1. Introduction

2. Déricourt’s Enigmatic Role

3. The ‘Double-Agent’ Examined

4. Déricourt’s Possible Status?

5. The Fragmentation of MI5

6. Déricourt’s Recruitment by SOE

7. The Passage to Gibraltar

8. Déricourt’s True Status

9. The Aftermath, and Research to Follow

10. Postscripts

Introduction

In last month’s bulletin (The Prosper Disaster), I surveyed the historiography of the fortunes of the Prosper network in France, drawing largely on Robert Marshall’s All the King’s Men and Francis J. Suttill’s PROSPER: Major Suttill’s French Resistance Network. These observations should be viewed alongside my earlier commentary on Patrick Marnham’s recent War in the Shadows, which provides a deep analysis of the archival material available and which inspired this current round of research. (See Claude Dansey’s Mischief, and Let’s Twist Again.)

I now turn to providing my own analysis of the records at The National Archives (at least, some of them, since I am largely reliant on gaining photographs of undigitized files) to explore the circumstances of Déricourt’s recruitment. In this project, I find that I deviate somewhat from the conclusions to which Marshall (who did not have access to archival material) and Marnham came, and I shall take pains to explain why I think some of their conclusions – but not the major one concerning deception and betrayal of the Prosper circuit – may be flawed. The most controversial aspect of this case is the status of Déricourt as a ‘double-agent’, a term that has regrettably been overused and abused in much of the literature, and I shall explore that controversy first before turning to my inspection of the files themselves.

Early next year I shall provide a deep analysis of War Cabinet records from the first half of 1943, in order to clarify some of the bizarre decisions and activities that took place to support Allied deception exercises in Northern France as a prelude to the OVERLORD landings of 1944.

I recommend an episode of the Athena series ‘Secret War’, released on DVD in 2011, for a vivid recapitulation of the Déricourt affair. Episode 10, titled ‘The French Triple Agent’ (thus designated by the editors because he worked for SOE, SIS and the Gestapo) mixes some engrossing historical footage with some unmelodramatised re-enactments, and includes much provocative commentary by M. R. D. Foot, as well as some astonishing clips of Buckmaster’s TV interview in 1958 by John Freeman, of which I should have liked to see much more. The lessons are, however, inconclusive, and the narrative suggests that SIS learned of Déricourt’s contacts with the Gestapo only in April 1943. While pointing clearly at Buckmaster’s incompetence, and Dansey’s devilry, the programme evasively steps away from its early suggestion that a deception activity for COCKADE was behind the betrayal of the Prosper network, and it makes no mention of The London Controlling Section, Bevan, Double-Cross, the Twist Committee, or the details of the critical Operation STARKEY.

Déricourt’s Enigmatic Role

“An SIS ‘spotter’ at LRC quickly identified Déricourt as a German agent and turned him.” (Patrick Marnham, in War in the Shadows)

“Throughout 1943 Déricourt had been run as a XX Committee double-agent by SIS as part of STARKEY.” (Patrick Marnham, in War in the Shadows)

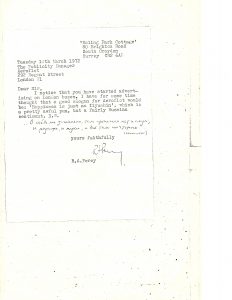

“If anyone starts accusing one of my organisers of being a double agent . . . all work in the field between us and the agent is likely to be suspended without any guarantee of a satisfactory decision from security one way or the other.” (Maurice Buckmaster, in unsent letter to Mockler-Ferryman, 15.2.44)

“In point of fact the arrests which F Section circuits suffered from time to time did not at all correspond with Lemaire’s [Déricourt’s] potential as a double agent.” (Maurice Buckmaster on 27.7.44)

“Christmann says that Déricourt could have been one of Britain’s most brilliant double-agents.” (Jean Overton Fuller, in Double Webs)

“He [Déricourt] said that on 2 June 1943 he was visited by two Germans . . . He accepted the ‘Doctor’s’ offer to work for the Germans. . . . From then on ‘Gilbert’ became a double agent. But he insisted at his trial that he worked honestly for the British, and only ‘feigned to work for the Germans’.” (E.H. Cookridge, in Inside SOE)

“The mistakes and failings of the British agents and their French colleagues are generally characterised as human weaknesses not treachery, although such a word seems applicable to the double agent Henri Déricourt.” (Mark Seaman, in Foreword to Francis J. Suttill’s Prosper)

“Such a proposition does not stand up to detailed examination in the two related cases cited most often: the attempts in 1943 to persuade the enemy that a second front was imminent, and the duplicity of Henri Déricourt, SOE’s air operations controller, and maybe a double agent run by SIS against the SD.” (Nigel West, in Secret War)

This selection of quotations from the literature on Déricourt should immediately provoke the following questions: “Was Déricourt originally recruited by the Germans, and then ‘turned’ by the Allies? Or was he an agent of SOE, whose past connections with German pilots led him to be ‘turned’ by the Sicherheitsdienst, and thus used against the Allies?” And the unavoidable conclusion must be that no one really knows. Moreover, once a recruit for one service starts talking to the other side, no intelligence or counter-intelligence agency can really know where the individual’s loyalties lie, and it must be unsure of its ‘ownership’ of him or her. The claims made in these statements include some troublesome contradictions.

In War in the Shadows, Patrick Marnham presents a bold assertion that Déricourt, in September 1942, was identified at the London Reception Centre (LRC) at Wandsworth as a German agent and then ‘turned’ (p 264). He states that the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) had already recruited him, paid him handsomely, and given him his BOE.48 moniker (p 263), before he left Vichy France. He describes Déricourt as ‘a Gestapo agent unmasked on arrival in England and sent back into France to work within and betray a circuit . . .’ ( p 276). On the other hand, E. H. Cookridge echoes the claims that Déricourt himself made – that he was a loyal British agent until he was visited on June 2, 1943, by two Germans ‘whom he had known before the war as Lufthansa pilots’. After the war, when he was charged with treason by the French DST (Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire), Déricourt claimed that he had no choice but to accept the Gestapo demand. Obviously one of these assertions must be wrong – maybe both. They are worth analyzing in more detail.

Marnham, by stating that Déricourt was ‘turned’, overtly suggests that the Frenchman’s then current allegiance must have been to the Nazis. (Marnham’s citation of Keith Jeffery in his Endnote as the source of this assertion is slightly misleading: the authorised historian of MI6 merely confirms that the service had ‘spotters’ at the LRC, and does not mention the Déricourt case at all.) Marnham does not explain, however, how the MI5 officer(s) interrogating him knew that he was a German agent already (unless Déricourt himself said so), nor by which threats, or ideological conversion process, Déricourt was convinced to switch his loyalties, or, even more importantly, how SOE knew he was not bluffing when he declared his commitment to his new masters. Marnham then goes on to say that, as a consequence of this process, Déricourt was run as a double-agent by the XX (Double-Cross) Committee as part of the STARKEY deception operation. (Marnham rather confuses his argument when he claims that Déricourt became a ‘double agent’ only when he contacted Boemelburg, i.e. by virtue of his first mission, shortly after his arrival in France in January 1943: see p 251 of War in the Shadows.)

That claim concerning Déricourt’s disposition, however, would imply that the XX Committee (or the TWIST Committee, that ran alongside it for a while) had every confidence that Déricourt would reliably carry disinformation with him overseas to his erstwhile German masters without revealing to them what had happened. Moreover, the committee would have to assume that the Gestapo believed that Déricourt had not switched his loyalties, but had infiltrated the British intelligence structures under false pretences. Yet the more seriously that British intelligence (in any department) considered that Déricourt might have been a German agent, the more cautious they should have been in turning him loose in France. For SOE/SIS had no control over Déricourt’s movements, or what he said, while he was in France, and the Germans, correspondingly, must have wondered how Déricourt had succeeded so easily in gaining the trust of his new employers, and whether the information he carried back to them was reliable or not.

Cookridge, on the other hand, quotes the trial transcript of the Permanent Military Tribunal at Reuilly Barracks from June 1948. Here Déricourt stated that the Germans told him that they knew all about his activities, his arrival by parachute and his journeys to England, and that they threatened to shoot him unless he agreed to work for them, also threatening to harm his wife should he abscond to England for good. Déricourt told his French interrogators that he continued to work loyally for the British, and only ‘feigned to work for the Germans’. “He never gave the Germans information which could have endangered his comrades”, echoed Cookridge, showing some naivety, and an unawareness of Déricourt’s betrayal of information. Yet the Gestapo was playing a similarly speculative game. They also lacked complete control over Déricourt, and, by letting him return to England, must have admitted to themselves that he might reveal the conversations and threats to his British employers, and that he might thus bring tainted information with him on his return (or even dispassionately betray his wife). Theirs was a far less dangerous enterprise, however: they were on home turf (if not native soil). They had infiltrated some of the SOE circuits already, and Déricourt was a dispensable associate whom they would manipulate as long as it suited them, but then abandon or dispose of if necessary.

Moreover, Déricourt was surely lying. When the Gestapo officer Hugo Bleicher was interrogated in July 1945, he stated that GILBERT had been working for the Sicherheitsdienst for some time before April 1943, and certainly during the period of the negotiations for the release of ROGER [Bardet] from the Sicherheitsdienst (see KV 2/830). Whatever the details were, this was a poor way to run a railroad, let alone a penetrative intelligence organization, as the conflicting expostulations of Buckmaster, given above, affirm. First, the Section F chief threatens the shut-down of the whole set-up should any of his officers be shown to be a double-agent (presumably abetting the cause of the enemy) and then reminds his audience of the opportunity of running Déricourt as a ‘double agent’ (presumably to help the Allied cause). Here was an officer out of his depth. Yet the mythology of the ‘double agent’ has persisted, and much of the blame can be laid at the feet of John Masterman.

The ‘Double-Agent’

“In this regard it is most important to remember that we are apt to think of a ‘double agent’ in a way different to [sic] that in which the double agent regards himself. We think of a double agent as a man who, though supposed to be an agent of Power A by that power, is in fact working in the interests and under the direction of Power B. But in fact the agent, especially if he has started work before the war, is often trying to do work for both A and B, and to draw emoluments from both.” (J. C. Masterman)

“It is the modus operandi of all double agents to provide thin material to begin with, coupled with an undertaking to deliver the earth tomorrow.” (SOE officer Harry Sporborg, quoted by Robert Marshall)

“The concept of the double-agent is well enough known to readers of the literature of espionage; it is understood well enough that the authorised double-agent may be instructed or licensed by his own side to contact the enemy and play in semblance the part of a traitor, in order to gain knowledge of the enemy’s work such as he could scarcely obtain unless she became part of the enemy’s working machine; but it is so often asked what price he has to pay? The authorised double-agent who pays in good faith too dearly is not, therefore, a traitor, though of course such a double-agent may always turn real traitor, and the dividing line might be hard to draw.” (Jean Overton Fuller, in Double Webs)

“But who is to say that these [patriotism and loyalty] will not fade under torture and turn the most steadfast agent into the most dreaded of all espionage weapons, the double agent?” (Alcorn, No Bugles for Spies, 1-2)

“Double agents are spies who secretly transfer their allegiance to an enemy secret service which uses them to confuse its foes.” (M. R. D. Foot in the Oxford Companion to World War II)

“A double agent is a person who engages in clandestine activity for two intelligence services (or more in joint operations), who provides information about one or the other, and who is wittingly withholding significant information from one on the instructions of the other or is unwittingly manipulated by one so that significant information is withheld from the other service. Peddlers, fabricators, and others who do not perform a service for an intelligence organization, but only for themselves, are not agents at all, and therefore are not DAs.” (CIA Field Double Agent Guide, 1960)

“Dvoynik – a double agent: An agent who simultaneously cooperates with two or more intelligence services, concealing the fact from each of them.” (KGB Lexicon, edited by Vasiliy Mitrokhin)

“But even before the end of World War II the term ‘double agent’ was discontinued in favor of ‘controlled enemy agent’ in speaking of an agent who was entirely under our own control, capable of reporting to his original masters only as we allowed, so that he was entirely ‘single’ in his performance, and by no means ‘double’.” (Miles Copeland, in The Real Spy World)

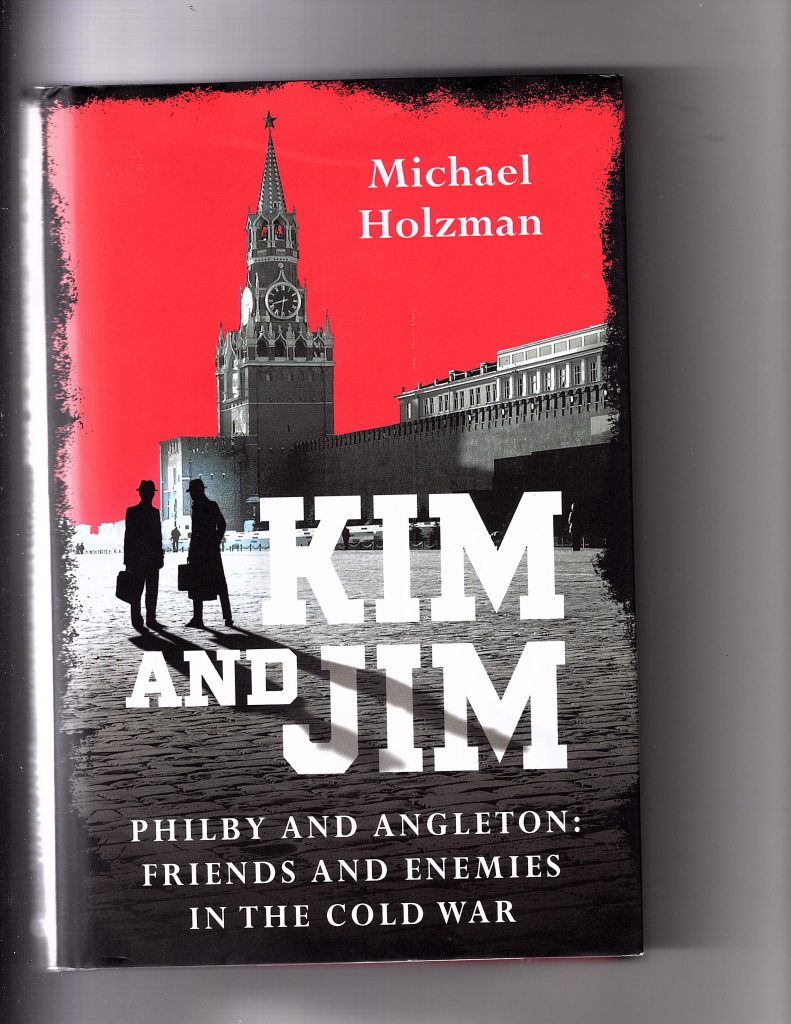

I have previously written at length about the phenomenon of so-called ‘double-agents’, and refer readers for a refresher to Double-Crossing the Soviets and The Mystery of the Undetected Radios, Part 8. I would change little in the analysis in the first piece, although I might change the description of ‘double-agents’ in the accompanying chart, and elsewhere use the terminology of ‘penetration agent’. My inspection of the terminology of ‘double agents’, ‘special agents’ and ‘controlled enemy agents’ in the second piece generally still holds good, I believe. Moreover, what I wrote about Philby is worth re-producing her, since Philby, the penetration agent and traitor, is often still irresponsibly described as a ‘double-agent’. One can go back to 1986, when Stewart Menzies’ wartime assistant Robert Cecil did so, in C’s War, through many incidences since then right up to the present day: for example, see the back-cover of Michael Holzman’s 2021 book, Kim and Jim, and frequently in the text of the book. Such misrepresentations cause an enormous amount of confusion with the reading public.

Thus the closest analogy to the strategy of the special agents is what Kim Philby set out to do: infiltrate an ideological foe under subterfuge. But the analogy must not be pushed too far. Philby volunteered to work for an intelligence service of his democratic native country, with the goal of facilitating the attempts of a hostile, totalitarian system to overthrow the whole structure. The special agents were trying to subvert a different totalitarian organization that had invaded their country (or constituted a threat, in the case of GARBO) in order that liberal democracy should prevail. There is a functional equivalence, but not a moral one, between the two examples. Philby was a spy and a traitor: he was definitely not a ‘double agent’, even though he has frequently been called that.

One reason that this distinction is so important is that nearly all the so-called ‘double agents’ utilized by the British in the run-up to OVERLORD had not been ‘turned’. Most of them had infiltrated the Abwehr under false pretences, and then made their true allegiance known when they arrived in Britain. The exception was TATE, who had to be threatened, and kept under very close control until he underwent a real ideological conversion, his wireless equipment being operated by an MI5 impersonator borrowed from Army Signals. He was not completely trusted even in the summer of 1943, although MI5 believed that, if he had tried to escape to Germany, his previous minders would have killed him instantly, while he would have blown the whole XX Operation.

Problems experienced with other German spies provide evidence of the tradecraft challenges that MI5 faced. SUMMER had to be incarcerated and isolated after he attempted to escape. When Oswald Job, on an Abwehr mission to deliver money to DRAGONFLY, confessed, he was briefly considered for a XX role, but then had to be prosecuted – and executed. DRAGONFLY‘s operation had to be terminated because of the connection and exposure. Yet those persons who passed the tests were strictly not ‘controlled enemy agents’ either, since only the Abwehr believed that they were true Nazi agents working for the German intelligence service (and not all Abwehr officers agreed with that, as it happened.)

In a CIA review of Masterman’s Doublecross System in 1974, A. V. Knobelspiesse tried to clarify matters by explaining that the British actually maintained four categories of double agents in World War 2: a) the classic double, who might have been in contact with multiple agencies, and thus had to take control of his own operation; b) the double agent who was not in personal contact with the enemy service, but communicated solely through writing or wireless; c) the penetration agent, a variety of ‘double’ who worked exclusively against other intelligence services to gain information; and d) the special agent, a double used solely for planting (dis)information on the enemy, a ‘feeder’.

Yet this is still a muddle. The penetration agent is not a variety of a ‘double agent’, even though he or she may be a gross deceiver. In Category B, impersonation (of activity on a wireless set) was a critical ploy – used by the Abwehr to good effect, too, or sometimes by forcing the operator to transmit under fear of torture or death. (SOE’s Gilbert Norman, aka Archambauld, notoriously agreed to do so, but his security check, the technique for showing he was transmitting under pressure, was ignored by SOE in London, and he capitulated in despair.) Category D appears to be different from Category B by representing the fact of personal contact with the enemy, but it unfortunately uses the terminological preferences of Colonel Bevan, the head of the London Controlling Section, for classifying MI5’s ‘double agents’ (as I have reported before).

If an agent could reliably be deployed to deliver information to the enemy in person (such as Dusan Popov, aka Tricycle), he was not a ‘double’. Those French agents who were captured and threatened by the Nazis (with family members perhaps held hostage), and then reported on their comrades (such as Roger Bardet), however we might sympathize with their plight, were traitors, not double agents. Moreover, agents who had been identified – but not ‘turned’ – could be fed disinformation (‘chicken-feed’, or ‘barium meals’) if it suited the authorities to maintain them in place, rather than arresting them and thus taking them out of action. That was a completely different aspect of tradecraft. Throughout the archives of MI5’s B1a, officers such as ‘Tar’ Robertson stress, however, that, if the unit cannot control a potential ‘double agent’, or implicitly trust his or her patriotism, such a character should not be used for deception purposes.

The confusion has persevered: Nigel West’s Historical Dictionary of WWII Intelligence (2008) defines a double agent in the following terms: “An agent working for one organization may be said to have been turned into a ‘double agent’ when he or she accepts recruitment from an adversary and then knowingly supplies the original employer with false information.” This would appear to resemble Category D, but how the subject ‘knows’ whether the information being passed on is false or not is not explained. No wonder the publishers’ writers of blurbs for books on intelligence are confused.

Thus the actions and lore of the XX Committee had ramifications that went far beyond D-Day, and the notion that managing ‘double agents’ was simply another ruse out of the counter-intelligence playbook took hold, as if it were similar to the process of ‘rounding up the usual suspects’ or ‘bringing on the empty horses’. According to some accounts, James Angleton of the OSS/CIA became excited about the possibilities of passing disinformation to the Soviets after working closely with Kim Philby – but, who knows, perhaps Philby misled him deliberately in getting him to think that such ploys could be used advantageously in that fashion?

Histories of the CIA routinely misrepresent the lessons from the ‘successes’ of the XX Committee. Guy Liddell’s Diaries are littered with examples of Admiral Godfrey of Naval Intelligence dropping by after the war to chat to him about the Double-Cross Operation, in the hope that similar techniques might be used against the Russians. (But Liddell knew better.) In one of the more plausible passages in Spycatcher, Peter Wright describes the ridiculous attempts by MI5’s Graham Mitchell, in D Division, to emulate the wartime XX exploits with Russians and eastern European émigrés (pp 120-121). Michael Howard foolishly wrote a letter to the Times claiming that Anthony Blunt had been more usefully exploited (instead of being prosecuted) by letting him pass disinformation to Moscow. And so on.

M. R. D. Foot’s definition above is simply foolish, and the bizarre examples in his short entry show a mixture of traitorousness, duplicity, and misbegotten confidence in an informer. The later definitions emanating from the CIA and the KGB, however, start to show a much more distinct realism about the matter. The observation by Miles Copeland (who was charged with keeping a close eye on Philby in Beirut) probably reflects some retrospective imagination, but by the 1960s, the realities of dealing at arm’s length with agents who had been recruited with the intention of spreading disinformation to the Soviets had set in. On the other hand, the CIA field guide definition, more complex as it is, implies that the intelligence agency accurately knows what the ‘double agent’ is doing when he or she withholds information, or passes on disinformation. Since such transactions carry on unsupervised, how could the agency ever know whether its agent was drifting into the territory of peddler, fabricator, or, as is commonly defined, ‘trader’? And the CIA’s own officers continue to misrepresent policy. The CIA appointed an academic, Dr. David Robarge, to the position of Chief Historian in 2005, but his pronouncements since, in articles and interviews, shows that he also misunderstands how the Double-Cross Operation worked in WWII, and he continues to labour under the misapprehension that ‘turned’ agents become the ‘owned’ emissaries of the agency that turned them. [See, for instance, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4pin7eqFxQg : this topic merits a deeper investigation at another time.]

The KGB definition is much more hard-headed: the double agent is probably duping both his recruiters, and is inherently untrustworthy. When Kim Philby landed up in Moscow, he was prevented, despite his long track-record in spilling reams of information to the Kremlin, from seeing any secret information about KGB assets lest he somehow leak them back to MI6 in London. No one should be trusted.

The rules for handling agents with shifting loyalties might be summarized as follows:

1) Any agent who too readily switches his or her ideological or patriotic affiliations, or is easily bribable, should be distrusted, as he or she will probably betray any new allegiance;

2) Any agent who is persuaded to ‘turn’ through torture or by other threats will be resentful and vengeful, and will need to be watched carefully;

3) Any ‘turned’ agent deployed to carry disinformation to the enemy will need to be controlled closely, and unmonitored contact with the enemy should be avoided;

4) Any agent used for deception purposes should not know what is disinformation, lest he or she betray secrets under torture;

5) Any agent who claims to have escaped from the custody of an enemy organization should be very stringently interrogated;

6) Any agent detected to be working on behalf of more than one intelligence agency should be wound down, at a pace that fits the situation;

7) Agents on home territory who have to be ‘retired’ because of exposure or risks to other assets will have to be isolated, or otherwise severely dealt with;

8) Agents on foreign territory suspected of having being betrayed, or having been suborned by the enemy, should be isolated immediately, and contacts broken off.

It all reinforces the requirement for individual agents to be isolated, and not be aware of the broader connections of the ‘ring’. When Goronwy Rees ‘defected’ after the signing of the Nazi-Soviet pact, Guy Burgess wanted him killed because he knew too much. When Burgess and Maclean absconded, suspicions over Philby grew because he had harboured Burgess in Washington. The Prosper circuit was destroyed partly because it borrowed wireless-operators from other networks, and members socialised too freely. Yet espionage is a lonely job, and contacts with occupational ‘colleagues’ are often a big boost for morale.

Déricourt’s Possible Status?

To return to Déricourt. When he arrived in the UK in September 1942, he could have had a variety of statuses, as a potential asset of British Intelligence, and a possible agent sent over by the Abwehr, or possibly by the Sicherheitsdienst (although the latter organization had no known procedures for infiltrating agents to Britain). Given that the XX Operation was just maturing at that time, it is educational to compare his status and profile with those of renowned real and potential ‘double-cross’ agents. So what was he?

Was he like TATE (Wulf Schmidt), who was a diehard Nazi, but who agreed to act as a controlled agent under threat of death, but eventually became an anti-Nazi because of what he learned about life in Britain?

Was he like SUMMER (Gósta Caroli), another diehard Nazi, who similarly agreed to act as a controlled agent, but tried to escape when he had the opportunity, and thus had to be incarcerated?

Was he like TRICYCLE (Dusan Popov), who claimed that he had got himself recruited by the Abwehr through deception, but whose true loyalties were to the Allies, and he was confidently trusted?

Was he like TREASURE (Lily Sergueiev), who similarly claimed that she had got herself recruited by the Abwehr, and was trusted until she showed alarming signs of torn allegiance and affront, and had to be dropped?

Was he like BRUTUS (Roman Garby-Czerniawski), who narrated a suspicious tale of escaping from Nazi captivity, and of having done a deal with the Abwehr, but whose ultimate loyalty was trusted?

Was he like ZIGZAG (Eddie Chapman), who was completely amoral, and developed such a web of duplicity that his only loyalty was to his personal survival?

When Déricourt arrived in Britain, he could have:

i) admitted that he had been recruited as a German agent, but it had been a bluff; or

ii) admitted that he had been recruited as a German agent, but under pressure, or for other reasons, agreed to switch his allegiance;

iii) concealed the fact that he had associations with the Sicherheitsdienst, and stated his eagerness to help the Allied cause;

iv) admitted his contacts with the Luftwaffe, but minimized their importance, and likewise declared his loyalty to the Allied cause;

v) arrived as an adventurer, with a dubious past, and a fear that he might be incarcerated, with some vague ambition to help the war effort, and dissembled about part of his experiences.

It is necessary to inspect the archival material closely to come to any confident conclusion. But first, an aside on MI5.

The Fragmentation of MI5

Regular coldspur readers will probably be aware that I deplore heavy use of the passive voice in historical accounts, or vagueness about actors/perpetrators. (Forgive me where I have transgressed.) Thus I consider expressions like ‘it was believed that’, or even ‘the Foreign Office thought’ as intolerably lazy and imprecise. If a formal statement was made by a senior official, he or she should be identified, and the statement dated. If there is no archival record, or trace of memoir or diary, extreme caution should be used before echoing what a previous historian may have written. It is very imprecise to make vague generalisations about departmental policy in British government departments. The whole character of a pluralist democracy implied that multiple opinions competed for attention, and the battles between, say, the Foreign Office and the General Staff, or MI5 and MI6, or SOE and practically everyone else, were a permanent fixture of the political discourse. And such divisions existed within institutions, as well, such as the tensions between F Section of SOE (i.e. Buckmaster and Atkins primarily) and those officers in charge (notably Gubbins, Sporborg, Boyle and Senter, but probably not Hambro, who was apparently kept in the dark), with Bodington as a devious intermediary.

I suggest that the role that MI5 played in the drama concerning Déricourt’s recruitment may have been oversimplified by both Robert Marshall and Patrick Marnham. MI5, the agency overall responsible for vetting arrivals on British shores, was not a monolith, and was divided, conventionally by organization, and more subtly, by hierarchy. That means that any statement about what MI5 said or did has to be qualified by identifying which officer was responsible. The reason for this is that senior members of MI5 sometimes concealed information from the lower-level officers. I explained how this happened in my analysis of Agent Sonia, where officers such as Hollis, White and Liddell were obviously colluding with Dansey in MI6 over Sonia’s entry to Britain, but not informing the ‘grunts’ on the ground (e.g. Michael Serpell and Milicent Bagot) about what was going on, to their continued frustration.

Moreover, MI5 was a muddle, even after David Petrie’s reorganization of July 1941. It comprised a very flat structure, with many apparently overlapping functions. Dozens of names arise in the Déricourt archive, and it is important to track what each individual role was. In early 1943, when it came to vetting arrivals to Britain, Section B1D, under Baxter, held overall responsibility for the LRC (also known as the Royal Victorian Patriotic School, RVPS), but the officers who carried out the interrogations (some of whom had been recruited from MI6), such as Beaumont (France) and Ramsbotham (USA), worked in E Division, under Brooke Booth, in E1A. Jo Archer, who was responsible for liaising with the Air Ministry and BOAC, led D3, in Allen’s D Division, with Sargant reporting to him with focus on the Air Ministry. Security in the ports was managed by Archer’s colleague Adam (D4), with Mars, responsible for Travel Control and Permits, working for Adam. Yet again, another Division (C) was involved with credentials for the Admiralty and Air Force, where Sams and Osborn (C3) took on that role. Robertson managed Special Agents in B1A; Stephens was responsible for Camp020 & 020R, in B1E; Hart for Special Sources Case Officers in B1B.

The major relevant sections of this complex organization can be represented as follows:

A Division: Administration and Registry (Butler)

B Division: Espionage (Liddell; deputy White)

B1 (Espionage)

B1A (Special Agents: Robertson)

B1B (Special Sources Case Officers: Hart)

B1C (Sabotage, Inventions & Technical: Rothschild)

B1D (London Reception Centre: Baxter)

B1E (Camp 020 & 020R: Stephens)

B3A (Censorship: Bird)

B4A (Escaped Prisoners of War & Evaders: J. R. White)

C Division: Examination of Credentials (Allen)

C2 (Military Credentials: Stone & Johnson)

C3 (Credentials for Admiralty, Air Force, etc.: Sams)

D Division: Services, Factory & Port Security, Travel Control (Allen)

D3 (Air Ministry, etc, : Archer)

D3A (Liaison with Air Ministry: Sargant)

D4 (Security Control at Ports: Adam)

D4A (Travel Control & Permits: Mars)

E Division: Alien Control (Brooke Booth; assistant Younger)

E1 (Western Europe, etc,)

E1A (French: Beaumont; USA: Ramsbotham)

E1B (Seamen: Cheney)

E2 (Eastern Europe: Alley)

E3 (Swiss & Swedes: Johnston)

E4 (AWS Permits: Ryder)

E5 (Germans & Austrians, Camp Administration & Intelligence: Denniston)

E6 (Italians: Roskill)

F Division: Subversive Activities (Hollis)

F1 (Internal Security in H.M. Forces: Alexander)

F2 (Communism & Left Wing Movements: Clarke & Shillito)

F3 (Fascist movements, Pacifists, etc.: Shelford)

The point is that most of these units turn up in the MI5 Déricourt files (KV 2/1131 & 2/1132), and they all have different agendas, and varying access to information. Thus, given the unwieldy structures, expecting clear and prompt reaction to events in Déricourt’s case was not reasonable. Those circumstances help to explain the following narrative, where officers like Beaumont struggle, showing complete ignorance of what was going on, while a high-up like Archer is revealed to be much more familiar with the chain of events over Déricourt’s vetting and recruitment, but then has to resort to clumsy evasions. It displays an astounding level of ineffectiveness in management and leadership, where senior officers in MI6, SOE and MI5 were spending far more time deceiving their colleagues than they were frustrating the enemy.

Déricourt’s Recruitment by SOE

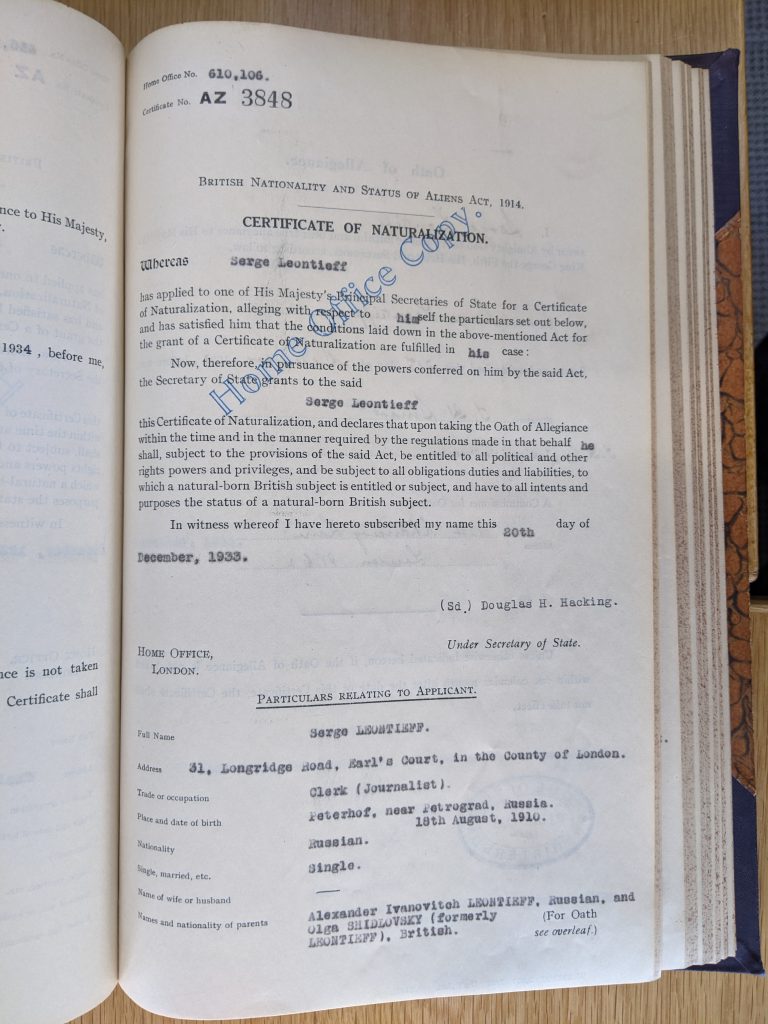

To recapitulate: Déricourt and Doulet had arrived in Dourock, near Glasgow, on September 8, 1942, on the Llanstephan Castle. They had come from Gibraltar, and their egress from southern France had been approved by MI6, which controlled the MI9 escape lines, in this case the so-called PAT line. Documentation on their interrogation in Scotland is practically non-existent, but they did not arrive at the LRC until September 15 – itself a puzzlingly long interval. Doulet (but not Déricourt) was on record that he had claimed on his arrival at Dourock that he was ‘on special mission, engaged by British Overseas Airways’. I now reconstruct the sequence of events between September 1942 and January 1943.

First, they had to be processed and checked out. Beaumont (who is probably not the same-named MI6 officer who, ‘speaking French with a Slav accent’, facilitated the transfer of the two Frenchmen on to the PAT line in Marseilles) carried out the initial interrogations, and confirmed that the stories of Déricourt and Doulet corresponded (29.9.42). (It appears that Déricourt did not declare his contacts with German intelligence to Beaumont: if he did make such an admission, as Marshall cites Lord Lansdowne as claiming, it must have been to the immigration officers when he landed. Yet that information should have been passed to D4.) On learning of their request to join BOAC (30.9.42), Brown of the Air Ministry approached Sargant (D3A) to have the two pilots vetted. D3A requested Beaumont to check out Doulet and Déricourt again by approaching the Free French (9.10.42). Beaumont apparently did so, but nothing happened for a week, at which time Brown pressed Sargant for a reply.

A keen interest in all arriving Frenchmen was shown by the BCRA (Bureau de Renseignement et d’Action), the Free French Intelligence Service, who claimed priority access to such persons. What is noteworthy about Sargant’s request is the fact that Dewavrin, aka Colonel Passy, of BRCA, had welcomed Déricourt and Doulet when they arrived at Euston Station on September 10. This should have been a controversial encounter, since the Free French claimed rights on the recruitment of any native French citizen, but, in this case, they let both pilots go. Marcel Ruby’s book on SOE’s F Section states that those Frenchmen who were out of sympathy with the Gaullist movement were sometimes encouraged to join F Section, as it offered superior training and access to equipment and flights, and he offers testimony from non-Gaullist Frenchmen who were able to take advantage of such policies. Thus the frequently expressed description of vehement animosity between Section F and the Free French may not be as true as M. R. D. Foot made out.

Clearly, Claude Dansey, according to some accounts (e.g. Ruby) a close colleague and supporter of the Free French but to others (such as Cecil) a sworn enemy, had alerted the BCRA to the arrival of the pair, but had kept the news from those responsible for carrying out the investigation. What motive Dansey had in introducing the two so openly is superficially bewildering, since the pilots were later adamant that the Free French not be informed of their exploits, and the Free French in turn, now aware of their presence and ambitions, tried to warn the British authorities not to use them. That might have been a covering manœuvre, however. After the war, however, Déricourt was arrested at Croydon Airport for attempting to smuggle out gold nuggets and currency, purportedly on behalf of some shady ex-BCRA officers, so he probably maintained his contacts.

The investigation continued haphazardly. On 17.10.42, de Lazlo of the Air Ministry reported to Broad, of the BOAC in Bristol, that the Free French wanted nothing to do with Déricourt and Doulet – not an astounding revelation, from what we know now, of course. This apparently alarmed Beaumont. He echoed the fact that the two might have been offered jobs by Forbes, but raised the question that, given that promise by British Airways about which the Germans would have learned, the pair might have been compromised, and sent over as agents. Consequently (20.10.42), he told Sargant that MI5 could in no way guarantee them from a security point of view, and, at the same time, contacted Ramsbotham (responsible for the USA) to follow up the contacts with the US Consulate, so that they could establish from Donaldson of the US Consulate in Marseilles how he had assessed the pilots’ integrity and reliability.

Sargant informed the Air Ministry of Beaumont’s concerns, which in turn alarmed Brown. Squadron-Leader Chaney became involved, and looked into Forbes’ offer. On 27.10.42, Chaney was able to confirm that Forbes had indeed offered both men contracts (a claim that would later be undermined), pointed out that the LRC had given give them a favourable report, and showed concern that the men might challenge any interference with their assignments at a ‘high level’. BOAC had already placed the two on subsistence. Yet Sargant was insistent (5.11.42) that the two were a security risk. Beaumont’s judgment was now under scrutiny, as the Foreign Office had become involved. Doulet had approached the Under-Secretary of State, Simpson, querying what the delay was about, so Simpson contacted Beaumont directly (24.11.42). On 30.11.42, Beaumont boldly defended his position, but suggested, as a compromise, that the two be employed some distance away, in the Middle or Far East. On 3.12.42, Ramsbotham presented Donaldson’s confirmation of their recruitment, and of the fact that they had contacted the British ‘underground’, dated 16.11.42. On that date, Déricourt was at RAF Tempsford, receiving training.

What this whole rigmarole needed, apparently, was for others to get involved. At this stage, on 4.12.42, Jo Archer (D3, to whom Sargant reported, and who was the husband of the eminent Soviet expert Jane Sissmore, now in MI6) made an entry to the stage, with some very odd observations, made in writing to Chappell at the Air Ministry. Chaney was still investigating with Forbes the pilots’ assertions about job offers; Archer doubted that they were offered contracts, and stated rather enigmatically that ‘neither of them claimed this’. He was suspicious of Doulet’s claims from Syria of wanting to return to Vichy France to settle personal matters, and he drew attention to the gap in dates between their ‘repatriation’ and application to the US Consul in Marseilles. He thus doubted the loyalty of these Vichy men wanting to fight Germans, and indicated that they were more interested in a ‘fat salary’. Nevertheless, he ventured the opinion that BOAC would skate over all objections, and recruit them.

What was Archer doing here? Trying to lay a false trail of due diligence, but pointing inquirers away from SOE? In any case, some long-winded discussions took place between Beaumont, Sargant and de Laszlo as to where BOAC could safely employ the pair. Simpson was involved again, and wrote on 22.12.42 that Déricourt and Doulet had received a (positive) response from BOAC on 2.10.42. The case appeared to be winding down, and Chaney reported to his boss at the Air Ministry, Wing-Commander Calvert, on 23.12.42 that Forbes had confirmed that Doulet was among those interviewed, and that Maxwell (the regional BOAC director) had said that ‘if any Air France pilots turned up in Lisbon, BOAC would be willing to employ them, subject to security’. But he added that, as early as 23.9.42, Forbes had confirmed that he had promised employment to Doulet only, if he were to reach Lisbon, following with ‘None of the others who were given offers have appeared in UK’. He had apparently not been told of Déricourt’s presence in Britain.

So had Archer been sitting on the information from Forbes for three months, and keeping the facts from Beaumont? It certainly looks like it. Yet the responsibility was thrust back on him: on 23.12.42, Calvert wrote to Archer that the Ministry proposed not to approve the employment of either pilot unless Archer were satisfied that the suspicions over security has been removed. By the last day of the year, Archer had apparently discussed the case with the Free French, who had also magically changed their minds. He found a lame excuse. “The assassination of Darlan allows MI5 to look more favourably on them from the security point of view,” he wrote, “although there is still some risk”. Why the assassination of a Vichyite (possibly through the machinations of SOE) who had switched his allegiance lessened any possible exposure in sending the pilots abroad was not explained.

Matters begin to get even more bizarre. The same day, Archer decided to give Beaumont a rebuke, telling him he should not give advice on air interests without clearing it with him. (Then what had Beaumont been doing, working through the proper channels with Sargant?) On 1.1.43, Roddam of the Ministry of Labour informed Osborn of MI5 that Déricourt and Doulet had been rejected by BOAC for ‘service’ reasons. The very next day, Beaumont, having spoken to de Laszlo, noted that the pilots had both gained jobs with BOAC in the Middle East, and Doulet’s application for an exit permit to North Africa was soon approved. Meanwhile, he reported that Déricourt had disappeared, noting he was going to the USA ‘on a mission’, news that rather peeved BOAC, as they had been paying him. Osborn, Roddam, Simpson and Beaumont all seemed to be under the impression that both pilots were being sent to the Middle East.

This inept performance could surely not be a charade to confuse the historians, for, even when an officer at SOE showed interest in Déricourt’s status, Beaumont continued the line. He must soon afterwards have been approached by SOE. On 21.1.43, the same day, in fact, on which Déricourt parachuted into France, Beaumont, after speaking to Flight-Lieutenant Park of SOE *, in writing confirmed to Park Déricourt’s statement that he was leaving on a mission to the USA. It was not until 30.4.43 (when stronger suspicions about Déricourt were being raised) that Beaumont referred to a report from the Free French that had unaccountably been delayed in reaching him. He then relayed the disturbing news to Park that the Gestapo might have been interested in Déricourt. The report, tagged as 24b, has been weeded from the archive, but it may have been contemporaneous with the Free Frenchman Bloch’s complaints about Doulet, from 8.2.43. So it was not until the doubts started to emerge from SOE itself that Beaumont understood where Déricourt had gone.

[* Despite the oft-cited assertion that SOE’s existence was not known to many persons, and that SOE officers were supposed to refer to it as the ‘Inter-Services Research Bureau’, Beaumont’s letter of 21.1.43 at 34B in KV 2/1131-3 is addressed to ‘Flight Lieutenant J. H. Park, S.O.E.’ Intriguingly, the signature on Park’s response seems to be ‘H. E. Park’. This person would not appear to be a relative of Daphne Park, the famed MI6 officer who started her career as a FANY with SOE in 1943 or 1944. It is probable that Vera Atkins was writing to Beaumont under an alias. In Sara Helms’s A Life in Secrets, Atkins’s assistant who shepherds in SOE candidates for interview is described as a man named Park. Atkins later claimed, moreover, that she held instinctive suspicions about Déricourt. As the intelligence officer in F Section, she would have been the obvious candidate to communicate with Beaumont about him, and might have been keen to conceal her identity as she was not only a woman, but lacked British citizenship at that time, having been born a Romanian with the Jewish name of Rosenberg. Yet the exchange confirms one very important fact: at the time of Déricourt’s first excursion into France, an influential SOE officer was concerned that he was a risk.]

It is clear that the lower-level Free French officers had got wind of the true disposition of at least one of the two pilots early in 1943. When Bloch learned of Doulet’s imminent departure for North Africa on 8.2.43, he was incensed, and wrote to Beaumont that he should be recalled immediately. (Another ‘grunt’, perhaps, being misled by his superiors. Yet Patrick Marnham has pointed out to me how the disreputable behaviour of Déricourt in London, before he took up his official duties, attracted the scorn of the BCRA, and that Doulet was probably tarred by the same brush.) Archer’s flimsy argument of 31.1.42 now looks very deceitful. Beaumont responded that Doulet did not work for the British authorities, but for BOAC, a commercial enterprise. He claimed that he did not know whether Doulet had left the country yet. Thus at this time Bloch may have written an uncomfortable memorandum about Déricourt as well, no doubt to an officer at a higher level than Beaumont, and the latter considered it too sensitive to be given to Beaumont immediately.

All this would be later shown in perspective when Geoffrey Wethered carried out a detailed investigation into Déricourt in March 1944. When writing to the Regional Security Liaison Officer Gerald Glover on 11.3.44, trying to find employment for Déricourt and his wife, who were installed at a hotel in Stratford-upon-Avon, Wethered wrote that Lemaire (the cover name for Déricourt) ‘after being cleared at the LRC was recruited by SOE’. He does not give a precise date, but it is obvious that the high-ups all knew that Déricourt had been taken on by SOE, while Beaumont and other lower-level officers in MI5 (as well as important figures in the Air Ministry and the Foreign Office and the Home Office) were under the impression through December and January that he was working for BOAC. And even the suspicious Park of SOE did not counter to Beaumont the fiction that Déricourt had been sent to the United States. On 23.1.43 he (or she) had thanked Beaumont for his BOAC-oriented report.

Yet the most extraordinary item is the proof of Archer’s connivance at what was going on. In a statement he made in a report to Wethered dated 9.2.44, he relayed what BOAC knew about Déricourt: “Déricourt called at the BOAC office in Victoria on 9.9.42 and said he had been offered a secret mission at the War Office.” In other words, several days before he and Doulet arrived at the LRC, Déricourt had been signed up by MI6. Moreover, according to M. R. D. Foot, Déricourt and Doulet were welcomed by Dewavrin at St. Pancras Station on September 10, which would suggest that Déricourt had enjoyed his successful interview with MI6 (and Doulet his corresponding session with BOAC) before meeting the Free French. In any case, it is staggering that, in a time of war, so much time and effort should have been wasted chasing false leads and creating paperwork because of a perpetration of lies within the Security Service, and beyond.

Robert Marshall describes some other intriguing events from this period. He tells how the pair arranged, by telephone a rendezvous in Piccadilly Circus three times, in October and November, and that, some time after this, they enjoyed a re-encounter at a ‘luxurious flat that was shared by the two Belgians with whom they had sailed on the Tarana’. In this setting, a British intelligence officer named FRANCES asked Doulet whether he wanted to perform secret work in France. Doulet declined, but assumed that Déricourt had already been recruited by FRANCES’s organization. Déricourt later warned Doulet to keep silent over the meeting, and his mission. This narrative is based on what Doulet told Marshall, but the meeting is not dated, and cannot be verified. Moreover, some aspects of Doulet’s story must be questioned. The archive indicates that they were staying at the same address until November 2, when Doulet moved to Charlwood Street, and Dericourt to Jermyn Street. And MI5 were intercepting Déricourt’s mail. He received a very coy letter from Doulet (in which Doulet addresses his friend with the intimate ‘tu’) on January 2, 1943, which reads as if it is setting a false trail.

I shall analyze in detail the events of early 1943, when suspicions about Déricourt began to be cast, up to the denunciations later in the year, and Déricourt’s recall in early 1944, another time. It is a continuation of the whole sordid business described above, replete with lost reports, mistaken identity, overlooked messages and phony stories, indicating the great discomfort those in the know experienced when troubling questions began to be asked about Déricourt’s recruitment. But the important conclusion appears to be that Déricourt was prepared as to how he should behave before he arrived in Scotland, and MI6/SOE were ready to pounce as soon as he arrived.

The Passage to Gibraltar

If Déricourt was indeed prepared for his interrogators in the United Kingdom, how did it happen? I drew attention, in corresponding with Robert Marshall several weeks ago, to the fact that Dansey’s shock on learning that Doulet and Déricourt had just arrived in Gibraltar sounded contrived and unconvincing to me. I wrote:

All The King’s Men makes it quite clear that MI6 must have learned about Doulet & Déricourt from Donaldson, Langley and Garrow when they were in Marseilles, so Dansey’s apparent ignorance of who they were when they reached Gibraltar is quite absurd. You write that Garrow paid a ‘surprise visit’ to Déricourt in May 1942, suggesting he had been directed to make inquiries – about Borrie. Then is it not possible that Dansey at that time decided to have Bodington sent out to contact his old friend in person? The justification for Bodington’s presence in southern France was that he was there to assess Carte (and granting that network a substance it didn’t have could have been another Dansey coup), but it is difficult to imagine that he would go all that way and NOT see Déricourt, given the exchanges that had gone on.

If that were true, it would explain why Déricourt thought he had a good shot at getting through any vetting, and it would confirm that Dansey’s expostulations were a sham, for the record.

[Notes: ‘Carte’ was another SOE network that was later discovered to have been betrayed, infiltrated by Hugo Bleicher of the Abwehr. Mathilde Carré had betrayed the Interallié network and become Bleicher’s mistress at the end of 1941.]

Marshall responded to me as follows:

“The gentleman I dealt with over a year or so was Christopher Woods [the SOE Adviser]. At times keen and eager to help with information, but we often hit a road block when he ran up against his proprietorial limitations.

My reading of links between MI6 and HD is that there were fragmented contacts prior to his departure, none of which would necessarily have filtered up to Dansey. Dansey’s query to MI6 Gibraltar was, I believe, quite genuine. Who the **** are these two?

It’s possible Bodington may have contacted HD while he was in and around the South of France, but that assumes he knew where he was, or how to reach out to him. HD claimed he did Intelligence work before the war; but that doesn’t make it so.”

My point was based on the firm understanding that Dansey maintained a tight rein over the so-called ‘PAT’ Escape Line, managed by MI9 (a unit also controlled by Dansey), and that he would have had to approve any unusual candidates before they were accepted in Marseilles, or Geneva, or points in between. Indeed, Marshall himself writes (p 61): “A great deal of MI9’s traffic was going to pass through Vichy France, which ideally meant Marseilles. Dansey had the contacts and the resources to set up a top-level escape service from Marseilles, which he offered to do and then put it at MI9’s disposal. In return, MI9 had to accept Dansey’s remote control, which he effected through his representative, the ex-Coldstream Guardsman James Langley.” Marshall later describes the persistent efforts by the two pilots to push their requests through H. M. Donaldson at the US Consulate. “By this stage, London was very familiar with the names Déricourt and Doulet”, he continues (p 69), and Ian Garrow, who manned the escape line, then paid a surprise visit to Déricourt. In a comment attributed to the Foreign Office adviser, Marshall presents the outcome as follows: “Finally Langley relented and in what he described as a ‘quid-pro-quo for help the Americans had given us’ agreed to put Déricourt and Doulet on the escape line’. But what advantage or benefit did the American get from the decision, apart from taking an annoying pair off their hands? Yet Langley followed up by telling the eponymous ‘Pat’ (O’Leary – actually Albert Guérisse) that the pair were to be despatched to London ‘by the quickest possible means’.

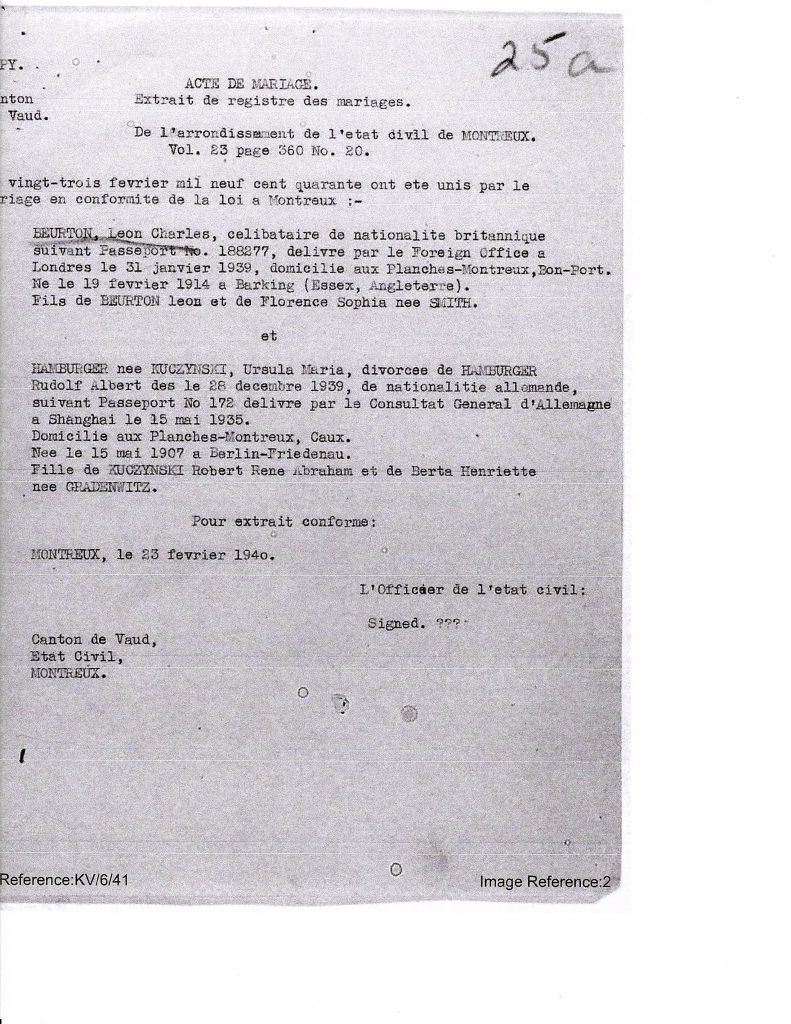

A further indication that MI6 had approved the escape up front appears in the activities of other MI6/SOE personnel at the time. On July 30, an SOE French team (i.e. ‘F’, not Free French, ‘RF’) left Gibraltar and landed at Antibes on the felucca Seawolf. The party consisted of Bodington (Déricourt’s pre-war friend, and now assistant to Buckmaster in F Section), Frager, Despaigne, and Rudellat. Bodington was on a mission to investigate the strength of the Carte network that had been constituted from the remnants of the betrayed Interallié circuit. * On August 31, another felucca, the Seadog, left Cape D’Ali (near Monte Carlo): on it had boarded Bodington, alongside Buchowski and Diamant-Berger. Exactly in the middle of the month, the disguised trawler, the SS Tarana, had picked up eight passengers at Canet Plage, near Narbonne. The passengers were Déricourt and Doulet, accompanied by P/O Derrick Perdue, Sgt. Jack Missledene, Leoni Savinos and his wife, and a Serbian officer. One was thus unnamed. The Tarana then sailed to a cove between Agde and Narbonne, where it picked up six agents, including some from a BCRA (Free French intelligence) mission, with the last described as ‘Pilot André Simon’.

[* I thank ‘Marcel Treville’ and his extraordinary website at http://plan-sussex-1944.net/ for much of this information.]

André Simon was another man working for SOE (Maurice Buckmaster refers to him in his interview available at the Imperial War Museum), a gentleman who, as the Foreign Office adviser informed Marshall, was ‘probably the individual who brought Déricourt’s name to SOE’s attention.’ Several accounts show André Simon active in southern France at this time, having escaped from the Vichy authorities. Yet his identity must be pinned down. Jean Overton Fuller, in Double Webs, citing F.F.E. Yeo-Thomas of RF Section, indicates that Déricourt was introduced and guided by the wine-merchant, Andre Simon père. Robert Marshall refers to an André Simon with whom Déricourt stayed in London during his fleeting visit in July 1943, indicating that he was the son of the well-known wine-merchant (born in 1877), while possibly merging the identities of the two. Foot describes the SOE agent Simon the same way, while Patrick Marnham presents him as another MI6 ‘mole’ in SOE. Simon fils was born in 1906, and his details can be seen at https://www.specialforcesroh.com/index.php?threads/simon-andre-louis-ernest-h.31794/. Bodington’s presence may have been coincidental, of course, but it is difficult to explain otherwise. And, if there were BCRA officers on board, the intelligence would soon have reached de Gaulle’s ears. Overall, one might conclude from these events that, while MI6 had designs for Déricourt before the embarkation, the encounter with Simon solidified his recruitment by SOE.

In the version that Doulet later supplied Marshall, there were ten of them in the rowing-boat that took them to the trawler, with the eight passengers described as follows: ‘a navigator from a Wellington bomber, a Yugoslavian couple, two Belgian intelligence officers and an Englishman, whom Déricourt took to be from MI6.’ Yet, in listing the presumed MI6 officer (Simon), Doulet may have merged two pick-ups into one. Déricourt apparently became well acquainted with Simon at this time, but it is not clear whether this was an accidental encounter or not. And the BCRA would have been inevitably exposed to Déricourt, an event that may have prompted Dansey to pre-empt the situation when they all arrived in the United Kingdom. Moreover, Déricourt later misrepresented the whole business: he told his close friend and pilot Hugh Verity that he had escaped over the Pyrenees, and made contact with the British in Spain or Gibraltar.

By one of those extraordinary coincidences, on the morning I was writing the above paragraphs, a contact in the coldspur network alerted me to an article that reinforced my suspicion that Déricourt had been recruited (or at least ‘approached’ with the goal of recruitment) by MI6 before his escape. It appeared in the May 1986 issue of Encounter, and was written by James Rusbridger. (Rusbridger had been a courier for MI6, and was a frequent critic of intelligence agencies. He was discovered asphyxiated in 1994, an apparent suicide.) Rusbridger came to the conclusion that Déricourt had been recruited earlier, in France, although he had not been able to inspect the KV files at Kew. He did, however, probably enjoy access to the same sources that Robert Marshall exploited, and benefitted from speaking to Marshall himself.

Marshall has informed me that he worked alongside Rusbridger in the early days of the Timewatch project, commenting: “He, like others, was convinced HD had been recruited by MI6 long before he came to the UK. It’s a tantalising prospect, but doesn’t really (I think) illuminate much.” Marshall thus minimises the importance of this theory, but, since it is on the surface in direct opposition to what Marnham proposes – namely that Déricourt was first recruited by the SD, and that British Intelligence had nothing to do with him until he arrived in London – it needs to be inspected closely. The evidence for SIS’s interest in him in France is, in my mind, stronger than any that has been presented as a serious approach by the Sicherheitsdienst.

Rusbridger thus had to sidestep the many deceptions of Maurice Buckmaster and the Foreign Office adviser, while inferring from the open evidence of Déricourt’s acquaintance with Bodington and Boemelburg, and the approval of his and Doulet’s passage on the MI9 escape-line, that Déricourt was already considered a sign-up with a murky British service. Where Rusbridger had exclusive access, however, may have been to the log-books and private papers in the apartment of Déricourt’s widow (who died early in 1985). Rusbridger claimed that Bodington had worked for MI6 (presumably in the Z organization) while he was working at Reuters in Paris, and had recruited Déricourt ‘because of his friendship with and work for Boemelburg’.

Unfortunately, Rusbridger does not provide a date for this recruitment, and muddies the waters by writing, almost in the same breath, that ‘Déricourt had already done some intelligence work for the SD; Boemelburg had him listed as V-Mann/48.’ Thus we are back to Square One, with the competition for Déricourt’s allegiance simply pushed back in time. The exact status of Déricourt as a ‘double-agent’ (something even the conspiracy-doubters such as Mark Seaman carelessly admit) remains highly dubious. To return to my question earlier: Was he originally a German agent whom the British thought they could trust, or was he an MI6 agent who was suborned by the Gestapo, exploiting their more casual interchanges with him from beforehand? Or was he perhaps simply an amoral wheeler-dealer who tried to play off both sides against each other, and get paid by both in the process, what the intelligence professionals call a ‘trader’? In any event, Rusbridger’s analysis would tend to endorse the view that Déricourt was not smoothly and unquestioningly ‘turned’ only when he arrived in London, and to reinforce the fact that the haste with which he was adopted could be explained by earlier negotiations. That would account for the way that senior MI5 officers had to be brought into the secret.

Of course, such a theory does not materially change the interpretation of whether Déricourt was put to work by Dansey to destroy the Prosper network, but it surely provides a more convincing explanation of the otherwise unaccountable events of 1942.

Déricourt’s True Status

So what is the evidence for establishing Déricourt’s loyalties? Déricourt did not have to come to the UK. (He had asked the Americans to exfiltrate him.) He sought out the opportunity, but not too eagerly, and developed a legend about flying experience that was mostly fabrication. He knew that MI6 was aware of his contacts with Boemelburg. According to All the King’s Men, he was concerned about MI6 discovering his lies, but he also admitted his German contacts immediately. He did not claim that his contacts were a bluff. Marshall has found no evidence that he had been recruited by the Germans by then. In the reconsideration of the cases enumerated above in Déricourt’s Possible Status, Case 1 should therefore be rejected.

War in the Shadows makes the claim that Case 2 was the explanation. “An SIS spotter at the LRC quickly identified Dericourt as a German agent and turned him.” But that has a ‘with one bound Jack was free’ ring about it. No one could have simply ‘turned’ a dedicated German agent in a single meeting, off one’s own bat. Moreover, as I stated earlier, Marnham’s claim that Déricourt was turned specifically assumes that he must have been a German agent when he arrived, and that the LRC knew that for sure. If Déricourt did admit to being a German agent, there is no evidence of it. Case 2 should be rejected.

Déricourt’s lack of concealment disqualifies Case 3. He did both: he admitted his contacts, AND expressed his willingness to help. Case 5 looks to be unlikely, as Bodington (and maybe others) knew about his past, and it would do him no good not to volunteer such information. Bodington would not have been able to conceal that experience completely. Thus Case 4 looks the most realistic option. As Marshall writes, ‘going to England was a risk he took’. Déricourt could have been incarcerated. So what was the attraction of going to the UK?

The explanation could be that his reception was wired. He had been in contact with MI6 in Marseille, where his potential was assessed, and Bodington could have been sent out to interview him, and prepare him. Bodington and Déricourt probably sailed on the same trawler from Narbonne to Gibraltar. Dansey was ready for him when he arrived in Gourock, and he was swiftly transferred to SOE after he arrived at the LRC. Thus a modified Case 4 fits the bill. He admitted the truth on matters that he knew MI6 would be familiar with, but dissembled on issues that his interrogators would struggle to verify, such as his flying experience. He may have been encouraged by the Sicherheitsdienst to attempt to get recruited by British Intelligence in the belief that he would probably be incarcerated, but was not given the official BOE-48 designation (and payments) until he succeeded in returning to France.

The Aftermath, and Research to Follow

This was really only the beginning of the Déricourt story, and I refer readers to War in the Shadows to learn the details of what happened next. Chapters 19 and 20 give an excellent investigative account of the actions of the next twelve months, and Marnham deftly and crisply critiques the ‘official’ account from M. R. D. Foot within his text. Yet I believe the events need to be described anew with a more precise context for Déricourt’s recruitment. I recapitulate the story here, while encouraging readers to turn to Marnham’s book for a fuller account.

In a nutshell, Déricourt quickly established a successful record as an aviation planner for SOE in the spring of 1943, although that achievement was quickly followed by the start of questions about his loyalty, based on what observers knew about his past and current contacts. This culminated in Suttill’s vague suspicions, voiced in May 1943, that his PROSPER circuit had been infiltrated, and the eventual betrayal of Francis Suttill, Gilbert Norman, his wireless operator, and Andrée Borrel, his courier. In the autumn of 1943, more vigorous denunciations came from Henri Frager (LOUBA) when that agent visited the United Kingdom. That resulted in some semi-earnest investigations by SOE and MI5 – during which several officers thought that GILBERT referred to Gilbert Norman (ARCHAMBAULD) – and eventually Déricourt’s recall. He was withdrawn from SOE, and had to chill his heels in Stratford-upon-Avon, living with his wife under the alias Lemaire. Nicolas Bodington was also ‘suspended’ from SOE for a few months, and sent out on political training, but was re-accepted in March 1944, and became a successful member of one of the Jedburgh teams, ultimately receiving an award for valour. Thereafter, matters subsided until the famous trial in 1948, where Bodington came out to Paris to rescue his friend under threat of capital punishment for aiding the enemy.

My assertion is that analysis hitherto has not focused enough on a) the vital aspects of intelligence tradecraft, and b) the military context, of the whole saga. The actions of the Chiefs of Staff in trying to harness resources among the hectic goings-on of 1943, and how SOE’s initiatives fitted into that campaign, merit a completely separate study. I present the following research questions (some semi-rhetorical) on intelligence matters that the series of events provokes:

* Why would the Germans have invested so much in Déricourt before he left for England, when they must have believed that there was a strong possibility that he would be interned?

* Given that the Germans must have known that MI6 knew about D’s association with them, why did they think it made sense to try to infiltrate him?

* Why did SOE accept Bodington’s assessment that the Carte organization was strong and reliable?

* Given that Dansey knew that MI5 would probably refuse to approve Déricourt’s recruitment as an agent, why did he persist in defying them, and how did he succeed?

* If SIS hoped to use Déricourt as an agent who could infiltrate the Sicherheitsdienst, what possible value could they derive from it that would compensate for the horrific security exposure it created?

* When SOE first got wind of the possibility that the Prosper network had been betrayed, why did they not consider closing it down, rather than increasing shipments and landings?

* When SOE received proof that Déricourt was showing private mail to the Sicherheitsdienst, why did they not recall him immediately, and close down the network?

* Why was Bodington allowed to fly out to Paris to investigate the PROSPER disaster, given how much he knew, and how dangerous it would have been if he had been captured and tortured?

* Why did Bodington stay in France for so long, and why has his story about tossing a coin with Agazarian for going to Suttill’s apartment been accepted as permissible behaviour?

* Why did the Germans not arrest Bodington, since they knew about his presence in the capital?

* Why was Bodington released from SOE at the time of Frager’s denunciation, and why was he re-recruited a few months later?

* Why did Senter and Wethered not act upon Bodington’s claim that there was a German spy within SOE?

* How could Senter and Wethered possibly have confused GILBERT (Déricourt) with Gilbert Norman (ARCHAMBAULD)?

* Why was Guy Liddell so laid-back about the whole security exposure, given the intensity of such matters in the run-up to D-Day?

* Why did the Germans not take any action when Déricourt did not return to French territory?

* Why did Bodington so readily claim, at Déricourt’s trial, that Déricourt’s contacts with the Germans had been approved?

* Why did Déricourt appear to believe that he was invulnerable?

Patrick Marnham has indeed addressed many of these questions in War in the Shadows, but in what I have to characterize as a rather dispersed fashion, and I find his anachronous (achronological?) approach to storytelling a little confusing. I plan to deliver a concerted analysis that ruthlessly exposes the intelligence failures implicit in the saga, and what the implications are. The questions are of course complementary to the issue already raised about the suggestions of betrayal of the PROSPER circuit as a deception policy to influence Stalin about the presence of ‘Second-Front’ activities. My agenda runs (provisionally, since I am dependent on the delivery of photographed archives) as follows: February 2022 – War Cabinet activities in 1943; March or April 2022 – Investigations into Déricourt, with a summing-up some time thereafter.

Postscript

I added a brief comment to last month’s bulletin, drawing attention to a chapter in Intelligence Studies in Britain and the US, edited by Christopher R. Moran and Christopher J. Murphy, and published by the Edinburgh University Press in 2013. Dr Kevin Jones had reminded me of this piece, titled Editing SOE in France, which I had mistakenly imagined was the same text that I had cited by Dr. Murphy from 2003, namely The Origins of SOE in France. It is a more thorough investigation, and exploits more fully the archival material available at CAB 103/570-573 (but not apparently the several files that follow this sequence).

While the narrative certainly reinforces the fact that M. R. D. Foot endured continuing struggles with an ever-growing number of bureaucrats and civil servants, it does not shed much radical new light on the pressures that affected his delivery. Yet two sentences caught my eye. An important meeting had been held on October 29, 1963, where a Norman Mott had played a leading role in the consideration of security issues that had been raised by Foot’s finished draft. Norman Mott had headed the SOE Liquidation Section (a function less ominous than it sounds) upon the dismantlement of SOE, where, according to Endnote 5, ‘his knowledge of the organisation proved “of untold value”’, and he joined the Foreign Office in 1948. He has a Personal File, HS 9/1653, at the National Archives.

Most security matters were quickly dispensed with at this meeting. Murphy then writes: “Three of the remaining points were felt to warrant legal advice. These concerned the notorious agent Henri Dericourt [sic] and the former second in command of the SOE’s French (F) Section, Nicholas [sic] Bodington.” A brief Endnote explains the facts of the case, but the legal ramifications of this rather startling observation, referring to an agent who was openly defined as ‘notorious’, and the outcome of the legal inquiry, are left mostly unresolved. Bodington was apparently allowed to read passages concerning himself, in the precincts of the French Embassy, but his reaction is unrecorded. Another request was made to the Office of the Treasury Solicitor, ‘with the request that certain passages be considered from a legal perspective, including references to the controversial [i.e. no longer ‘notorious’] agent Henri Dericourt’, but no outcome is recorded. Much of the last-minute negotiations were with Maurice Buckmaster, who had taken violent affront at the way he had been represented in SOE in France. Amazingly, he and Foot had never been allowed to meet during the compilation of the book. My interest was immediately piqued.

At some stage I hope to examine the relevant files, and shall arrange for them to be photographed. In the meantime, I am trying to determine what Foot wrote about Bodington and Déricourt in his original edition of SOE in France (1966), and the revision of 1968. Did he draw attention to Déricourt’s ‘notoriety’, and might it have been considered libellous? Déricourt had died in 1962 (apparently, although the facts are questionable), but Bodington lived on until 1974. The Wikipedia entry for Bodington makes references to Bodington’s later career in SOE, based on the 1966 text, that I cannot find in my 2004 edition, so I am keen to establish whether some degree of censorship was later applied. If any reader has any insights, please let me know. Meanwhile, I have ordered a copy of the 1966 edition, so that I may then follow Patrick Marnham’s precise references (since he also uses that edition), and then carry out a careful comparison of the texts. I shall report further at some stage.

Further Postscript

I somehow learned of a book on Déricourt by one Frank Rymills, also known as ‘Bunny’. I tracked down its editor, Bernard O’Connor, whom readers may remember as the author of a book on the Lena spies. He pointed me to the website where I could order it (it is a print-on-demand volume), and I did so. Rymills’s son, Simon, had retrieved his father’s memoir after listening to O’Connor deliver a talk at RAF Tempsford in 2012. It is a short volume, written by a pilot who was with 161 Squadron from January 1942 to July 1943, and took Déricourt as a passenger on several flights. What is more, he was a drinking-buddy of Déricourt’s in the Bedford area.

The book does not reveal many secrets, and relies much on Foot’s and Marshall’s work, supplemented by some lesser-known memoirs, but it offers one or two enticing items for me to follow up, such as the notion that Déricourt’s recall in April 1943 was a blind to mislead Boemelburg, and the highly intoxicating suggestion that the agents’ letters that he passed to the Gestapo may have been fakes, created as part of the general deception exercise. It also gave me another clue on the enigma of Foot’s versions of SOE in France. I shall report further anon. But it also led to one astonishing statement. I happened to find a review of the book on the Goodreads website, at https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/20738917-henri-dericourt-double-triple-or-quadruple-agent-frank-rymills , and I reproduce it here lest the text be suddenly expunged in President Xi Jinping style:

This is a very patchy account of this man Dericourt. He was recruited by the French Section of the Special Operations Executive by Maurice Buckmaster. It was a well known fact, and also Vera Atkins told me herself many years ago…she never trusted Dericourt, who was known to be in contact with German Officers he had known before the War.

Buckmaster, being the Head of The French Section of SOE…would have none of it, and continued to use Dericourt, to fly Agents and supplies into France in a Lysander airplane.

It became known later…when the Agents in France gave letters to be sent home via..Dericourt, he did hand these letters to German Intelligence Officers before returning them to England.

It is also known that Dericourt worked for…M15 British Intelligence and operated a mandate outside the workings of…SOE.

Dericourt was also the pilot who did bring to Britain in 1943…a very senior German Officer, who wanted to contact British Intelligence, he was part of a group of Officers who were going to overthrow..Adolf Hitler and arrange peace with the Allies.

These talks were held in secrecy with M15 Officers…and talks of the assassination of Adolf Hitler, and the forthcoming talks of Peace, with Germany left intact.

It is noted the bomb used in the Bomb Plot of July 1944, was in fact British made, which failed to kill Hitler.

This information on Henri Dericourt remains Classified until the year…2045.

Now the author of this piece, a Mr. Paul Monaghan, of Liverpool, H8, withdrew from Goodreads a month after this post, and is thus not accepting messages. His claim is spectacular, of course, and possibly contains just the correct amount of outrageousness to be worth investigating. It certainly smells of Dansey’s work, with Churchill even working behind the scenes. After the Rudolf Hess business, extreme discretion would be required not to upset Stalin about any negotiations, since the Marshall would suspect double-dealing behind his back. But who could the potential Hitler-overthrower be? One thinks first of Admiral Canaris, but he was head of the Abwehr, and Déricourt’s relationship with Boemelburg would not lead him to the despised Abwehr.