Introduction

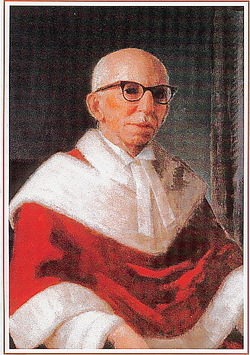

In my May report on ELLI, I set out to make the case that a group of intelligence officers, primarily in MI5, had attempted to frame Roger Hollis as the mysterious spy whose cryptonym was revealed by the defector from Soviet Military Intelligence (the GRU), Igor Gouzenko. I did not explore why they did this – a detailed analysis is a subject for another day. In brief, it was a convenient cover for MI5’s general indolence over the ELLI business, and its failure to put the matter to bed. To have a cloud hanging over Hollis (one that not even Burke Trend in his careful investigation could dispel) provided them with a scapegoat, and an explanation for all those failings that had reportedly damaged MI5’s performance in Soviet counter-espionage. At the same time, apart from the fanatics like Peter Wright and Arthur Martin, most officers probably believed that Hollis was innocent, not being ready to credit him with the brains and wiles to deceive his colleagues so ably. (And even Arthur Martin recanted in his old age.) Yet Chapman Pincher’s vigorous claims about Hollis’s guilt have dominated public perceptions.

Another dimension of the case fit for exploration is that list of intelligence failures which led Wright and his colleagues to assume that MI5 had been betrayed by an insider, a catalogue written up in Wright’s Spycatcher, and in Nigel West’s Molehunt. Again, an inspection of how real these failures were, and whether they should have been justly ascribed primarily to high-level leakages, will have to wait for treatment another time. But a third dimension is what occupies my research this month – the testimony of Igor Gouzenko. How could it be that the presumably straightforward evidence he gave of ELLI’s activity has been so miscommunicated, distorted, denied, overlooked, even concealed? I decided that a stricter investigation into what he said to various persons and agencies was merited, as an attempt to shed light on the rather bewildering behaviour of those who should have been processing his disclosures.

I shall not dwell here on Gouzenko’s character. He was by most accounts a difficult man, greedy, obstinate, peevish, litigious, and ill-mannered. While he impressed his interlocutors in Ottawa with his memory and clarity of thinking, his articulation was once described during earlier interrogations as incoherent. Irrespective of his personal faults, however, he displayed a willful contrariness in his testimony over the years, and it is hard to ascribe his inconsistences simply to a failing memory, or to the much-questioned fact of his alcoholism. For my own purposes, I knew I needed to apply a strict chronology to his statements, so that I could more easily cross-refer those assertions that collided. And that is what this report consists of.

This is not an easy read – one perhaps for the aficionados only. (Casual readers may wish to skip to the Conclusions after reading ‘Statements and Confessions’ below.) The construction of the report has helped crystallise my thinking, however, and I believe that the piece will constitute an important resource for any other historian/researcher who wants to investigate the bizarre ELLI phenomenon, and to shed further light on it. (And if I have missed any relevant Gouzenko statements, please let me know.)

Statements and Confessions

In their attempts to prosecute spies, MI5 and the Department of Public Prosecutions have always relied heavily on confessions. The prevailing methods of gaining evidence (telephone surveillance, or transcripts of intercepted hostile communications) were considered too secret to be used in court, and would probably have been dismissed anyway as being too vague and circumstantial. Thus, apart from catching the suspect red-handed in the act of passing over documents to his or her controller (as Special Branch hoped to trap Nunn May), the spy had to be persuaded to make a confession.

Yet even that process was problematic. Klaus Fuchs was inveigled into making a statement to Bill Skardon, and it represented the primary evidence in his trial. MI5 knew, however, that it was probably compromised by the fact that it had been offered under duress, as some sort of quid pro quo. Fuchs’s lawyer was not canny enough (or had been guided otherwise) to show that the statement was thus tainted, and the case was quickly concluded. Or the process could be more fortuitous. George Blake was so offended by the suggestion that he had spied for the Reds for mercenary reasons that he blurted out that his espionage had been performed out of ideological purity.

The UK authorities were normally less eager to prosecute homegrown spies (apart from Nunn May), a public trial threatening to become a total embarrassment. Thus, with the Cambridge Five, seeking a confession was more a method of clearing the books, and trading an apology for facts, in the hope that the lack of publicity would allow the whole story to be buried. Yet MI5 counter-intelligence officers and Civil Service mandarins displayed an enormous amount of naivety in so doing. They dithered over interrogating Donald Maclean (who might well have succumbed, given his psychological state), allowing him to escape with Burgess. They gained a minimal confession from Cairncross at first, and banished him from government employment. Nicholas Elliott extracted a weaselly confession from Philby in Beirut, but Philby absconded immediately afterwards. Blunt was offered a pardon on the basis that he would make a full confession, and would also confirm to his interrogators that he had not spied since the end of the war [!]. He obliged, but lied in so doing, and his confession was by no means ‘full’. At the second take, Cairncross gave a fuller confession, but it was on American soil, and thus not valid evidence in an English court. Moreover, he declined to repeat it after being given the requisite legal warning.

With defectors, one might expect the business to be cut and dried. After all, they were volunteering information, and their intentions were presumably friendly. The process of interrogation should have been leisurely, and the ability of their questioners to verify the story should have been explicit. One might thus assume that signed statements would become an integral part of the data collection exercise. Yet this phenomenon also had its problems – concerning language, fear, accessibility, and trustworthiness.

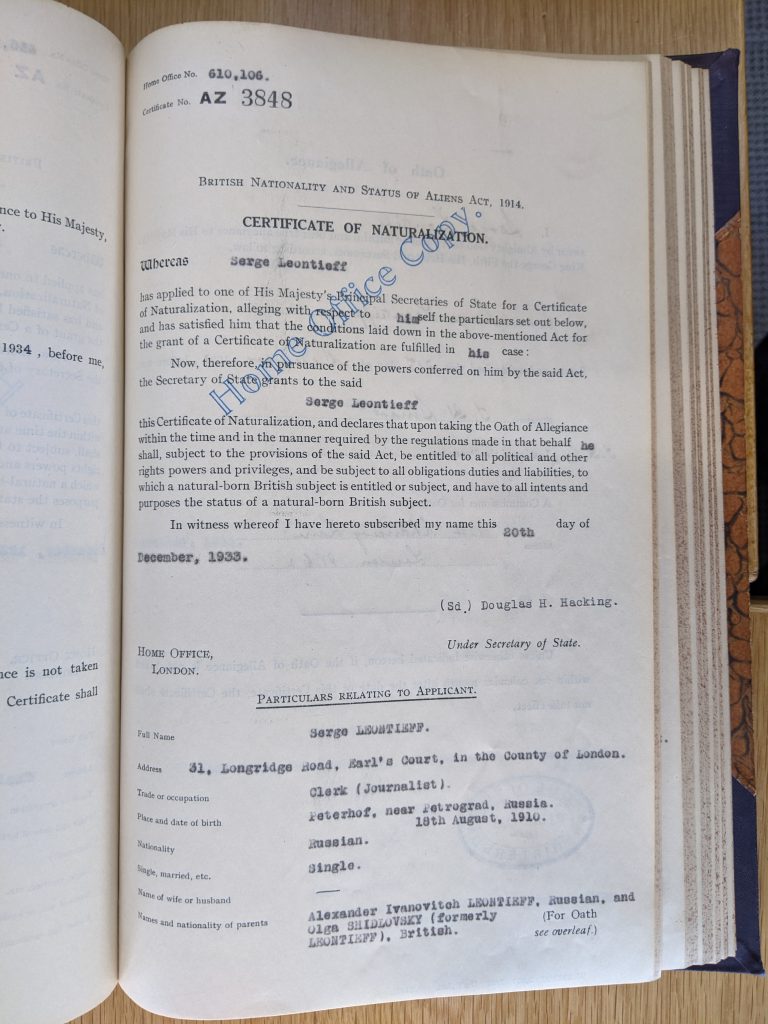

The closest analog to Gouzenko’s situation is probably that of Walter Krivitsky. After receiving the fatal message of recall to Moscow, Krivitsky abandoned his position with the GRU, escaped from France to the United States, and was then marooned in Canada. He agreed to come to the UK to be interrogated, because he might have needed favours in order to gain a residence permit. Having arrived in January 1940, he was cloistered in a hotel for over three weeks, where he was interrogated primarily by Major Alley, a Russian speaker, and Kathleen (Jane) Archer, MI5’s expert on Soviet intelligence. He was initially nervous, but Archer gained his confidence. Krivitsky, while virulently anti-Stalin, was however still a Communist. He did not want to betray any personal colleagues, and he did not want to make MI5’s job too easy. He spoke only a little English.

The outcome was that Archer was able to compile from Krivitsky’s testimony a lengthy and authoritative report on Stalin’s policies, and the organisation of Soviet intelligence. Krivitsky had already published revealing articles in the USA, so he knew he was a marked man, but here he was able to provide more targeted hints at the nature of Soviet espionage against Britain. Yet he never signed off on the report, which was compiled after he left. The discussions proceeded rather haphazardly, and probably according to Krivitsky’s whims. As Archer wrote: “The facts and views expressed are put down as nearly as possible as told by him. The work represents an attempt to sort out and put into coherent form a mass of information gleaned from KRIVITSKY at odd moments in the course of lengthy and diffuse conversations extending over three or four weeks.” Nothing was tape-recorded. Later attempts to contact Krivitsky to clarify points failed. He was murdered in Washington in February 1941.

The bulk of Igor Gouzenko’s overall testimony was diligently recorded, as the Canadian Government set up a commission to investigate the circumstances of his defection, and the details of the spy-ring he uncovered, but his evidence about Soviet espionage in Britain was more problematic. Even though he was bitterly opposed to the whole Communist system, and thus sincere in wanting to reveal all he knew, he was highly suspicious – because he believed all government institutions might have been infiltrated by Stalin’s agents. Moreover, what he had to reveal about the UK was primarily information gained at second-hand – and the Canadian government warned him about not disclosing ‘hearsay’ evidence as factual. His spoken English was also poor (although the demonstration of that fact is ambiguous), and his early interrogations suffered from a highly undisciplined approach by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), which was unpractised in such matters. Hence the regrettable muddle about exactly what he said, when, and how reliable such statements were. It is for that reason that my task here is to report and analyse closely everything that Gouzenko was reputed to have said or written about the mysterious figure known as ‘ELLI’.

I thus concentrate here not on the broader material on the organisation of the GRU, and the profiles of its agents in Canada, provided by Gouzenko, and thoroughly documented, but solely the scattered comments he made on Soviet penetration of British Intelligence in London. I identify these (including some events that may be purely apocryphal) individually as follows:

Summary of Gouzenko’s Statements

- Informal statements to the RCMP, communicated by Dwyer in daily reports (early and mid-September, 1945)

- The so-called ‘BSC Report’ (September 15 et al.)

- The ZILONE telegram (October 16)

- The statement in late October

- The interrogation on October 29

- Re-interrogation and cables in early November

- The interview by Roger Hollis on November 21

- The RCMP Report (November)

- The testimony to the Commission (February, 1946)

- The interview by Guy Liddell (March 20)

- A possible second interview by Hollis (May 23)

- Commentary on the Hollis report (November 1946)

- Statements in Gouzenko’s Autobiography (1948)

- Ann Last’s Notebook (1950)

- The statement to the RCMP in 1952

- The memorandum from the FBI (October 1952)

- Senator Jenner’s sub-committee (January 1954)

- The response to Stewart in 1972

- Communications with Chapman Pincher

1. Informal Statements to the RCMP:

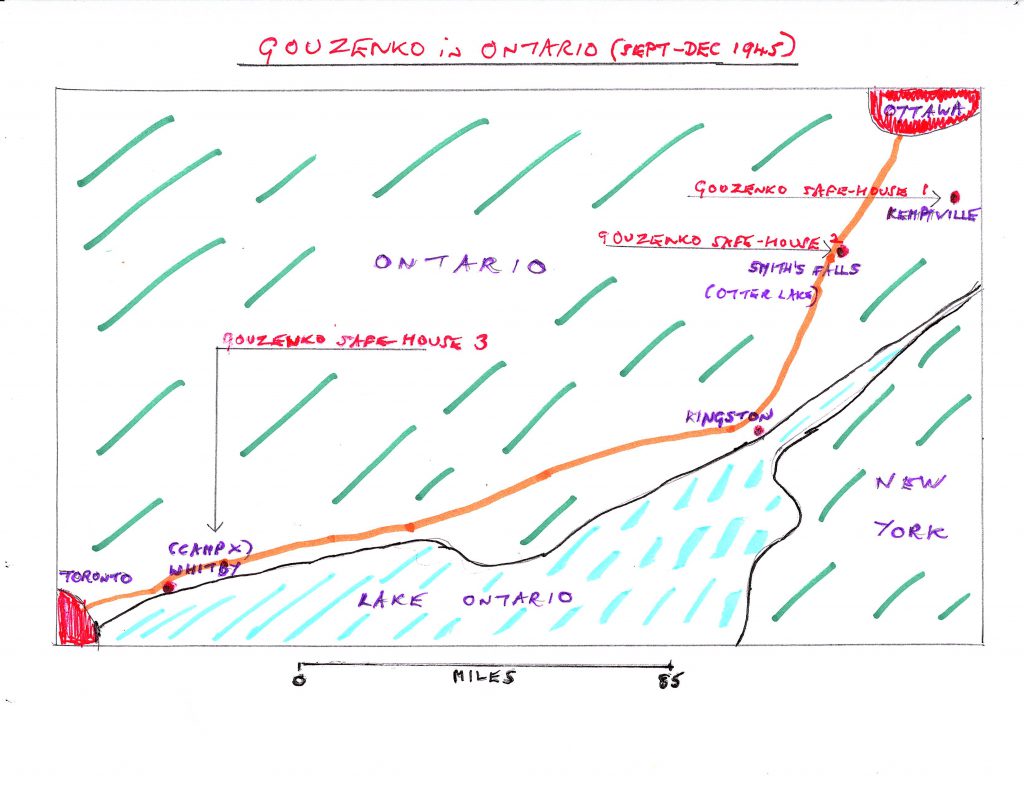

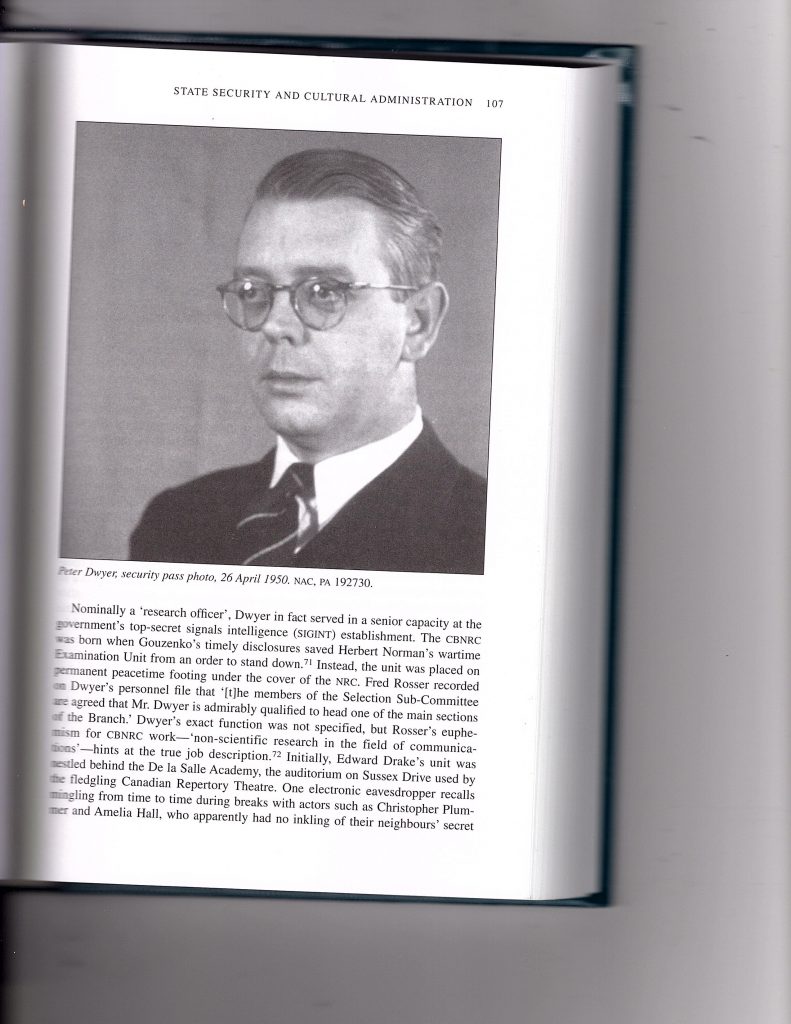

Officers of the RCMP began interrogating Gouzenko, and then releasing the information they learned to Peter Dwyer (of MI6 and BSC) and his colleague John-Paul Evans, immediately he was moved to his first safe house, probably around September 10, 1945. Dwyer then began sending daily bulletins back to Kim Philby in MI6. The RCMP was not very well organized. According to the officer John Batza, John Leopold (whose Russian was not very good) started interviewing Gouzenko in the first cabin in which he and his wife were installed, at Kemptville. Evans and Dwyer did not question Gouzenko themselves, a fact confirmed by Evans. In a letter to David Stafford (the author of Camp X) Evans wrote that Leopold was the only direct contact with Gouzenko. “He would spend some time with him each day, going over the translations which he would have made to date and questioning him as required. He would bring the material to me and I would write it up and raise queries as they arose. Peter would also study the results and generally deal with matters of liaison.” This procedure was not ideal, but at least suggested an attempt to verify facts. Thus the early signals that Guy Liddell and co. received about ‘ELLI’ originated in less than perfect surroundings, but should have resulted in greater precision.

The only mention of ELLI in this period is the statement in Guy Liddell’s cable of September 23: “Reference your CXG 301 of 13.9.45 – do not consider that ELLI could be identical with UREN.” So what can one draw from this, given that the cable of September 13 has not been released? Gouzenko certainly did not know about SOE, the Special Operations Executive, where Ormond Uren had served. Dwyer assuredly knew that Uren had been convicted for espionage, but his suggestions that Uren was ELLI might have been a wild stab, the statement that he was working on not necessarily including any reference to SOE, or connections with Moscow.

Yet Liddell quickly dismissed Uren’s candidature, while not rejecting the SOE link. Gouzenko and Dwyer must have passed on additional information that did more than claim that a spy was at large in British Intelligence. It is more likely that the hints provided enough of a clue that indicated to Liddell (any maybe Dwyer) a link between ELLI and SOE, rather than between him and MI5 or MI6. That can only have been because of knowledge of the presence of the SOE station in Moscow, and it would thus point to the fact that Gouzenko had made a claim about the existence in 1942 of a British Intelligence spy in the Kremlin. Liddell’s familiarity with George Hill’s set-up in Moscow, alongside his awareness of Uren’s conviction for espionage, must have suggested to him that Uren was at least a plausible explanation. As I wrote in May: “Something in the information provided by Gouzenko must have indicated to him either a) that there were corners of SOE’s organisation that were not known to Uren, or b) that the disclosures had occurred either before his recruitment to SOE (in 1942) or after his arrest (in July 1943), or c) that the additional hints about ‘Russian descent’ excluded Uren. The third alternative seems the most likely, and may have pointed him towards Alley. In addition, Uren was known to have worked by supplying secrets to Dave Springhall, not to a Soviet handler from the Embassy.”

2. The BSC Report:

This item was not a singular document, but something that was regularly amended after its first publication, and it reflected the evolving story as described by Gouzenko. (BSC was British Security Coordination, the wartime intelligence organisation set up in New York under Bill Stephenson.) Amy Knight (p 60) presents it in the following terms: “ . . . the British had put together a comprehensive report on behalf of the BSC, entitled “Intelligence Department of the Red Army in Moscow and Ottawa, 1945”, and she sources it as C293177 in the CSIS (Canadian Security Intelligence Service) files on Gouzenko. For clarification, she adds that ‘the report listed twenty-seven individuals who were connected with Zabotin’s GRU network in Canada, including an American scientist named Arthur Steinberg.’

While this document has not been released, it would appear to be in essence the same as the document residing in the Gouzenko file at the National Archives, in KV 2/1420. Titled ‘THE CORBY CASE’, it is introduced by verbiage (dated 25.9.45) that explains that the following pages should be interleaved or substituted into the preliminary report. The dates of the inserts range from September 13 to October 7, and this Issue Number 3 was posted on October 30. It does indeed include a reference to Steinberg, but, as with many other sections, it has been redacted, and no information about him is visible. Since Knight is able to quote Dwyer’s and Evans’s comments on Steinberg, presumably from the Canadian version, it seems odd that this information had to be redacted when the copy was stored in the UK.

It is page 30 of the British version of this report that contains a reference to ELLI, as described by William Tyrer in his article ‘The Unresolved Mystery of ELLI’, where he describes the report as ‘the long report from the RCMP’ (thus a source of some confusion). The whole page has been removed, but ELLI’s substance is confirmed by the Alphabetical Index of Cover Names, where ELLI is differentiated from ELLIE (Kay Willsher) as ‘Unidentified agent in England in 1943’. This would appear to offer adequate proof that Gouzenko had provided tangible evidence about the mysterious spy. That certain names were too sensitive to be displayed is confirmed by two cables from New York, dated September 14 (Sns. 11A & 12A of KV 2/1420-2), which list by alphabetic letter a summary of station agents, from A to S (who happens to be STEINBERG). Items M & N have been redacted, but it is not clear who has been omitted, as this is a very preliminary list, and the cable concludes: ‘Name of further individuals to be uncovered shortly.’

Tyrer was nevertheless able to extract an important item from the Canadian archive dating from this period, and it makes sense to include it as part of ‘The BSC Report’, since it is this testimony to which the Index entry must surely relate. Tyrer assumes that this document (given as C293235 in MG26 J4, Vol 417, Library and Archives Canada) is the same as the item removed from the BSC Report, and I am sure he is right. His quoted text runs as follows:

Alleged Agent in British Intelligence

Corby [the codename for Gouzenko] states that while he was in the Central Code Section [in Moscow] in 1942 or 1943, he heard about a Soviet agent in England, allegedly a member of the British Intelligence Service. This agent, who was of Russian descent, had reported that the British had a very important agent of their own in the Soviet Union, who was apparently being run by someone in Moscow. The latter refused to disclose his agent’s identity even to his headquarters in London. When this message arrived it was received by a Lt. Col. Polakova who, in view of its importance, immediately got in touch with Stalin himself by telephone.

I presented this, as quoted by Amy Knight, in my May coldspur bulletin (while drawing attention to her misattribution of the occasion as Hollis’s non-existent interrogation of Gouzenko in September), and, indeed, she gives page 30 as the source, thus confirming the equivalence, and showing that the fuller text in the Canadian archive compensates for the redacted version in the British archives. The timing of the communication of this nugget would appear to confirm also that this is the item that excited Dwyer/Evans and Liddell, and started them on the trail of hypothesizing about SOE and the station in Moscow. KV 2/1420 informs us that Sergeant Bayfield of the RCMP probably brought the original version of this report straight to Menzies on September 16. Roger Hollis brought with him updates to it when he returned to the UK on September 28.

3. The ZILONE telegram:

As I reported in March, the Gouzenko archive (KV 2/1421, s.n. 35a) shows a cryptic and incomplete reference, dated October 16, in Telegram No 533, sent with some urgency (‘MOST IMMEDIATE’). Its text runs as follows:

A. CORBY states that cover name for ?all foreign ?intelligence or counter espionage services is ZILONE repeat ZILONE meaning green in Russian.

B. Agent referred to by CORBY in 534 was referred to as working in ZILONE.

So why was the revelation that the agent that Gouzenko had identified worked in counterintelligence suddenly that urgent? Had that fact not been communicated in September? ZILONE could presumably refer to either MI5 or MI6 – but also to SOE, since the Soviets made no distinction between SOE and MI6 (as this telegram confirms), which may have been significant. It might seem that someone in London had raised a question, and that Gouzenko wanted to clarify that his ‘Central Code Section’ handled traffic from all British intelligence services.

4. The Statement in Late October:

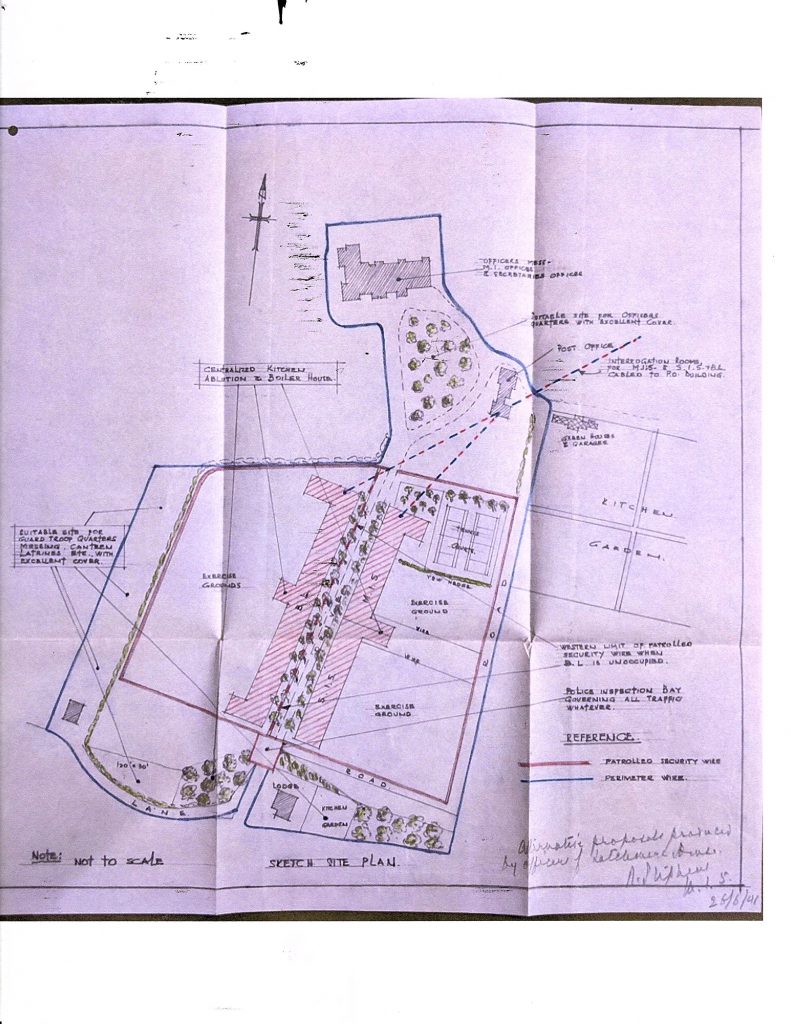

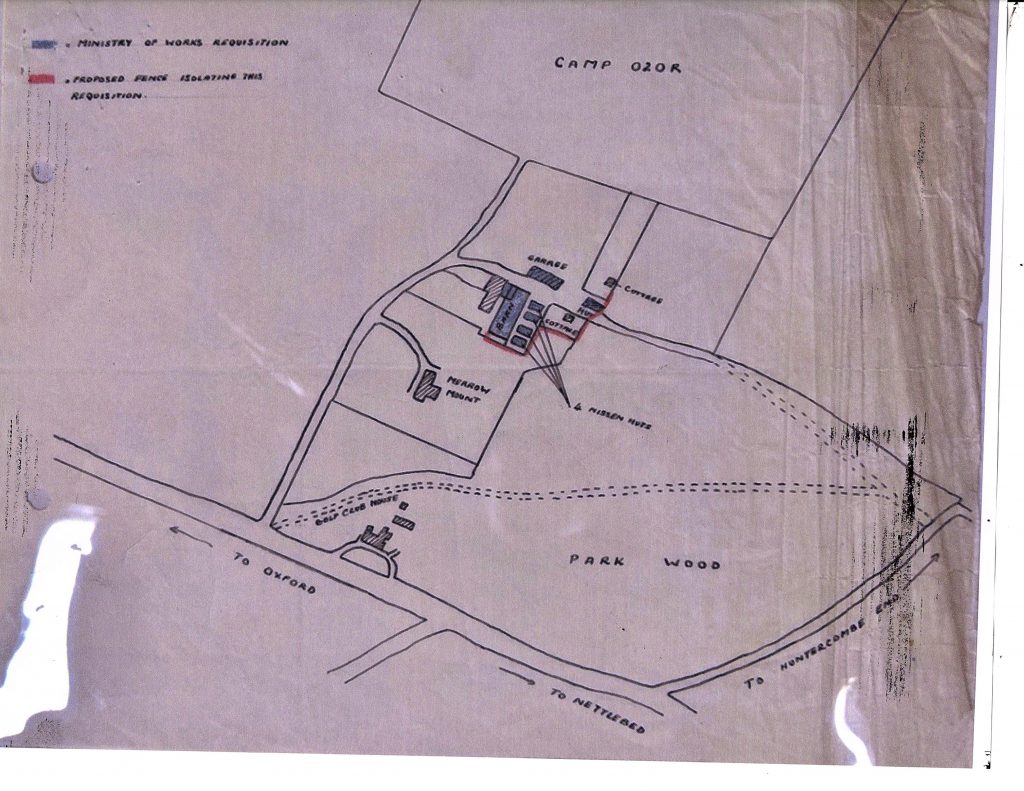

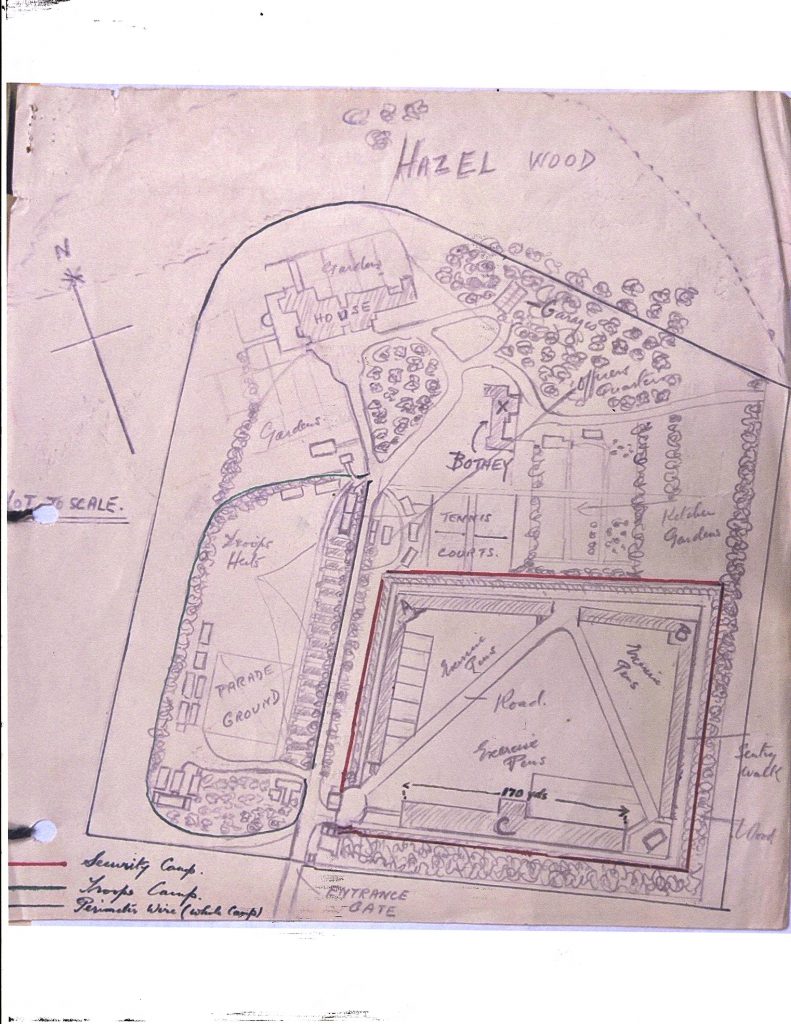

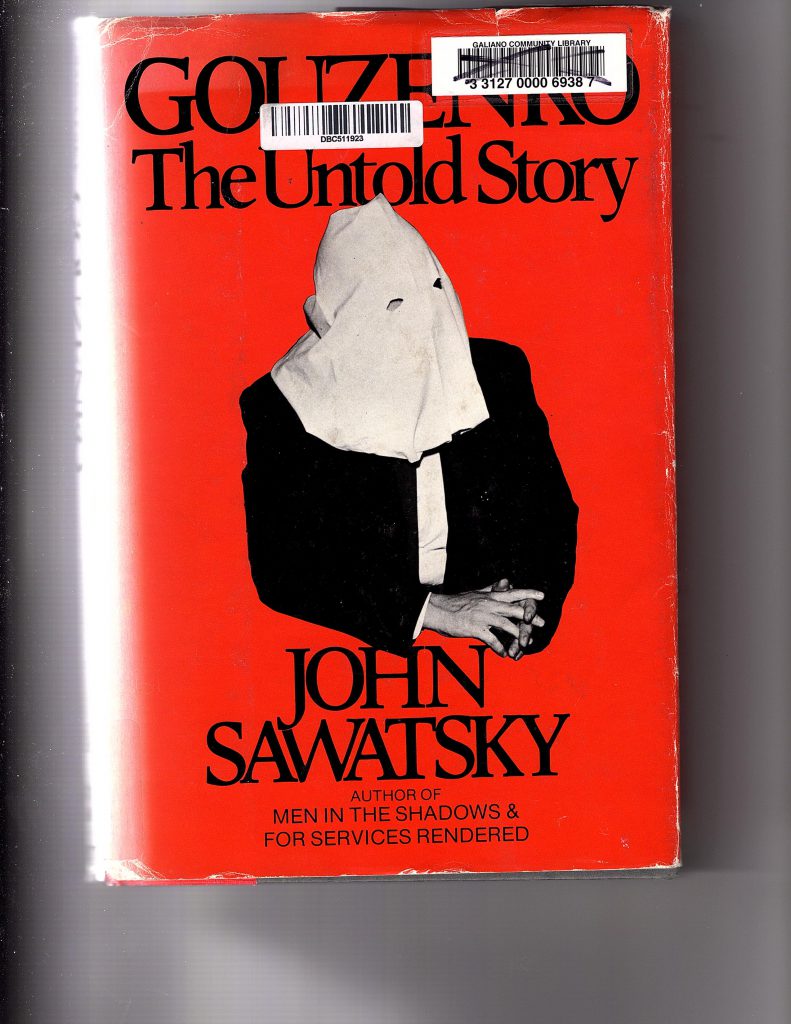

In early October, the Gouzenkos were moved to Smith’s Falls, to a place on Otter Lake, and here, according to one report, a more competent translator, Mervyn Black (who was born of Scottish parents in Petrograd), was introduced. Soon after that, a more permanent accommodation was found, much nearer Toronto, in a farmhouse at the Camp X establishment, which was an SOE training facility, and communications centre. The testimony provided in Gouzenko: The Untold Story, the compilation by John Sawatsky, is unfortunately not very reliable. George Mackay, another RCMP officer, claimed that Gouzenko, shortly after he and his wife arrived, ‘was being interviewed by various people in the Mounted Police and some MI5 people’. (He presumably meant ‘MI6’ or ‘BSC’, but his evidence is the only testimony that suggests non-RCMP personnel were allowed to visit.) Moreover, despite the seclusion, and the availability of more appropriate buildings nearby, the method of interrogation was still crude. Another RCMP officer, Don Fast, contributed that ‘a lot of the debriefings took place in the car’, as the authorities ‘were trying to get him away from the noise and the child and whatnot.’

On the other hand, Svetlana Gouzenko remarked that Leopold was still active on the interrogation team at Camp X, but continuing to struggle, misunderstanding what her husband said, and constructing organisation charts that were ‘wrong’. She indicated that, on one occasion, ‘six or seven of them [RCMP officers] would be all downstairs at this big farm table and they would be sitting there’, adding that ‘each of them would look for some point that he wanted clarified’. It sounds all very chaotic, especially as Gouzenko did not trust the RCMP.

Another account suggests that Black was involved by then as chief interpreter. Amy Knight cites a letter from the CSIS files, dated October 11, when Inspector George McLellan of the RCMP wrote to Rivett-Carnac in Ottawa: “I would like to point out that under the present conditions at Rexall [Camp X] at the moment, Black laboured under much difficulty in obtaining the statement already submitted herewith, and it will take some days to get a complete statement in the manner in which you want it. This is due to the fact that Corby has somewhat of a dreamer mentality and it is extremely difficult to pin him down to the business at hand.” Such observations anticipate the frustrations later expressed by Liddell over the lack of coherence in Gouzenko’s evidence.

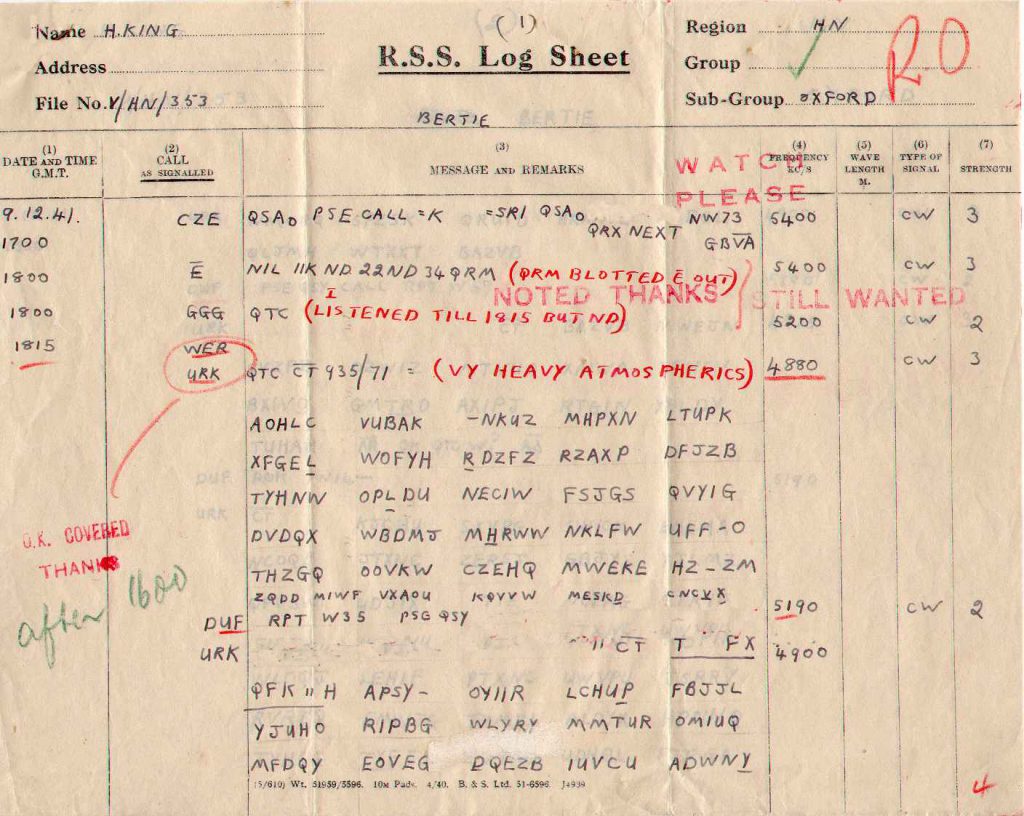

Guy Liddell reports a further bulletin from Gouzenko during this period. His diary entry for October 24 (also recorded by Tyrer) runs as follows:

John Marriott showed me a new wire which has come in from the other side indicating that the CORBY case is breaking. Warnings have obviously been given to a number of people. There is also a further telegram about the agent known as ELLI who is alleged to hold some high position in British intelligence. References are made to C.E. [counter-intelligence] but as CORBY’s theories are only based on scraps of information picked up here and there there is not much to work on. It is possible in mentioning the figure 5 he is referring to the five people who formerly signed JIC reports. It equally does not follow that because information is high-grade it comes from a highly-placed officer. It may mean that an extra copy of JIC reports is coming off the roneo and being passed by a clerk. In this connection the KING case is not a bad illustration. Hooper always referred to Vansittart as the source of the information and we found afterwards that his name was only used to cover up the high-grade reports received from cypher communications which KING was handing out to the Russians.

Tyrer reports that this telegram (and the following one) were sent ‘during Hollis’s second visit to Canada’, as if implying that his presence had something to do with the distribution, but that cannot be true. This cable was probably sent – and arrived via Philby – before Hollis left. Hollis did not depart until October 22, sailing from Southampton for Halifax on the Queen Elizabeth, and thus would not have arrived in Ottawa until several days later. His first report from there (concerning Nunn May) appears to have been sent on October 31. In any case, Hollis soon moved to Washington for meetings between Attlee and Truman, and a note from Petrie indicates that he wanted Hollis to stay there until November 18. Indeed, on November 19, Hollis reported a meeting with Edgar Hoover, chief of the FBI. The RCMP, however, pressed for him to return to Ottawa before he took his seat on the Clipper on November 26 to return to the UK.

The cable itself has not been released, so we are left puzzling over that first enigmatic reference to ‘the figure 5’, and what it meant. One of the ‘Cambridge Five’? – I do not think that that interpretation has been considered. In any case, the attitude of Liddell seems extremely blasé, even irresponsible. Even if the spy were not as ‘high-grade’ as the information supplied, that was no reason for complacency. The KING case had alerted MI5 to gross lapses in security at the Foreign Office, and here was possible evidence that similar poor practices were in use at one of the intelligence agencies.

5. The Interrogation on October 29:

Knight draws attention to the next incident, an interrogation that took place on October 29, recorded only in handwritten notes, and sources it as ‘Transcript 000009, interview 2, October 29’. It is possible that Gouzenko returned to Ottawa for this briefing, but the fact that the notes were only hand-written suggests that the interrogation was less formal. There again, the evidence from the RCMP officers is unreliable. In Gouzenko: The Untold Story (where dates are almost completely absent), Herb Spanton states that he took Johnny Leopold to Camp X, where he met [sic] Gouzenko, suggesting that he had not encountered him before – a claim that contradicts what Batza had earlier stated about Leopold’s acting as translator at Kemptville (see above). Spanton added that ‘the next day we left for Ottawa [a journey of about 250 miles] and Igor came with us, but he wouldn’t ride in the same car as Leopold.’ As far as Gouzenko was concerned, Leopold was a spy. Yet The Gouzenko Transcripts present Leopold as ‘close to an expert on communism and the Soviet Union as the R.C.M.P. possessed’. (p 155)

Be that as it may, Gouzenko provided further clues about ELLI during this interrogation. Apparently he said that it was

. . . possible that he or she is identical with the agent with a Russian background who Kulakoff [Kulakov, Gouzenko’s successor, who had recently come from Moscow] spoke of – there could be 2 agents concerned in this matter. CORBY handled telegrams submitted by ELLI . . . ELLI could not give the name of the [British] agent in Moscow because of security reasons. ELLI [was]already working as an agent when CORBY took up his duties in Moscow in May 1942 and was still working when Kulakoff arrived in Canada in May 1945. Kulakov said agent with a Russian connection held a high position. CORBY from decoding messages said ELLI had access to exclusive info.

The most remarkable aspect of this item, for me, is the twice-told statement that Gouzenko himself was responsible for ‘handling’ and ‘decoding’ messages from ELLI. The verifiability of this activity will have serious implications as the story progresses. What also stands out is the suggestion that telegrams were ‘submitted by ELLI’. That cannot be right, as ELLI would not have direct access to Embassy cable resources. Messages from ELLI would have been packaged by his or her controller. This must be an error of understanding/translation. The fresh revelations from Kulakov concerning the spy’s still being active in 1945 would dispel any lingering illusions about Uren.

6. Re-interrogation and cables in early November:

Guy Liddell’s next diary entry on ELLI appears dated November 5. One might assume that it refers to the interrogation of October 29. It runs, however, as follows:

Marriott showed me some recent telegrams on the subject of ELLI. CORBY has been re-interrogated and refers to an incident where the Soviet M.A. in London referred to information that he had received from ELLI relating to a British agent in Russia. As the only organisations that can possibly have been running a British agent in Russia were SIS, SOE or the British Military Mission, it seems unlikely that ELLI could have any connection with ourselves. Nobody in fact knows anything about any agent in Russia. I should doubt very much whether there was one. The above does not necessarily throw any doubts on the bona fides of CORBY, who may have got the story wrong.

This entry is noteworthy for several reasons. (As Tyrer notes, Liddell’s comments are ‘perplexing’.) First, it refers to ‘some recent telegrams’, suggesting three or four, at least. None has been released to the archive. Given the delay in channelling the messages through Philby, and the traditional lag time shown in Liddell’s previous reactions, one might assume that the interrogations referred to antedated the events of October 29. Indeed, Liddell does not refer specifically to the news imparted in the previous item: one might have expected him to cite it as confirmation that Gouzenko was muddling things. Instead, Liddell focuses on ‘old’ news – the rumour of an unidentified British agent in Moscow. This was an essential part of the ‘BSC Report’ (see above), but now enhanced by the additional insight that the medium through which ELLI communicated this information was the Military Attaché in London. (Tyrer hypothesises that Hollis may have been the interrogator in this case, but then wisely immediately rejects his suggestion.)

Was Liddell really not paying attention? He had already discounted Uren of SOE as being ELLI, but the fresh news about the Military Attaché should have reminded him of his previous analysis. As I conjectured, Liddell and Dwyer were back in September probably told much more than the bare cables reveal. He should have immediately cast his mind on the few characters who had contact with the Attaché, Colonel Chichaev (as he apparently did, after some reflection). Yet he should also have displayed a little more concern about ELLI than expressing relief that he was probably not a member of MI5: if there were spies at large in any service in London (such as Uren), it was MI5’s responsibility to root them out.

And it was on November 16 that Liddell recorded his follow-up with Air Commodore Archie Boyle:

I am getting the personal files for all the representatives of the SOE mission. Neither Hill nor Graham of course really fits the bill since the only apparently concrete piece of evidence by CORBY is that he decyphered two telegrams indicating that ELLI was in London and worked through the Soviet M.A.

Here Liddell consolidates his impressions. He articulates the link between ELLI, Chichaev, and George Hill, and manifestly confirms the fact that Gouzenko had stated that had deciphered the telegrams from ELLI himself – the nugget from the October 29 interrogation. And he adds the audacious footnote:

ELLI=ALLEY is I think too fantastic to merit any serious thought

This led to the flurry of activity at the end of November that I described in coldspur in May.

7. The interview by Roger Hollis on November 21:

William Tyrer is again to be credited for extracting from MI5 the contents of the two-page telegram sent by Hollis on November 23, two days after his interview with Gouzenko. (The National Archives created a new folder for it in KV 2/1425B, released in November 2014, and added to the catalogue on July 3, 2015. Confirmation of the event had been referred to in a minute of May 23, 1946, visible at sn. 216a in KV 2/1423.) This encounter surely did not occur ‘on the shores of Lake Ontario’ (as fancifully reported by Dick White): Hollis would not have travelled five hours for what was later described, rather imaginatively, as a three-minute interview. Mahomet came to the mountain. I present the text:

A. I paid a brief visit to CORBY on Wednesday. He makes a good impression as regards his honesty and truthfulness.

B. I dealt particularly with ‘ELLI’ case, the position of which is as follows:

1. CORBY himself deciphered 2 telegrams from Soviet Military Attaché in London, one stating ELLI was now going over to DUBOK method and the other that British Military Attaché in Moscow would not give name of agent there.

2. LIUBIMOV * told him in 1943 that ELLI was a member of a high grade intelligence committee, that he worked in British counter-intelligence. CORBY thinks that LIUBIMOV mentioned the number 5 in connection with committee.

3. KOULAKOFF in 1945 told CORBY that a high grade Soviet agent was still working in United Kingdom. He did not specifically say this agent was ELLI and appeared unwilling to discuss matter. CORBY did not press it.

4. CORBY told me that he did not know that the two incidents of the theft of the papers from Military Attaché in London and attempt to Telephoto his office were reported by ELLI.

5. I tried to get some further indication of the nature and scope of information supplied by ELLI: for instance I asked whether he supplied information on German war dispositions, political matters, etc. CORBY said that he did not know and refused to be led in these matters and I think it is quite clear that he knows nothing more about ELLI than information given in previous paragraphs.

[* ‘The name ‘LIUBIMOV’ appears in the texts sometimes as ‘LUBIMOV’. I have reproduced the original spellings as they lie. Similarly with ‘KOULAKOFF’ and ‘KULAKOV’.]

Hollis’s account is enormously provocative. Item 1 would appear to point to Chichaev as the Military Attaché (rather than the head of the GRU station), since Hollis associates him with his counterpart in Moscow, and the reference foreshadows the item in 4, which without a doubt refers to thefts from Chichaev’s lodgings. If Chichaev was indeed familiar enough with the methods of communicating with ELLI, it sounds as if ELLI was directly controlled by Chichaev. This is a puzzling revelation, as it would draw attention away from any casual but authorised relationship (such as that with Stephen Alley), and point to a much more clandestine affair.

On the other hand, the description of the behaviour of the British Military Attaché in Moscow is bizarre. It suggests that a) George Hill had been presented with this information, and b) he did not deny that he ran an agent, but declined to identify him. Why would Chichaev be reporting this information from London rather than Ossipov in Moscow, and how would ELLI have learned about it? It would require a highly amicable and cozy relationship between Chichaev and Hill (as well as a secure method of communication) for them to discuss the matter. One would have expected Chichaev to warn his bosses in Moscow, and for Ossipov to challenge Hill, but, even if the response travelled back to Chichaev, he would not have seen any point in echoing it back to Moscow.

The only other interpretation must be that Hill had a meeting with Chichaev when he returned to Britain in the summer of 1942. Hill had been enormously indiscreet in sending letters to his contacts in SOE, especially John Venner, the finance director, about his plans for an ‘undercover operation’ in Moscow, and his messages may have been intercepted by the NKVD. He made another trip back to London in March 1943. Thus the tip may have come from Ossipov, Chichaev was assigned to verify it, and the story about the agent had nothing to do with ELLI. In any case, Hill’s inability to deny the rumour is puzzling.

The identity of the committee named in Item 2 is also problematic. Tyrer deftly referred to the Cram papers that contained a communication between Bourdillon of MI5 and the CIA in 1984, where Bourdillon claimed that Hollis interpreted Gouzenko’s reference to ‘M5’ [??] as ‘MI5’. How he arrived at this conclusion is not clear, but Tyrer adds that, a few months later, Bourdillon reported as follows:

Pincher makes a case for Hollis being Gouzenko’s ELLI. Actually the Gouzenko ‘ELLI’ lead was terribly vague and contradictory, and did not lead to MI-5 at all.

Nothing much more needs to be said about Item 3. Item 4, on the other hand, encourages further analysis. As I reported in May, I have discovered the ‘facts’ about the burglary from the Chichaev residence in April 1942 (and can thus provide an update to Tyrer’s article), in Chichaev’s file at KV 2/3226, but a full analysis is outside the scope of this discussion. Hollis’s language is irritatingly imprecise, however. It could be interpreted as saying that Gouzenko knew about the incident with the papers, but was not aware that it was ELLI who had reported it, or it could mean that the whole anecdote was new to him. Yet it seems to suggest that Hollis knew about the incident, and even that he, Hollis, knew that ELLI was involved. The latter interpretation cannot be correct, surely, given how recently ELLI had entered MI5’s realm of interest. In any case, it shows a disastrously cavalier approach by Liddell and co. not to have followed up on this ambiguity, and to have failed to ask Evans/Dwyer to clarify what Gouzenko actually said.

I have also covered Item 5 in previous research. It expressly reflects Hollis’s knowledge about MI14, part of the Directorate of Military Intelligence specializing in Germany, and the stealing by Leo Long in April 1942 of papers deriving from ULTRA, and subsequently passed to Anthony Blunt. Hollis was thus presumably trying to ascertain whether Leo Long could have been ELLI, but his question predictably fell on stony ground.

Hollis’s final claim is somewhat preposterous. He may have been speaking out of ignorance, if he truly had not seen any of the previous ELLI material [!], but other offerings, in particular the ‘BSC Report’ that he had brought back with him in September, conveyed more information – such as the suggestion of Russian descent. The lack of follow-up is yet more evidence of the slipshod approach taken by MI5’s top counter-intelligence officers.

8) The RCMP Report (November 1945):

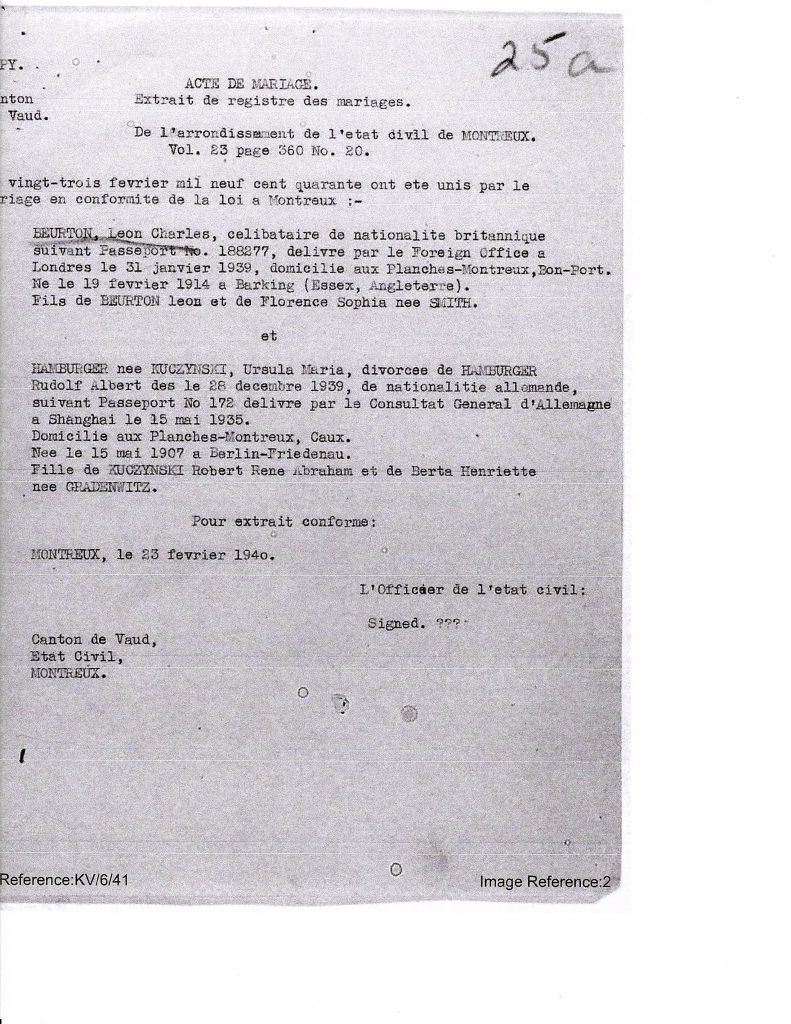

The report titled ‘Soviet Espionage in Canada’ issued by the RCMP Intelligence Branch in November 1945 (inspectable at KV 2/1428) offers valuable information on the structure of GRU intelligence in Moscow, and also includes, under Chapter 7, ‘Distribution of Agents’, both Ignaci Witczak in Los Angeles, and Arthur Steinberg in Washington, as well as ‘ELLI’ in London. It also offers an intriguing insight into the contact that Hermina RABINOVITZ (who had worked for the International Labour Organization in Geneva) had with members of the Red Orchestra in Switzerland (e.g. SISI, LUCY, ALBERT and PAUL), although a whole page has been redacted. Under the Alphabetical List of Cover Names, ‘ELLI’ re-appears, defined as ‘Unidentified agent in England in 1942-1945’, but it should not be interpreted from this that ELLI was in contact with Zabotin and the Ottawa-based ring. Another bizarre tip is that LUCY is defined as ‘Czech diplomat in Switzerland’ (with ‘?’ beside it, which raises intriguing questions about the Roessler/Sedlacek conundrum (for further information, see https://coldspur.com/sonias-radio-envoi/).

9) The Testimony to the Commission:

The hearings of the Taschereau-Kellock Commission began on February 6, 1943, and Gouzenko gave his first deposition on February 13. According to the record, Gouzenko was asked by Commissioner Taschereau whether he could read and write the English language, and Gouzenko answered in the affirmative. His spoken English may not have been so good, and Black was on hand to assist with translations and technical terms. In The Master Spy, Philip Knightley referred (p 134) to an oblique reference to ELLI in the evidence that Gouzenko provided. He wrote: “Instead [of Gouzenko’s pointing out the oddity of there being two spies in the West with the same code name], the possible existence of a second ELLI emerged, almost as an afterthought, in Gouzenko’s evidence before the Royal Commission”:

Q: Do you know whether ELLI was use as a nickname or covername for any person other than Miss Willshire?

A: Yes, there is some agent under the same name in Great Britain.

Q: Do you know who it is?

A: No.

Alternatively, the exchange ran as follows, as The Gouzenko Transcripts records. After Commissioner Taschereau pointed out that K. Willsher, secretary to the High Commissioner in Ottawa, possessed the cover name ‘ELLI’, the dialogue went as follows:

GOUZENKO: That is right.

TACHEREAU: And there is also a cover name ELLI, and I understand that he or she, I do not know which, has been identified as an agent in England?

GOUZENKO: That is right.

TACHEREAU: Would that be the same person?

GOUZENKO: No.

TASCHEREAU: You are sure of that?

GOUZENKO: As far as I know.

TACHEREAU: Did Miss Willsher come from England or is she Canadian born?

In whatever form it appears, this is an odd exchange, as if the questioner were absent-mindedly introducing the fact, and catching Gouzenko off-guard. Gouzenko did not appear to want to discuss the matter, and the question was not pursued. Taschereau must surely have been familiar with Willsher’s biographical details by that time, but he clumsily introduced a reference that the intelligence authorities would probably have preferred to keep concealed. Likewise, given the calendar details, Gouzenko must have known for sure that the two ELLIs were not the same person. The London ELLI does not appear in the official Commission Report published on June 27, 1946, which focused on the espionage ring in Canada, with only occasional straying into connections in the USA and Switzerland.

One important aspect of these revelations about the USA, though not directly related to ELLI, is the fact that Peter Dwyer was forced to admit, several years later, in 1953, that in 1946 he had passed on to Lish Whitson of the FBI strong indications that Harry Dexter White was a Soviet agent, and recommended that he should not be appointed to the International Monetary Fund. Edgar Hoover had admitted that he received such a confidence from a ‘Canadian official’. What was especially egregious is that Dwyer had not informed his Canadian hosts of this secret message. This story is inspected in detail in Mark Kristmanson’s Plateaus of Freedom: Kristmanson suggests that Dwyer’s coyness over the episode may have been attributable to the fact that he did not want to spill the beans about the fact that British Intelligence may have been in touch with Gouzenko before he defected.

Dwyer probably elicited this information when he was able to interrogate Gouzenko during the hearings. Apart from the embarrassment that the incident caused, it is noteworthy for the fact that it may not have been the only item of intelligence that was suppressed. In a television programme in the 1960s, Dwyer (who was a very cautious man with great respect for confidentiality), let slip that, apart from the hints that led to the arrest of Alan Nunn May, the remainder of Gouzenko’s information was ‘crap’. That was obviously a jocular observation that went too far the other way in minimising the significance of other revelations, but Kristmanson explores, rather ponderously, the paradoxes and gaps in the Gouzenko record, including the claim that Stewart Menzies himself was in Ottawa when Gouzenko absconded – a story I explored in an earlier piece (see https://coldspur.com/on-philby-gouzenko-and-elli/ ). Kristmanson thereby suggests that MI6 had a greater hand in Gouzenko’s defection than the available archive shows us. These theories will have to be analysed in depth at another time.

10. The interview by Guy Liddell:

This event in March 1946, when Liddell extended his tour of the United States to visit Canada, needs to be recorded, as expectations for an encounter with Gouzenko should have been high. Liddell’s Diary entry is the only known reference to it, and, as I explained in my May piece, what he wrote down for posterity shows a complete avoidance of any discussion of ELLI. That in itself may be significant. In Their Trade is Treachery, Chapman Pincher had asserted that the Canadian Government had strongly warned Gouzenko against mentioning ELLI – even in his memoirs, and that caution may have been prompted by the accidental revelation described in Item 9 above. Nevertheless, Gouzenko’s silence about the London ELLI when speaking to Liddell must have other causes.

11. A possible second interview by Roger Hollis:

At KV 2/1423/2, sn 216a, appears an unsigned telegram to New York (no. 762) dated May 23, 1946. The text runs as follows:

A. In conversation with Hollis Corby mentioned that directions came from Moscow to Ottawa Embassy for political activities of Canadian Communists.

B. These directions were communicated from the Embassy by open contacts such as Press Correspondents.

C. Please ask Corby what Section of Official in the Embassy handled this political work and what department in Moscow issued the directions.

A handwritten note adds: “cf. PF.66962 sn. 26a – pres[ume]. this refers to the meeting on 21.11.45.” If a reply was received (and saved), it has not been released from the archive.

While not directly relating to ELLI, it is interesting because the note implicitly suggests there may have been a second encounter between Hollis and Gouzenko. And, as William Tyrer shrewdly observed,: “ . . . the ELLI/Hollis telegram is serial 25a not 26a, and Canadian Communists are not mentioned in the ELLI/Hollis telegram.” Guy Liddell was fairly disciplined in noting the absences abroad of his colleagues, especially White, Hollis and Sillitoe. Liddell did not return from the Americas until April 26, and, since Hollis was reported to be busy with leakages during May, it seems highly unlikely that he would have been afforded another visit to Canada during these months. The source of the ‘Canadian Communists’ factoid remains obscure.

12. Commentary on the Hollis report:

This fragment derives from the correspondence between MI5’s Bourdillon and the CIA. I quote directly from Tyrer’s article in the International Journal of Intelligence and Counter-Intelligence:

Later, he [Gouzenko]expressed suspicion as to why his MI5 interviewer was so brief when so much more information could have been added. The extract from the memo from Bourdillon at MI5 to the CIA states that Gouzenko had read the telegram from Hollis one year after their meeting. Bourdillon added: “Gouzenko commented that some of the statements made in the telegram were untrue.”

To which specific statements Gouzenko is referring remains unknown, especially as serial 26a has not been released, and he may be referring to a report about a different meeting. But Gouzenko is said to have been upset about reports that he had said that British Intelligence had agent(s) within the Kremlin, so he may have been referring to point B.1. Notably, Gouzenko first provided the information about a British agent in Russia to the RCMP, and not to Hollis, and it is included in their 15 September report. [the ‘BSC Report’]

As with many of these items, as many questions are raised as are answered. If Gouzenko was as truly disappointed at the paucity of information that Hollis had been able to extract from him, why did he not take it up with others, such as Dwyer, or even Liddell, when he came over a few months later? Why did he not write up a fuller deposition? And Tyrer’s observation in the passive voice (‘is said to have been upset’) is disappointingly vague. Who made this claim? And when was Gouzenko ‘upset’? Was it Chapman Pincher, who may have been putting ideas into Gouzenko’s head, who was responsible for some creative antedating? No record of Gouzenko’s comments from November 1946 resides in the digitised archive. If Tyrer is correct about the precise statement that Gouzenko was complaining about, however (and I am sure he is right), it would point to the fact that Gouzenko was trying to claw back his statements about the agent in Moscow as early as late 1946.

13. Statements in Gouzenko’s Autobiography:

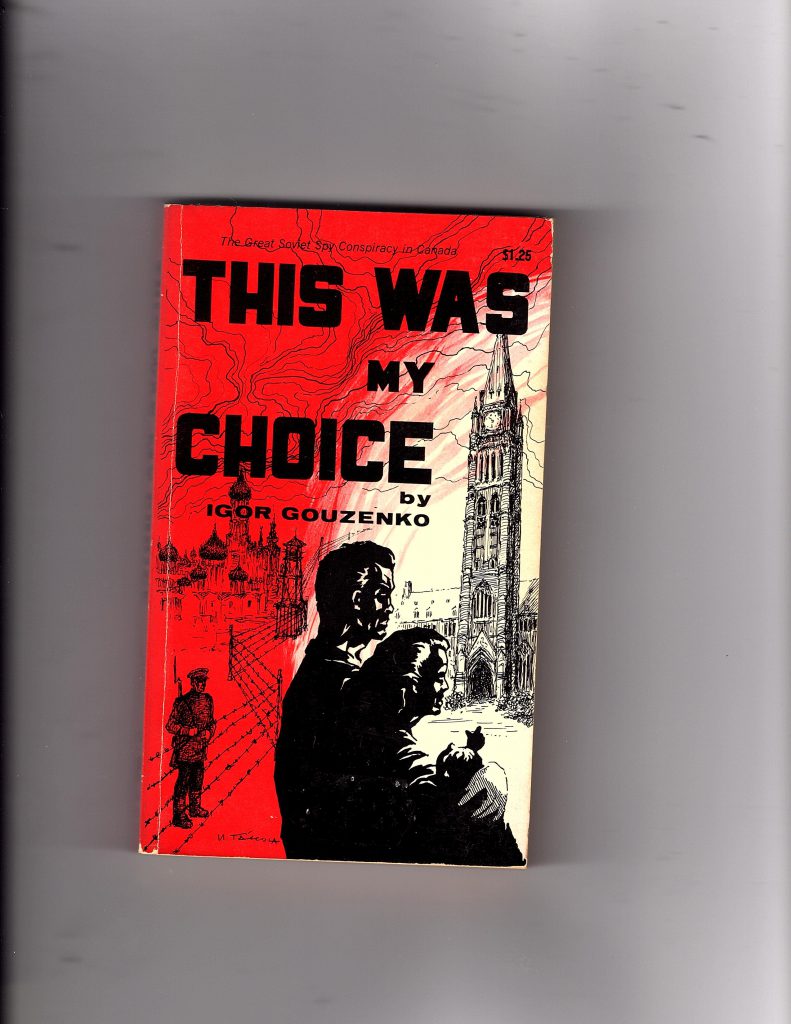

Gouzenko’s memoir, originally published as This Was My Choice in 1948, concludes with his escape in 1945, so it says nothing about his experiences with interrogation, or his encounters with MI5 officers. Unfortunately, it is also not very revealing about any relevant experiences as a cipher-clerk in Moscow or Ottawa: he was ordered to stay silent on these matters. (The memoir was largely ghost-written, in any case.) He does assert that there were thousands of Soviet agents in Great Britain – surely a gross exaggeration, but a statement that casts doubt on his overall reliability. He claims that, because he had ‘some nodding acquaintance with the German language’, most of his work ‘was on telegrams from and to Germany in Switzerland’. In that respect, he was exposed to the communications from Sisi (Dübendorf), Lucy (Roessler) and Alexander (Radó), a fact that adds an intriguing dimension to the Rote Kapelle business. Of his exchanges concerning cables with Liubimov on the English desk, he says nothing, although Liubimov appears in a grisly anecdote. Liubimov had been a Soviet officer on the Caucasian front, and had been ordered to shoot a captured German airman. One other insight that could be relevant is Gouzenko’s assertion that information of particular importance ‘was handed over in unedited and unabbreviated form to Molotov, Malenkov, or Stalin’. That would appear to reinforce the authenticity of the story of Poliakova’s actions in bringing immediately to Stalin’s attention the news that British Intelligence had a spy in the Kremlin.

14. Anne Last’s Notebook:

A curio in this collection is the notebook of Ann Last, who left MI5 in 1950 after marrying her colleague Charles Elwell, whom coldspur readers will remember from my coverage of Gordon Lonsdale and the Cohens (see https://coldspur.com/five-books-on-espionage-intelligence/ ). What makes her manuscript record so interesting is that Peter Wright suggests strongly (Spycatcher, pp 188-189) that it was only through reading the notebook, passed to him by Evelyn McBarnet, probably in 1961, that he learned the details of Gouzenko’s revelations. Wright reports:

According to Anne [sic] Last, Gouzenko claimed in his debriefing that there was a spy code-named ELLI inside MI5. He had learned about Elli while serving in Moscow in 1942, from a friend of his Liubimov, who handled radio messages dealing with Elli. Elli had something Russian in his background, had access to certain files, was serviced using Duboks, or dead letter boxes, and his information was often taken straight to Stalin. Gouzenko’s allegation had been filed along with all the rest of his material, but then, inexplicably, left to gather dust.

One must reflect that this may not be an accurate transcription of what appeared in Last’s notes, and Wright may have been recreating his account from information learned afterwards (or even inventing the whole episode), but it shows an eclectic use of sources, with information about Liubimov (Item 7), Stalin (Item 2), duboks (Item 7), Russian background, i.e. not ‘descent’ (Item 5), and access to files (Item 5). Yet it includes nothing about the knowledge of the spy inside the Kremlin, which is prominent in Items 1, 2, 5, 6 & 7. Moreover, Wright indicates that the information had been filed (‘left to gather dust’), but he then inexplicably fails to inform us whether he went to inspect that material presumably stored in the GOUZENKO and ELLI folders. Instead he makes out that its unavailability, and the lack of follow-up, were part of a devious plan by Hollis to conceal the traces of ELLI.

On the other hand, if the artefact is authentic, Last obviously believed that the ELLI investigations had been feeble, and confided her concerns to McBarnet. But why would she have to record all that information in a secret notebook, if it were available in the registry? Under what circumstances could she have read the documents, been conscious of the lack of follow-up, and also been aware that they had been concealed? McBarnet (according to Wright) said that both she and Arthur Martin (for whom she worked) dared not bring up the ELLI business to the current Director-General, Roger Hollis. The time of the Last secret notebook, however, was under the régime of Sillitoe, Liddell and White. It was the latter pair who had fallen down on the job, not Hollis. The whole melodrama is quite absurd.

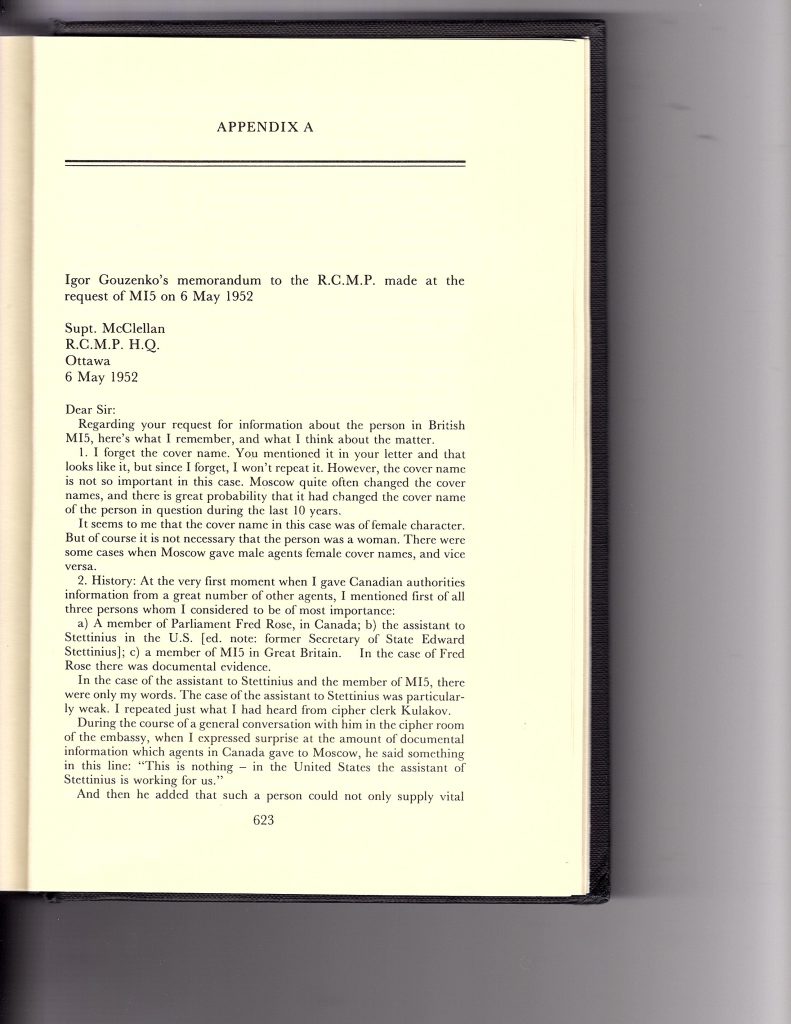

15. The statement to the RCMP:

This event has an interesting history. Chapman Pincher seems to be the sole source for the story. He wrote, on page 210 of Too Secret Too Long, as follows:

Early in 1952, as part of the inquiry into the identity of the Third Man, Dick White, then MI5’s Director of Counter-Espionage, decided that another look should be taken at Gouzenko’s allegation about the spy in MI5 with the code-name ‘Elli’. On 6 May Superintendent George McLellan of the Security Branch of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police asked Gouzenko, on MI5’s behalf, to submit a memorandum giving as much detail as he could remember of the circumstances in which he had heard about ‘Elli’. Gouzenko produced the document to which I have already referred and which is reproduced in Appendix A. The memorandum was classified Secret, and while Gouzenko was adamant that the spy had existed in 1942/43, and probably still did, it led to no result, much to Gouzenko’s disgust . . .

The memorandum became public only through a leak, through Gouzenko himself, to the Toronto Telegram in September 1970.

Guy Liddell’s Diaries provide us with additional information. Ever since the summer of the previous year, after the abscondence of Burgess and Maclean in May, the FBI had been pressing MI6 for further investigations into Kim Philby as the possible ‘Third Man’ who had warned the pair of Maclean’s imminent arrest. On July 7, Liddell recorded that Dick White had communicated to him Stewart Menzies’s deep concerns about Philby, in light of revelations about Philby’s first wife, Litzi, and a re-examination of the Volkov affair:

Dick said that it would be difficult for him to carry the enquiry any further on the assumption that Philby was identical with “ELLI” of the Gouzenko case, or that he was the “C.E. officer” mentioned by Wolkov [sic]. He suggested that Edward Cussen or Buster Milmo should be given all the evidence and conduct an enquiry. He doubted, however, whether any such enquiry could be conclusive: Philby would have to be told that the Americans suspected him of being ‘ELLI’ and that it was up to him to do everything he could to produce factual evidence to the contrary. This might, however, be extremely difficult.

This is a remarkably ingenuous observation by Liddell. First of all, it shows that the Americans were closely aware of the ELLI problem, and tracking it far more rigorously than the British. Second, it displays the fact that MI5 itself had not solved the question of ELLI’s identity to its satisfaction. Given the intensity of the investigation at the end of 1945, this is shocking. That is why one must posit the notion that perhaps Liddell and White were confident they had fingered ELLI already, but the nature of any disclosure would have been so embarrassing that they had to pretend that ELLI was an unsolved mystery. Yet this would rapidly inveigle them into further disarray, as the FBI would be able to accuse them of indolence and negligence. Either way, they were caught in a classic Morton’s Fork (not named after Churchill’s intelligence adviser, Desmond Morton, incidentally).

Indeed, the pressure increased. On August 20, Liddell created another diary entry where he made some rather silly analysis about the Burgess/Maclean business, and then tried to record excuses why MI5 had not been able to respond to the FBI’s comments on the paper on Philby that his department had written. He described his message to the unnamed contact (probably Cimperman, the CIA representative in London) in the following terms:

We had in fact, and were still, making exhaustive enquiries. Meanwhile, it was useless to interrogate a man who had all the cards in his hands. Until we get some fresh cards, and some pretty high ones, there was nothing in the way of interrogation that would be profitable. I hoped that he would express this view, with which he agreed, upon his superiors in Washington. They have been urging us to interrogate immediately on the more sinister allegations against Philby arising from the Gouzenko and Wolkov cases.

Again, Liddell had confidently expressed the opinion, back in late 1945, that ELLI was probably in SOE, and had pursued his investigations with Commodore Boyle. Now he is unable to assert that Philby could not possibly be ELLI. Nevertheless, amid all this turmoil, Liddell was able to take the month of September off on leave, but returned to find the pot still boiling, and the Philby case much blacker. On October 1, he recorded:

I saw the D.G. [Sillitoe] who told me about his interview with Bedell-Smith [the head of the CIA]. Bedell Smith was given certain facts about the PHILBY case, which he was told were still under investigation. It was, however, made clear to him that up to the moment these could only be regarded as a chain of co-incidences, all of which might have a different explanation. He seems to have got a somewhat false impression of this interview and told ‘C’ [Menzies] that we were now confident that PHILBY was identical with the man mentioned by GOUZENKO and by WOLKOV. This of course is far from the case.

‘Of course’! Liddell appears to have lost it by now. He is unable to separate the claims made by Gouzenko (very vague, and surely not pointing towards Philby), with those from Volkov (very damaging, and the occurrence of which had immediately caused wise heads to suspect Philby), and merely echoes the woolly understanding that he apparently attributes to both Sillitoe and Bedell Smith. The gross defects in his handling of the ELLI investigation should have been apparent to any sensible observer, but he and White must have been colluding, and Sillitoe was obviously too bemused by the whole business to ask any penetrating questions.

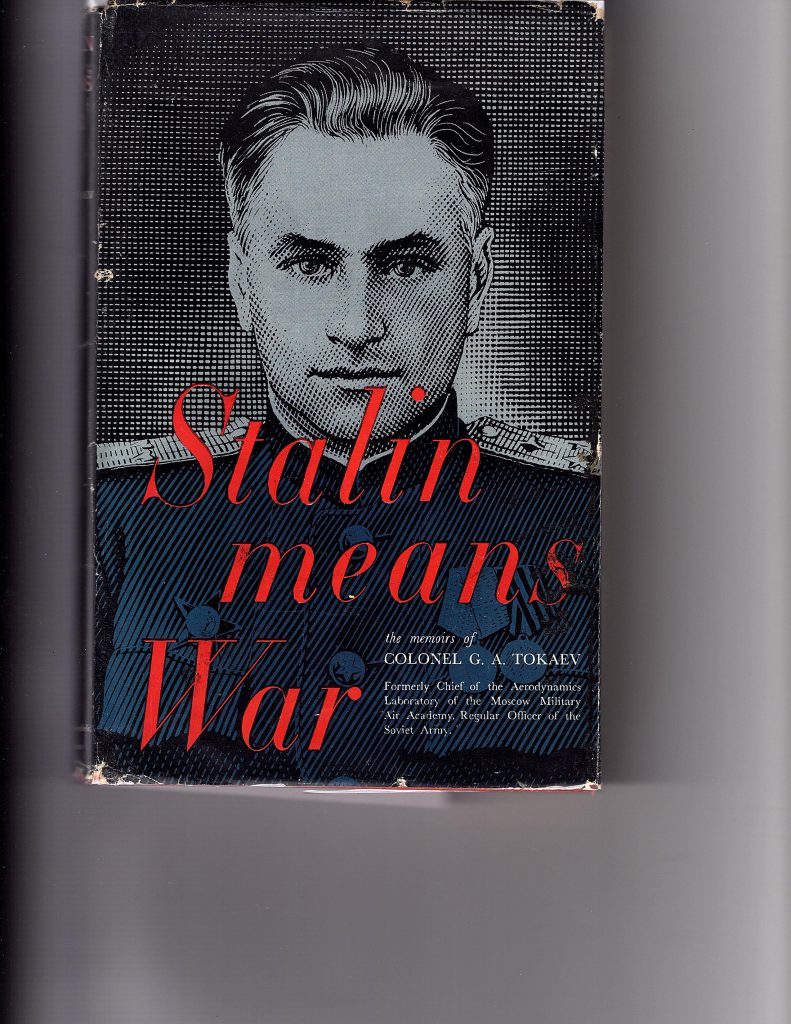

That is the last entry specifically on the pressure from the CIA. Dick White (after waiting a few months) presumably then took matters into his own hands, perhaps to show the CIA that MI5 was serious in resuming the quest for ELLI, resulting in the request to the RCMP that is described by Pincher. Gouzenko’s response is the most comprehensive extant document expressing his opinions. It is too bulky for me to transcribe in full, so I hereby display the four-plus pages as scanned objects, and attempt to summarise their main points instead.

* Gouzenko said that he had forgotten the cover name [‘ELLI’]. That is not important, as it may have changed. The fact that it may have had a female character does not mean the person was a woman.

* Gouzenko immediately gave the Canadian authorities three major names: Fred Rose, Edward Stettinius [former US Secretary of State], and a member of MI5 in Great Britain.

* The evidence of Stettinius and the MI5 member were only in Gouzenko’s words (i.e. no documents, as with Rose). His colleague Kulakov informed him that Stettinius’s assistant was working for the Soviet Union.

* Whittaker Chambers’s information led to the conviction of Alger Hiss, Stettinius’s assistant.

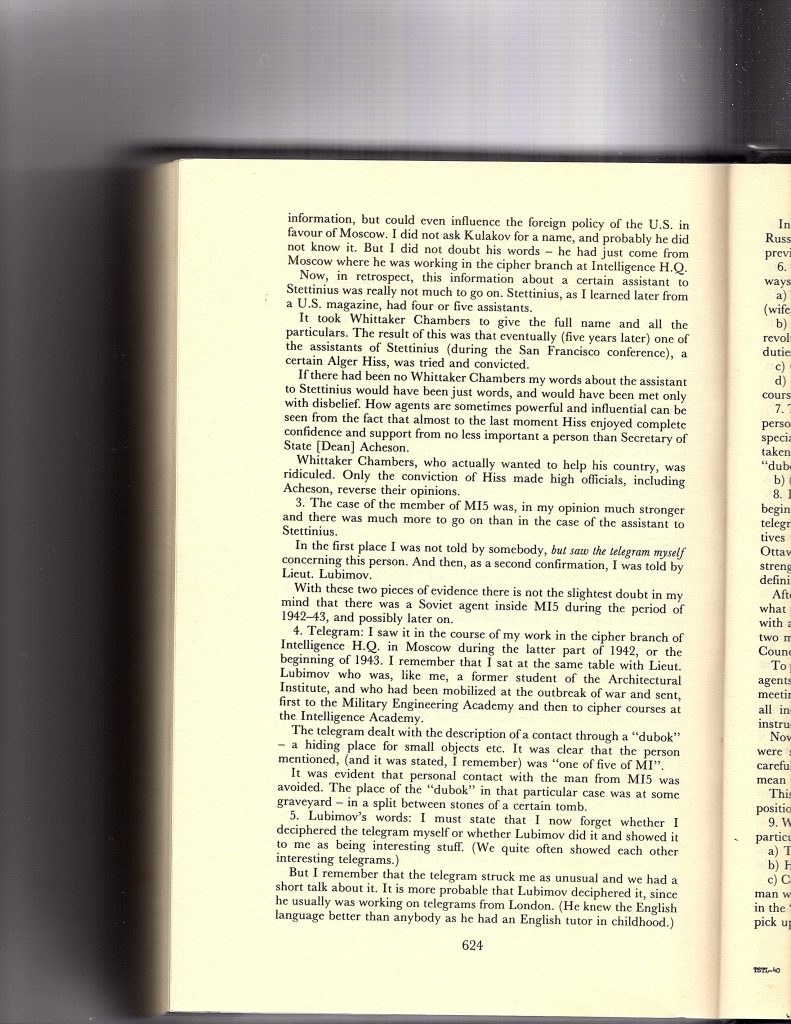

* As for the MI5 member, Gouzenko saw the telegram himself, and the information was confirmed by his colleague in Moscow, Lubimov

* Gouzenko saw the telegram at the latter part of 1942, or the beginning of 1943. It concerned the use by the man from MI5 of a dubok in a graveyard. The man was ‘one of five of MI’.

* Gouzenko could not recall whether he or Lubimov deciphered the telegram, but it was probably Lubimov, as he knew the English language better.

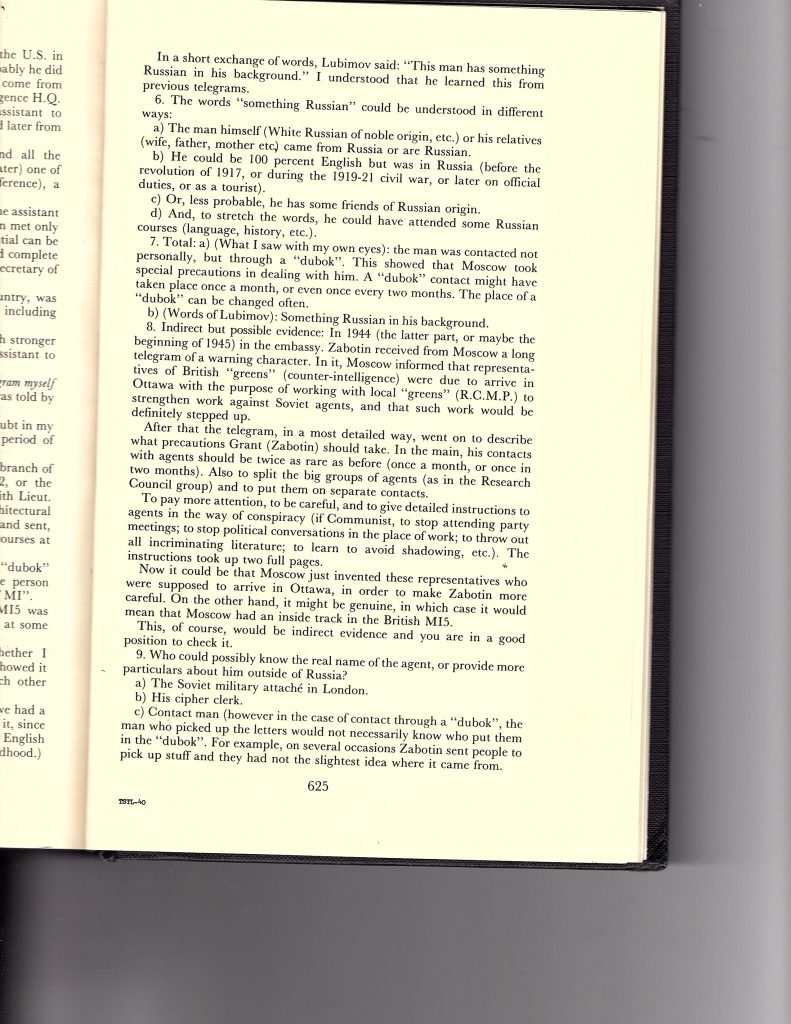

* Lubimov told him that the man ‘had something Russian in his background’ (which could mean a variety of things).

* In the latter part of 1944, or early 1945, Zabotin [head of the GRU station] received a message from Moscow warning of British counter-intelligence officers arriving in Ottawa. That required precautionary measures.

* Real name of agent might be known by a) Soviet military attaché in London; b) his cipher clerk; c) contact man (though that is not certain); and Maj-Gen. Bolshakov, formerly chief of First Intelligence H.Q. in Moscow.

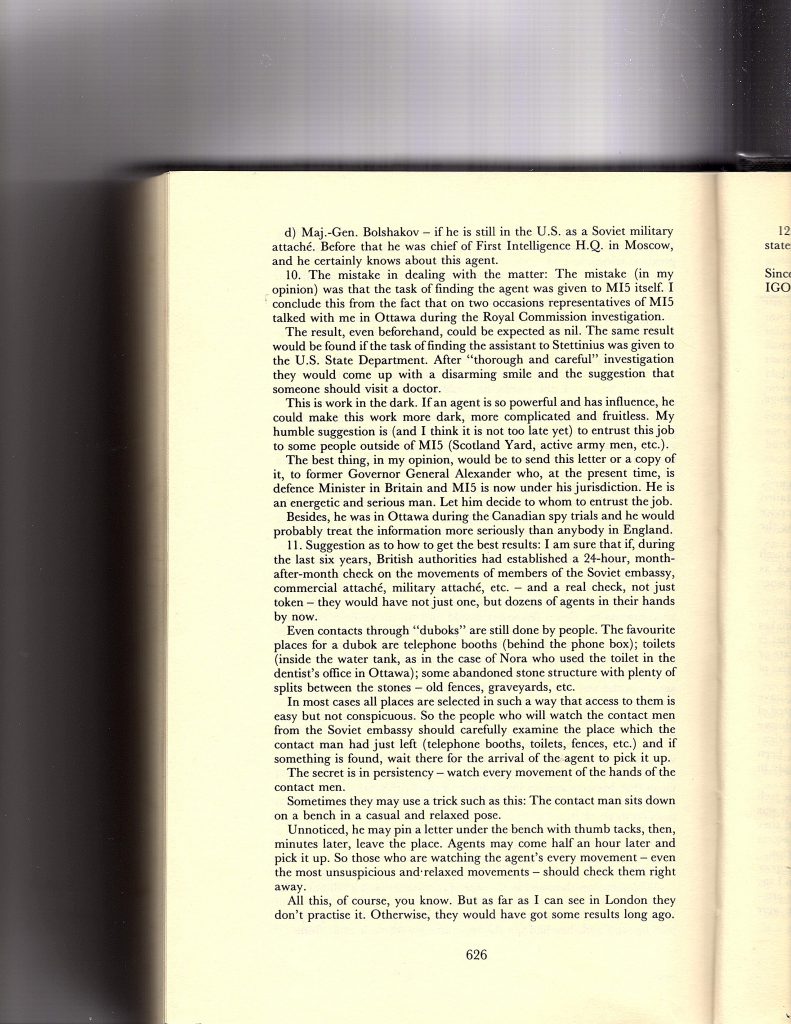

* The fact that the task of investigating the agent was given to MI5 was a mistake. It should be entrusted to Governor General Alexander, currently Defence Minister in Britain. [!!!]

* Persistent observations of members of the Soviet Embassy in London would have produced results. That clearly did not happen.

Again, this is quite a provocative statement. That Gouzenko had forgotten the name ‘ELLI’ (especially as there were two of them) is truly bizarre, and might indicate more that he had been instructed not to mention it at all. His concentration on the triad he named is surely erroneous: the most prominent name was that of Nunn May (ALEK), on whom the RCMP and MI6/MI5 immediately acted. Alger Hiss was an NKVD spy, not an agent of the GRU, which rather demolishes the theory of compartmentalization of GRU-NKVD processes in Moscow, and of the claim that Gouzenko and his colleagues knew only about the GRU (and that ELLI was necessarily a GRU asset, therefore). His claim that he saw the telegram himself is in apparent conflict with the statement that he made in September 1945 (Item 2: The BSC Report, above) where he ‘heard about’ him in Moscow. On the other hand, since Gouzenko, in 1945, much closer to the date, had stated that he had deciphered telegrams himself (Item 5), it would be an odd change of perspective for him now only to imagine that he might have done so. In fact, he had also told the ‘inattentive’ Hollis that he had deciphered two telegrams (Item 7, above), and had even informed Hollis about the second cable, where the inability of the British Military Attaché to give the name of his agent there was communicated – a fact that he surprisingly omits from his account here.

What is more, Gouzenko is now sure that the man was a member of MI5, whereas before he had indicated only that he was a member of the ‘British Intelligence Service’. The phrase ‘one of five of MI’ appears, but the exact Russian original of this expression is not given, and it would seem to be an unlikely representation of MI5. The original description of ELLI’s background (‘of Russian descent’: see the BSC Report) has now been made vaguer, referring to ‘something Russian in his background’. Gouzenko does, however, repeat the information about the ‘dubok method’ that he imparted to Hollis, and now adds the revealing information about its location, in a graveyard. This would also have repercussions later.

Even for making allowances for the passing of time, and the natural weakening of the memory, and possible problems in the original translations, this is a strange report. Though reputedly anxious to set the record straight, Gouzenko actually reveals less here than Hollis extracted from him in his infamous three-minute interrogation, and he studiously avoids the vexed issue of the unidentified agent cultivated and managed in Moscow. Was he perhaps tutored to pare back his story, and avoid mentioning embarrassing connections? Did he really forget the earlier testimony that he had given or believe that it would have been forgotten? In any case, he does not come across as a reliable witness.

But what happened when McLellan responded to White, presumably with a copy of the memorandum? Why is it not in the Gouzenko archive?

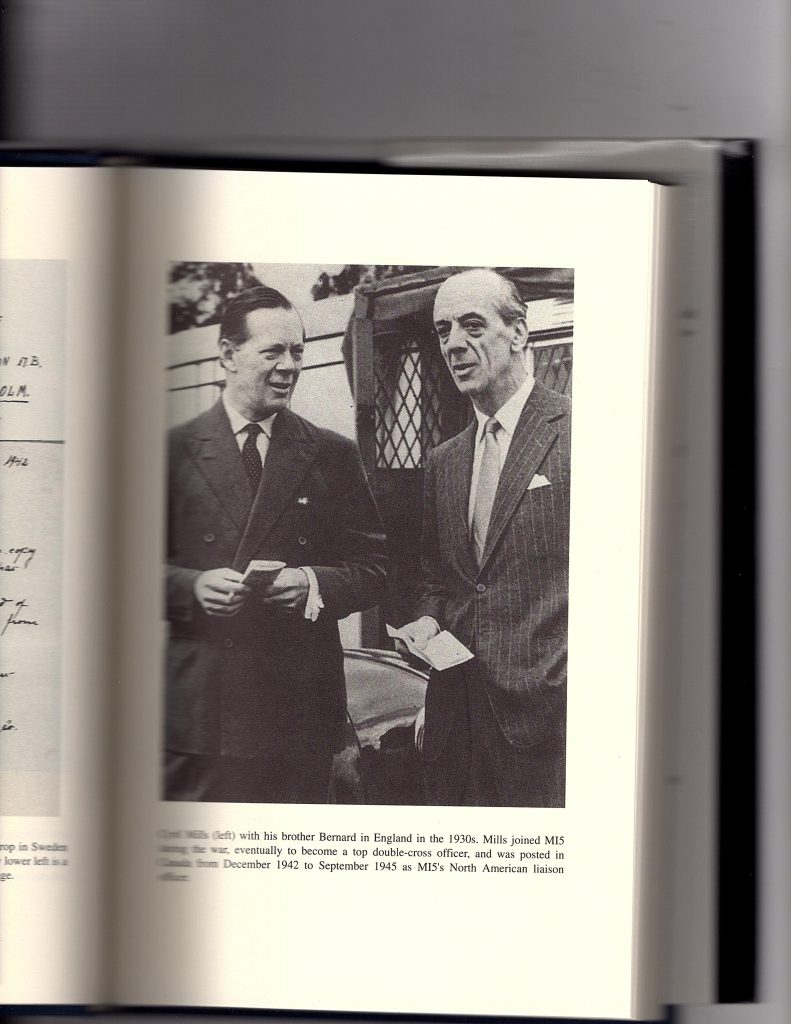

16. The memorandum from the FBI:

In my May report, I drew attention to Chapman Pincher’s focus on Gouzenko’s statements about the visit by British counter-intelligence officers to Ottawa, represented in the deposition above, as evidence of a leaker within MI5. I have since discovered that Liddell’s account of this refers to the same ‘recent statement’ by Gouzenko. It is almost certain that this statement is the same one as that appears in the memorandum triggered by Dick White’s request, but I include Liddell’s reaction here, since it reflects Liddell’s puzzling decision to focus solely on this aspect of what Gouzenko wrote, and it provides important clues as to how the Philby/ELLI investigation was progressing. Moreover, someone has inscribed ‘FBI’ in the margin of Liddell’s diary entry, perhaps to suggest that the source of the information did not come from Canada. The entry for October 3, 1952 runs as follows:

James Robertson and Evelyn McBarnet came to see me about a recent statement by GOUZENKO that he recollected a message in the latter half of 1944 which indicated that certain Counter-Intelligence personnel were visiting Canada and that there would be some general tightening up on Soviet activities. The message was in the form of a warning.

It appears that PHILBY had some conversation with T.A.R. [Robertson] before I left for the United States on July 17, and that my visit might possibly be alluded to in this message.

I said that my diary for this period showed that it was immediately prior to my leaving for the United States that we had for the first time contemplated close co-operation with the Americans on Communist matters. It had been suggested that the F.B.I. should send a representative over here, but this had been turned down by the State Department, who felt that such a close liaison on this matter might be politically dangerous if it came to the notice of the Russians. It was, of course, at this time that Roosevelt, and presumably also the State Department, were preening themselves on their own view that they had got Stalin eating out of their hands and would bring Russia back into the comity of nations. In the end it was agreed that I should go over to America. Although one of my objects in doing so was to discuss with Cyril Mills GARBO’s notional agent and the WATCHDOG case, I doubt whether I had much discussion on Communism in Canada.

It is possible that some intimation or collaboration by ourselves with the F.B.I. on Communist matters may have reached the Russians through the State Department, but I doubt whether it could have done so through PHILBY. His discussions with T.A.R. were much more likely to have related to the GARBO case.

If Liddell had to be informed about this statement by his underlings McBarnet and Robertson, does that imply that he had not himself seen the full memorandum produced by McLellan of the RCMP? Was the FBI the source of McBarnet’s and Robertson’s information? Had White perhaps not told any of them what he was up to, and concealed the report? (This episode, with McBarnet’s apparent ignorance of the details of the case, severely undermines Wright’s account in Item 14.) Why did Liddell not comment on the troubling revelations in the rest of it? Again, it is all very puzzling. The perennial problem in interpreting Liddell’s Diaries is that one can never be sure whether the absences of obvious commentary are due to a) the fact that he did not know what was going on; b) he knew, but did not want to record anything; or c) he recorded some observations, but the entry was redacted.

17. Senator Jenner’s Sub-Committee:

In 1952, Senator William Jenner was appointed chairman of a US Senate committee called the Senate Internal Security Committee, which investigated communist infiltration. Amy Knight covers its proceedings in How the Cold War Began, describing how, in the Steinberg investigations, Jenner and his colleague Senator McCarran had flown to Ottawa in January 1954, leading a sub-committee, to interview Gouzenko. Mark Kristmanson described it as follows: The gadfly George Bain explained to Globe and Mail readers that the Jenner subcommittee’s pressure tactics against Lester Pearson and their demand to re-interview Gouzenko were products of their lack of direct access to FBI files.” At the end of 1953, Gouzenko had declined an invitation to appear before them in the USA, citing security concerns. He had to clarify, however, that he had nothing new to tell about communist infiltration, but did have ideas as to how more defectors could be won over, and in particular named the cipher-clerk for the NKVD, Farafontov, as a valuable resource. During the interview he nevertheless brought up the subject of the British spy – something in which the Americans did not seem very interested. Knight conjectures that Gouzenko thought that the FBI should want to hear what he had to say because of the unresolved ‘Third Man’ debates, and the suspicions hovering around Philby, and was thus disappointed when the subcommittee, led by its counsel Jay Sourwine, maintained a distinctly parochial domestic perspective. It was evidently not going to go out if its way to help the FBI.

What is relevant is the fact that Gouzenko told Sourwine that he had disclosed all the information about the agent (he did not name ‘ELLI’) to the Canadian Royal Commission, and said that he had believed it had all been passed to the FBI (unaware, no doubt, that the FBI had frustrated the subcommittee). Since all the evidence points to the fact that ELLI was kept out of the discussions when he was formally interviewed, this may have been a lapse of memory. Sourwine was thus not impressed, forgetting Gouzenko’s public reminder of a couple of months back (quoted in the Toronto Telegram). To bolster his case, however, Gouzenko obliquely referred to his recent memorandum given to the RCMP. As Knight writes: “Speaking to the Jenner subcommittee, Gouzenko claimed he had written three pages about ELLI sometime earlier, but he did not say for whom.” She then goes on to quote (from the proceedings in the Canadian National Archive) that Gouzenko stressed the aspect of the ‘Russian background’ of the agent. “But from the telegram it as clear, and I also described in the detail the circumstances under which this telegram came to my attention.”

The ‘it’ looks unmistakably to refer to the fact that ‘ELLI’ had a Russian background. Yet, as the memorandum in Item 14 undeniably shows, this fact was not ‘clear from the telegram’: it was imparted to him by Lubimov. And Gouzenko did not there describe in detail how that telegram came to his attention. The one he described that he saw himself concerned the activity with the dubok and the graveyard. His testimony continues to show a pattern of minor inconsistencies.

18. The response to Stewart in 1972:

In the 1960s, Peter Wright (of Spycatcher fame) had made his unsuccessful approaches to the RCMP on Gouzenko, being told (in error) that the notes of his debriefing had been destroyed. Yet he surely would have had access to the Gouzenko and ‘ELLI’ files maintained by MI5, where he would have been able to learn about the defector’s original statements. Knight cautiously observes: “If Wright had seen the notes of Gouzenko’s RCMP debriefing he would have known that Gouzenko made no mention of MI5 to the RCMP”. More dubiously, however, she then reveals her own firm conviction about ELLI’s home, while ignoring the facts of Gozuenko’s denials: “Moreover, Gouzenko’s statements confirmed that ELLI was from MI6 because Elli was privy to information about a British secret agent in Moscow.”

Thus matters in the FLUENCY operation (the search for the mole, ELLI) moved sluggishly onwards. Maurice Oldfield of MI6 interviewed Dwyer for two days, unproductively. When Dick White, now head of MI6, visited J. Edgar Hoover in 1965, he confided in him that allegations had been made against Hollis, and that an investigation was under way. Yet none of the FLUENCY Committee thought to interview Gouzenko again, and that particular operation was wound down when Hollis retired.

And then came the strange events of 1972, when the investigation was picked up again, shortly before Hollis’s death in 1973. The only source appears to be Sawatsky, who in 1984 conducted interviews after Gouzenko’s death, and the story is told through the voices of John Picton and other journalists (Peter Worthington and Robert Reguly), and a lawyer named William McMurtry. Patrick Stewart of MI5 was sent out to Ottawa to interview Gouzenko, but exactly what material he brought with him, and what was shown to him by the RCMP, is very vague. Picton said that Stewart brought ‘a thick report’ with him. Knight guesses that it was the ‘BSC Report’, but that would have been a thin compilation. Gouzenko never gave enough information on ELLI or other spies within British Intelligence to cover more than a few pages. Here Knight adds that the RCMP had given Stewart the notes of the ‘original debriefing’ of Gouzenko, but it is not clear which debriefing she is referring to.

The extended commentary includes observations by the three journalists. No one appears to have stopped to ask: why on earth were three journalists invited to a confidential meeting between the RCMP, MI5 and Gouzenko? Was it a set-up? Worthington claimed that Gouzenko invited him, but did the RCMP give him permission? It is suspicious, because Gouzenko went off the deep end when he started reading the dossier, picking up the document that Stewart described as ‘the earlier interview with our fellow’, and claiming it was all lies. Now, the reference to ‘our fellow’ obviously points to Hollis’s interrogation at the end of November 1945, which occurred well after the ‘original debriefing’. Picton’s account is worth recording:

Gouzenko said he started reading it and threw it across the room. He said: “It’s all lies. It’s all lies. I didn’t say any of those things.” And apparently some of the things in there quoted him as saying that the British had a high-ranking mole in the Kremlin. “It’s not true. They couldn’t possibly have a high-ranking mole in the Kremlin, not when Philby was sitting as head of MI6.” And beside which, he said, the interview lasted only three minutes. He said: “I wouldn’t have had time to say those things.” He subsequently found out that the Mounties had exactly the same report in their files and never satisfactorily explained that.

I see multiple problems with this story. First of all, the claim about the mole in the Kremlin did not originate with Hollis: it appeared in early telegrams and in the BSC report (qv. Items 2, 5, 6, & 7). Philby was, of course, never head of MI6, and very far from that position in 1942-1943. The reference to the ‘three-minutes’ indubitably points to the Hollis interview, and RCMP would surely have a copy of Hollis’s report in their files. For Gouzenko to deny so strenuously the documented claims, and attribute it all to Hollis’s distortion of what he said, should have placed him on very shaky ground.

Yet the situation became even more bizarre and unlikely. McMurtry (the lawyer) stated that ’they’ (the RCMP and Stewart) ‘showed him the statement of his first [sic] statement and it was totally fabricated’. Worthington described how they went over the interview with him, and Gouzenko’s response was now a bit more justifiably peeved:

He said: “I’d never say this. Any intelligent person reading this would know it’s all nonsense and everything then would be discredited.” He said, for example, he was quoted as saying: “We in the Kremlin know – have a list of all the British agents who are inside the Kremlin.” Words to that effect. He said: “There are no British agents inside the Kremlin. It’s impossible for them to be there. They know they don’t have any. I know they don’t have any,” He said: ‘The only person who would put that in is someone who wants to discredit everything I’m saying.” Which I subscribe to.

As I have shown, no known archival material uses that language. Reguly then pointed out that Gouzenko claimed that the transcript had been doctored ‘to conceal references to a high-level spy in the British MI5 organization’, and Svetlana, Gouzenko’s wife, also invited, chipped in to report that someone had tried to emulate the handwriting of the interpreter Mervyn Black. A careful sleuth might have tried to establish which of Gouzenko’s statements Black had contributed to (as I have noted above, the date he joined the team is difficult to establish), but, in any case, the insertion was ham-fisted. Gouzenko was not allowed to take a copy of the document with him to compare it with samples of Black’s handwriting. The encounter ended in acrimony.

Amy Wright interprets this fiasco as an example of Gouzenko’s expressing frustration at the man from MI5’s (Hollis’s) perfunctory dealing with him, when Gouzenko was prepared to give him more information. But Gouzenko never had much more to say, Hollis extracted insights from him in real-time that he denied ever communicating when he had ample opportunity to give his full account, and Gouzenko treated as lies facts that he had described to other interrogators than Hollis. He was wrong to deny so strenuously the facts of his earliest depositions, but justified in accusing MI5 of fabrication.

Moreover, what Stewart and co. hoped to gain by their clumsy fakery is elusive. Maybe Stewart was innocent, but someone else appeared to have doctored the record in a feeble attempt to portray Gouzenko as a total flake. Why on earth did they think that ploy would succeed? And where was the report submitted by Gouzenko in 1952, and presumably in White’s hands shortly after? Was it not filed, and made available to Stewart? Why had Stewart not perused the early telegrams, the BSC report, and the Hollis account, where he could have established a defensible record of Gouzenko’s statements? At least he would have had something definite to chew on, and to debate with Gouzenko in the light of his earlier statements. The whole incident is farcical, but the evidence suggests that it was staged, to provide an inauthentic story that Hollis had doctored the records, and for Gouzenko’s aggrieved reaction to be public.

19. Communications with Chapman Pincher:

The veteran journalist – and persecutor of Roger Hollis – claimed multiple exchanges with Gouzenko over the years, some in meetings, some in letters, some over the telephone. These events are described in Pincher’s three primary books: Their Trade is Treachery (1981 & 1982), Too Secret Too Long (1984), and Treachery (2009 and 2012). This resource is not yet inspectable. Pincher’s archive is held by King’s College, London. A note on the web-page states: “Notes and correspondence relating to Pincher’s investigative journalism on British-Soviet espionage during the Cold War, 1950s-1980s, CLOSED, pending cataloguing.”

I shall paraphrase the important passages (readers can easily inspect the full text in Pincher’s books), and provide some straightforward commentary.

Their Trade is Treachery: