was an easy decision for me to pick the activity I preferred. Thus, when the first performance of Iolanthe was staged, in December 1957 (I think), one Fairy who had missed out on the rehearsals was able to give a startling innovative and true-to-life interpretation of the first chorus ‘Tripping Hither, Tripping Thither’, something which my classmates were quick to point out to me the following morning. Mortification came easily.

Hymn- and carol-singing was, however, quite enjoyable, and even the less devout masters joined in lustily (with my father notoriously singing out of tune, another embarrassing fact that was swiftly communicated to me by one of his colleagues). But it was important not to study the words too closely. I do not know how many of us inquisitive ten- and eleven-year-olds worked out, when singing the stirring Adeste Fideles, what ‘Lo, he abhors not the virgin’s womb’ meant, but it was a line that Frederick Oakeley (if indeed it was he) should have stifled at birth when he faced the challenge of translating

Deum de Deo, lumen de lúmine,

gestant puellae viscera

Deum verum, genitum non factum.

What was extraordinary to me then, and remains so, is how many of the school staff, presumably intelligent and well-educated persons who were supposed to be encouraging their pupils to think critically, swallowed up such nonsense unquestioningly.

In fact my sister confided in me an awful truth, in about 1959. She told me that our father (not Our Father, I hasten to add, since His views on the matter are for ever indeterminable) did not believe in the Apostles’ Creed. What a shock! I was like: ‘Hallo!’, and in my best Holden Caulfield style responded that surely no one believed in that stuff any more. Why Daddy had vouchsafed this truth to my sister, and not to me, was a mystery, but I concluded that, in my resolve not to accompany the rest of the family to church, something they did only at Christmas and Easter, I had perhaps been working my ‘Influencer’ magic on him for the good. (Those who knew my father will know how unlikely a story that is.)

But back to the choir. After a while, my voice broke, of course, and I became an alto. Something was wrong, however, and I was jolted out of my complacency when a fellow chorister – name of Balcomb (where is he now?) – pointed out loudly, to no one in particular, that ‘Percy just sang the treble part one octave lower’. Apparently I was supposed to sight-read the alto part from the hymnal, and thus harmonise with the basses and tenors. But I couldn’t do that! No one had told me what to do, or taught me how to sight-read. Another colleague informed me that most of the choir actually sang at their church, where they learned such tricks, but that his main objective in joining the church had been ‘to meet girls’. So maybe that was the route to take! But there was no way that I was going to sacrifice my irreligious principles for a bit of skirt-chasing (‘that’s not who I am’), so the hunt for Greensleeves was temporarily abandoned, and the choir permanently discarded.

Yet my teenage years were filled with things that I really did not want to do. I had joined a local Scout group, because a new master at the school had a son my age who was keen, and my parents thought it was ‘a good idea’ for me to join. I was made by my unmusical parents to take up piano-playing, something I was not adept at. I hated practising, and dreaded the weekly lesson, dearly hoping that the scheduled time would clash with an away cricket match. Later came the Combined Cadet Force, much harder to avoid, as the alternative was the Boy Scouts, but Monday night, preparing my uniform for CCF day, was the most dismal evening of the week.

This all left very little time for roving. I attended the Yates-Williams School of Ballroom Dancing, at the Orchid Ballroom in Purely, but that was all rather chaotic, and dancing was not my shtick, either. No time for careful wooing of Greensleeves. And glimpses of such a life were few and far between. When we studied Molière’s Bourgeois Gentilhomme, I recall Henry Axton trying to make the play a little more spicy for us (I was fourteen at the time), by suggesting, in the scene where M. Jourdain meets Dorimène, that he was probably trying to look down her cleavage. This was unbearably saucy for my liking, but indicated that Mr. Axton probably knew a bit about roving. I did not seek him out after the class, however, to quiz him on the details.

Thus, by the time the Sixth Form Socials arrived, where the girls from the local high schools were invited, I was hopelessly disadvantaged. (Well, there had been a few romantic roving episodes – none of Turgenevian proportions, I should add – but I must stay silent about them, as any account would be too shy-making.) I bet all those blighters sporting ‘Crusader’ badges were winning the roving spoils. And, bewilderingly, the Religious Knowledge classes continued into the Lower Sixth Form, where a dreary three-quarters of an hour was wasted each week in studying some Bible extract, and poor Don Rose was brought into relative despair in trying to fire evangelical enthusiasm in the few obvious non-believers in the class. On the other hand, John Chester, our Sixth Modern form-master, as a dedicated Count Bernadotte internationalist, was perplexed at any admission of atheism, seeing it as a symptom of Communism. Presumably the same impulse that provoked the US Congress to adopt ‘In God We Trust’ as the national motto in 1956.

There were not many women at Whitgift. In the early years, we had Miss Scott in the Art Room, and the Headmaster’s secretariat contained two ladies, a very pleasant person called Mrs. Haynes, and her rather dour assistant whom we nicknamed ‘Olga’, as she looked as if she had just stepped out of a Chekhov play. In a sincere attempt to bring more joy to their lives, I posted the following clerihew on the Poetry Wall in the Prefects’ Room:

Mrs Haynes

Goes jiving in Staines,

While Olga

Dances the polga.

I do not know whether Life imitated Art in this particular case, but such musings formed a creative break from our cheerless studies.

The themes from the German literature we were given as set books were too frequently beyond the ken of secluded and protected sixteen-year-olds like me. Thus Gretchen’s passion and torment in Goethe’s Urfaust were rather bewildering (‘abhorrence of a virgin’s womb’? Mr. Chester would never have discussed sex or pregnancy with us), although the role of Mephistopheles in introducing Faust to Roving was unmistakably evil. (Was Gretchen’s “Meine Ruh’ ist hin” a ghostly echo of “my ru-i-in”?) And Goethe’s development of the ending, where Gretchen’s Old Testament fate (“ist gerichtet” – “judged”) evolved eventually to one of New Testament salvation (“ist gerettet” – “saved”) cut no ice with me. On the other hand, the Cambridge Examiners, in their fashionable wisdom, set the Communist Bertolt Brecht’s turgid Leben des Galilei as the second set book. Definitely no cleavages on view there. The last book, Heinrich von Kleist’s Der Prinz von Homburg, was an extraordinarily modern psychological study, Shakespearean in its combination of historical drama with study of period-independent human failings. It was thus for me the most accessible of the three set texts. Kleist died in a joint suicide with his Greensleeves, the mortally ill Henriette Vogel, in 1811. No more a-rovin’ for you, Heinrich old chap. But your work lives on: ‘Born 1777 – Still Going Strong’.

Thus a rather confused and hesitant candidate applied for entrance to Oxford University.

1965-1976

It was a strange business, landing up at Christ Church, of all places, the home of the Oxford Cathedral, and alma mater of countless Prime Ministers. My acceptance was surely not because of my scholastic record or potential, and I can only assume that they must have picked me for one of three reasons:

1) They thought I was a fairly close relative of the Duke of Northumberland, they hadn’t had many Percys enrolled in recent years, and imagined I might be a useful addition to the beagling set;

2) They hadn’t filled their quota of infidels for the year, and needed to take some immediate affirmative action to balance the numbers;

3) They needed a versatile rugby three-quarter, who could play fly-half, centre, or full-back, and preferably someone who could bowl a bit as well.

In fact, I may have been admitted through a misunderstanding. When I had my interview, one of the dons suddenly asked me: “Have you done any roving?”, to which I immediately piped up, replying: “Not much, but I certainly expect to take it up enthusiastically if I am accepted!”. One or two heads nodded at this, which was quite encouraging. It was not until a few hours later that it occurred to me that the distinguished academic had perhaps been impressed with my strapping 6’ 4” physique, and that the question might have been: “Have you done any rowing?”. I must have disappointed the Senior Common Room when I did not take my place on the boats.

Yet it was a bit of a culture shock. The cathedral was obviously a dominant presence, and there was a fairly vigorous Church Militant group from such places as Wellington and Marlborough. I was not even like the agnostic worshipper at the Cathedral quoted in Peter Snow’s Oxford Observed: “I am conscious of communicating if not with Christ then with the whole of English history and tradition.” And I soon found that I, as an obvious non-cathedral-service attendee, was to be excluded from some of the key social events – such as the Chaplain’s sherry parties. (Such discrimination would not be allowed in 2021, where chaplains, now probably called Spiritual Care and Outreach Officers, presumably have to administer to everyone, including Buddhists, Rosicrucians and atheists, and to attend to their emotional needs when they are offended by the presence of statues of benefactors of less than stellar integrity. And I notice that Harvard University recently appointed an atheist as its Head Chaplain.) One of my few god-fearing friends did however encourage me to gatecrash one of those parties, but I was sent away with a flea in my ear – not what I considered very charitable behaviour. Yet I learned one thing: One did not go to the Chaplain’s sherry parties to meet Greensleeves. No sirree.

But the theologians! I could not believe how many canons and readers and students of Theology there were. What on earth was ‘Theology’ and how could one pursue a course of study in it? The study of ‘God’ or of ‘gods’? Even today, when I pick up a recent copy of Christ Church Matters, the House magazine, I find that most of the books by Christ Church alumni that receive reviews are on matters of religion (e.g. ‘Theologically Engaged Anthropology’, ‘The Study of Ministry’, ‘Theology and Religion: Why It [sic] Matters’; ‘Interfaith Worship and Prayer: We Must Pray Together’; etc. What is going on? How can such superstition occupy so many serious minds for so much of their time? I find it astounding. And then there are the editorials from the Dean, written in language that has no meaning at all for persons like me.

This lesson was brought home to me recently when I read an article in Prospect, titled ‘How to Build a New Beveridge’. It was written by someone called Justin Welby, who I assumed was perhaps the offspring of Marcus Welby, M. D., until the footnote informed me that he apparently occupied a role described as ‘Archbishop of Canterbury’. Welby started his article as follows: “An apocryphal riddle for theology students goes thus: ‘Could God create a rock so heavy that God couldn’t lift it?’ The problem, of course, is that if God can’t, then he’s not omnipotent. If God can, he can’t lift it, and so he’s not omnipotent.” (The rest of the essay was a depressing parade of preachy homilies, worthy of Private Eye’s J. C. Flannel.)

Apocryphal, eh? We all know about the Apocrypha, don’t we, and how they relate to truly genuine canonical texts. So that is what theology students were doing to earn their degree, discussing nonsensical questions like that, while I was slaving away, doing really useful stuff, such as trying to make sense of the High German Consonant Shift, and exploring the use of symbols in Chekhov’s plays! It reminded me of that other no doubt apocryphal essay question on the PPE (Philosophy, Politics and Economics) finals paper at Oxford: “Is this a question?”. One candidate was inspired enough to write simply: “If it is a question, this is an answer”, and was awarded a First on account of it. That is presumably how the Church, the Cabinet, and the Foreign Office were staffed – with people who could so ably tackle such urgent questions, and such achievements led them on to believe that they could ‘solve’ the pressing problems of their time, like ‘the problem of social welfare.’ Harrumph.

‘But enough of politics, what about your social life?’, I hear you cry. Well, a little roving went on. I’d like to report that, as in Philip Larkin’s imaginings with the women he encountered in books, ‘I broke them up like meringues’, but that would not be strictly true, and the National Profiterole and Meringue Authority might have had something to say about such a micro-aggression. Yet I shall necessarily have to draw a veil over such activities. More engaging for a mature audience, perhaps, might be some of my other social encounters. When I was a member of the Nondescripts, the Christ Church sporting club, I recall attending a cocktail party hosted or attended by J. I. M. Stewart, the English literature don who had rooms on my staircase in Meadows 3. Now, not all of you may know that Stewart wrote detective novels under the name of Michael Innes, so I thought I would be very clever, showing off how familiar I was with his œuvre, and I thus asked him something about the plot of Landscape with Dead Dons. He paused, looked at me rather quizzically, and observed: “Forgive me if I am mistaken, but wasn’t that work written by Robert Robinson?”. I suddenly felt very small, and wanted to hide behind the sofa.

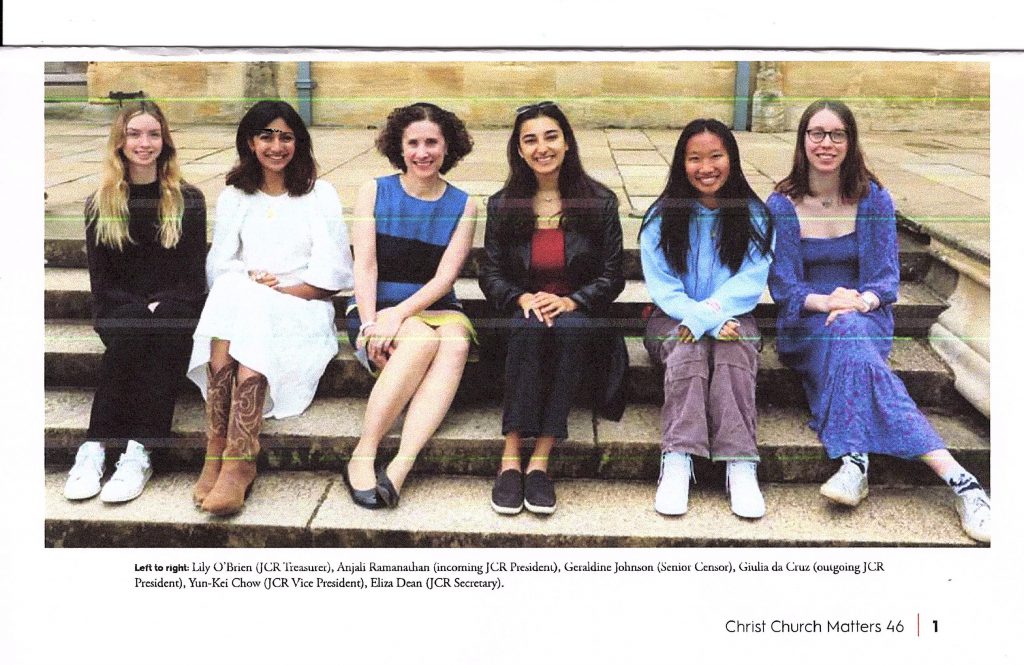

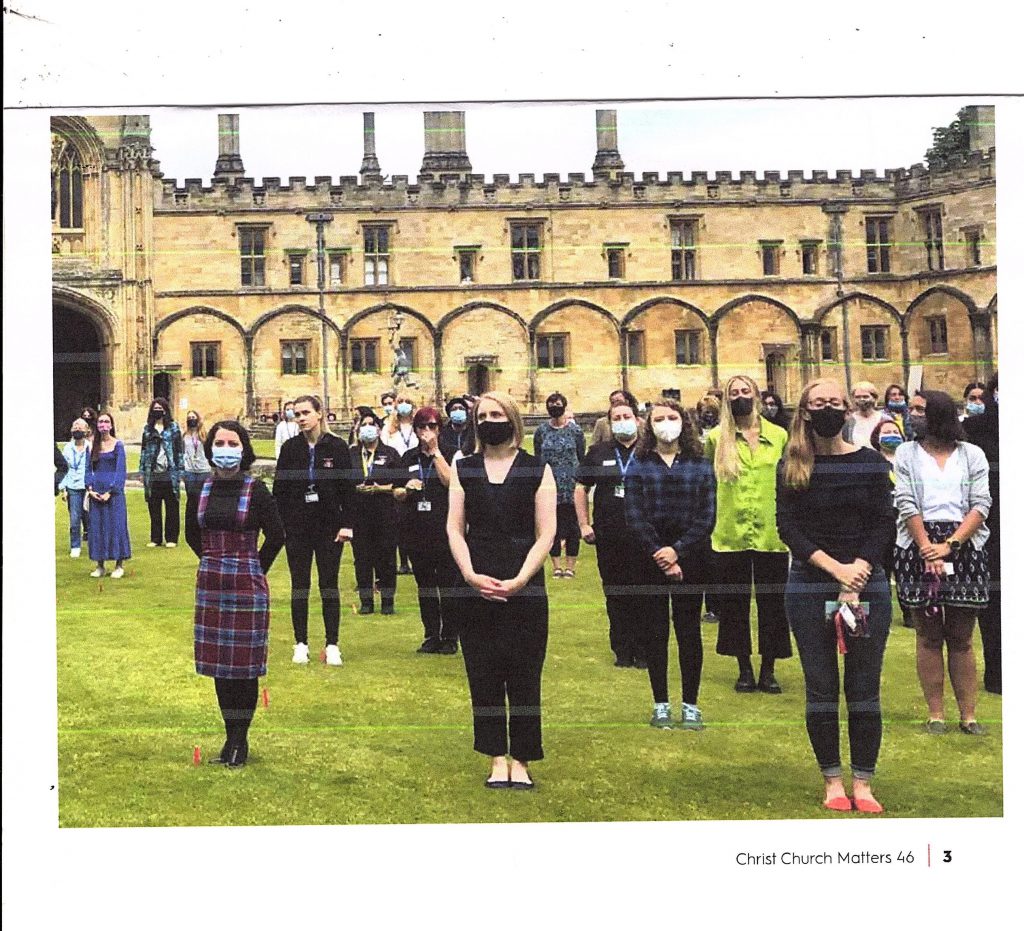

Now it has all changed. The latest issue of Christ Church Matters, received last month, celebrates ‘Forty Years of Women at the House’, and a wonderful milestone it is, indeed. The magazine is dedicated completely to women, with a very impressive Introduction by the Senior Censor, Professor Geraldine Johnson, who informs us that ‘Unlike Catherine Dammartin, whose corpse was temporarily buried in a dung heap in 1557 for daring to live within the confines of Christ Church despite being the wife of a Regius professor, today’s women know that they belong at the House, front and centre.’ And indeed they do, as all the little darlings [Is this usage wise? It sounds very patronising and 1970s . . . Ed.] can be seen in a wide range of glittering photographs, in their blue stockings, green sleeves, and black gowns, alongside the senior members of faculty, and all those in the Cathedral, Steward’s Office, Hall, Lodge, Library, etc. etc. who make the place hum. Completely unexpected in 1965, when I arrived and was matriculated.

And then came a passage to the real world: teacher training, with a term at Bognor Regis Comprehensive School (where I was sent on an emergency mission to teach Russian and German, since the previous incumbent had turned out to be far too energetic a rover with one of his pupils), and then a move away from academia to business, and IBM. After a while, I met my Greensleeves, as I have described in https://coldspur.com/my-experience-with-opioids/. It all started because, during my extended stay in hospital (four months, in fact), I saw the invitation outside the hospital window: ‘Please Help Our Nurses’ Home’, and somehow failed to notice the apostrophe. That was in the summer of 1973, and Sylvia and I were married in September of 1976.

1980-2021

We have lived more than half our lives in the United States, and nearly half of that period in Southport, North Carolina – far longer than I have ever lived in one place. My accent still seems to be a source of fascination to many, and I am accustomed to being asked by the check-out personnel in the supermarket, even when I have explained that I have lived here for twenty years: ‘Do you like it here?’.

In The Road to Little Dribbling Bill Bryson lists some of the features of his adopted country that he likes: Boxing Day; Country pubs; Saying ‘you’re the dog’s bollocks’ as an expression of endearment or admiration; Jam roly-poly with custard; Ordnance Survey maps; I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue; Cream teas; the 20p piece; June evenings, about 8 p.m.; Smelling the sea before you see it; Villages with ridiculous names like Shellow Bowels and Nether Wallop. I could quickly add a few from my own collection of favourite UK phenomena, namely Stonehenge; the Listener crossword puzzle; Promenade Concerts; Jeeves; sheepdog trials; clerihews and limericks; the Wisden cricketers’ almanack; the Bluebell Railway. Yet if I had to come up with a list of similar Americana, it would run: Thanksgiving, the Grand Canyon . . . and, er, that’s it.

Thus, while the USA has been an overall very positive experience for us, it does not contain many truly endearing features. And several things about the country and its habits and customs sometimes drive Sylvia and me to distraction. But, if they came to be really unbearable and unavoidable, we presumably would move elsewhere – but whither? In our seventies, an upheaval moving to some remote island, like my wife’s St. Vincent, or Maui, or Mauritius, or the Isle of Wight, does not seem very appealing It would be a hard adjustment: moreover, once you have kids who really have not lived anywhere else, and then the grandchildren arrive, that effectively seals the deal. So we live with all the oddities and frustrations of the USA, and its Bible Belt.

It is a droll irony that, while the Protestant Church in the United Kingdom is established (i.e. recognised as the official church, in law, and supported by civil authority), but the level of public unbelief is distinctly high, in the United States, there is supposed to be a constitutional separation between Church and State, while Christian fervour is an unavoidable presence in the public sphere. A few years ago, the local electricity company, Brunswick County Public Utilities, decided to have ‘In God We Trust’ inscribed on all its support vehicles. Lord knows how devolving everything to a deity would help in the reliable delivery of power to the local citizenry, and I found this an unnecessarily divisive and pointless initiative, at an unjustifiable expense. It was my Micro-Aggression of the month. (I was effectively told to clam up, and was referred to the minutes of the council meeting where the majority decision had been made.)

When we first moved to Southport, one of the first questions our neighbours asked us was: ‘What Church do you belong to?’, something that would still be considered horribly crass in the UK, I imagine, as what one’s friends believed in, or what they worshipped, was none of anyone’s business, but the interrogation seemed perfectly natural to Americans who did not even know us. I think they got the message when we held our first dinner party, and did not offer a prayer of ‘Grace’ before the meal, a ceremony that can be seen quite frequently in public restaurants, with participants holding hands around the table. In Brunswick County can be found churches of practically every conceivable Christian denomination: Pentecostal, Evangelical, Baptist, Lutheran, Quaker, Methodist, Presbyterian, Reformed, Unitarian, Mormon, Apostolic, African Methodist Episcopal, Catholic, as well as Jehovah’s Witnesses and Christian Scientists. I have no idea what doctrinal differences separate these institutions, and have no wish to find out.

We attended the memorial service for a neighbour at the Episcopal Church in Southport a few months ago. I was astonished at how high-church it was. Swinging censers, the ritual of the eucharist, and the congregation all declaiming earnestly their belief in the Apostles’ Creed, and especially Eternal Life. When obituaries in the local paper state that the deceased (who normally has not ’died’, but ’passed’) has ‘gone to be with Jesus’, or ‘taken by the angels’, those who mourn him or her mean it quite literally. The after-life is ‘a better place’. But I can’t help but feel that if such people accepted that this life on earth is the only one they are going to have, they might value it rather more than they do. Ascribing disasters and premature or avoidable deaths to ‘God’s will’, or to His ‘Plan’, in the belief that everything will be well when we are all re-united, is a deeply depressing philosophy, in my opinion. It suggests that life is merely some dire metaphysical project akin to the Communist Experiment. And it is also a little hypocritical. When survivors of a tornado are pulled from the wreckage of their houses, their first statement is frequently: ‘The Lord saved me’, the implication being that the person down the street who did not survive was unworthy of such grace.

And yet. The charity . . . . The organisation of food-pantries when disasters like tornadoes and hurricanes strike . . . The helping hands offered to neighbours and strangers. All very splendid and admirable, but not a little perplexing.

Someone (Meister Eckhart, C. S. Lewis, Teilhard de Chardin, Cardinal Newman?) once said that one believes in this rigmarole purely because it is utterly irrational and inexplicable, which seems to me an argument for anything, like believing in the Tooth Fairy. And that line can take you into the Paul Johnson school of theology, namely that ‘because Christianity inspired great art, it must be true’. What is astonishing to me is that if otherwise smart persons are taken in by such nonsense, are they not likely to be taken in by a lot of other absurd theories that circulate – especially on the Web? Why should the particular mythology that was instilled into them at primary school have any greater significance and durability than any other? And what happens – heaven forbid! – when politicians take some disastrous course of action to which they say they were divinely inspired? Or fundamentalist Christians (or those claiming to be so) resort to quoting the Bible to avoid having to be vaccinated against Covid-19?

As I was putting the finishing touches to this piece I read, in the New York Times, an obituary of John Shelby Spong, a bishop in the Episcopal Church. He was born in Charlotte, North Carolina, in 1931. His mother was a strict Calvinist ‘who refused to sing hymns because they were not the word of God’, and it was apparently such fundamentalism that prompted Spong’s subsequent rejection of Christian orthodoxy. Thus Spong called on his flock to reject ‘sacrosanct ideas like Jesus’ virgin birth’ (no questions of womb-abhorrence for Spong, then) and ‘the existence of heaven and hell’, and in 2013 he preached that several of the apostles were ‘mythological’, also claiming that the notion that Jesus’ blood had washed away the sins of Christians was ‘barbaric theology’. But why stop there? If you start dismantling the whole edifice as superstition, there will not be much left. I was not surprised to read that the Bishop of Brisbane had barred Spong from speaking in his diocese.

God granted episcopant Spong

A life that was wondrously long;

This in spite of the breach

When Spong started to preach

“What the Bible reveals is all Wrong!”

Still, not much else I can do about it all, especially if some insiders have woken up to the truth. And it is not as if we atheists get together in pressure-groups, or go on marches. No point in having meetings to discuss policy: “Still no God, then?”; “So who brought the donuts?”; “Same time next month?”. I do occasionally venture out into the public sphere, however. Several years ago, the local paper printed a letter from a local citizen who had become angered that Walmart had replaced its ‘Happy Christmas’ welcome sign with one saying ‘Happy Holidays’. I was moved to respond, and the State Port Pilot published my letter, which ran as follows:

May I respond to Mr Livingston’s letter (‘Xmas’) with a few anecdotes?

In the country where I was born, the UK, where there remains an established church, the religious aspects of the Christmas festival had long been melded with pagan traditions. And to me, the beautiful Festival of the Nine Lessons and Carols, from King’s College, Cambridge, was as much a cultural event as a religious ceremony. Thirty years ago, there was no awkwardness about calling the period ’Christmas’, although today the members of the European Union are divided as to the degree to which they should acknowledge their Christian heritage.

When I came to the US, in 1980, I was quickly reminded how socially inept it was to send a Christmas card to friends who were Jewish, no matter how loosely religious they were. And a few years later, the new (Jewish) wife of an old friend of mine stormed out of the room when I – a non-believer ̶ put on some ‘Christmas’ music. (And it wasn’t Grandma Got Run Over By A Reindeer). But how was I supposed to know? And wasn’t that a bit of an overreaction?

When I came to Southport a few years ago, I was astonished that a Christian prayer was said at a secular business meeting, and I am still surprised that your columnists refer to ‘our Lord’, as if the Pilot were a parish magazine. But it does not surprise me that Walmart should have decided that it wanted to post a message of seasonal goodwill to all its customers, whether they be Jews, Sikhs, Moslems, Buddhists – or even atheists – as well as the dominant sects of Christianity. Mr Livingston can continue to enjoy making his personal celebrations in his church.

Finally, Happy Holidays to you and all your readers!

In conclusion, this extended anecdote is really a celebration: I did not find God, but I found my Greensleeves. I look back on my life of almost seventy-five years, with many important decisions made and a good number of lucky breaks accepted, of which meeting Sylvia was the best. My thanks to my beautiful and adorable wife for supporting me for so long.

Greensleeves was my delight,

Greensleeves my heart of gold

Greensleeves was my heart of joy

And who but my lady Greensleeves.

(This month’s Commonplace entries can be seen here.)

Purley. Not Purely, Percy!

Freudian?

David Scothorn. (Oxon)

It was a joy to read your tome even though I had to use unabridged dictionary to decipher some of your words. You and I long ago discovered we were on the same page about many of the issues you raised. You should do more of these pieces and expanded, there is a book. Thanks for sharing.

Regards,

Tommy

T