I recall, back in the early 1960s, seeing advertisements in the Daily Telegraph for a charity identifying itself as the Distressed Gentlefolk’s Aid Association. They showed an elderly couple, a rather tweedy gentleman of military bearing, and his elegant wife, who probably had worn pearls at some stage, but could no longer afford them. (The image I show above is a similar exhibit.) These were presumably persons of good ‘breeding’ who had fallen on undeserved hard times. The organization asked the readership to contribute to the maintenance and well-being of such persons.

I found these appeals rather quaint, even then, and asked myself why ‘gentlefolk’ should have been singled out as especially worthy of any handouts. After all, such terminology had a vaguely mid-Victorian ring: I must have been thinking of Turgenev’s ‘Nest of Gentry’, which I had recently read. Moreover, were there not more meritorious examples of the struggling poor? Perhaps I had Ralph MacTell’s ‘Streets of London’ ringing in my head [No. It was not released until 1969. Ed.], although I was never able to work out why, if the bag-lady celebrated by this noted troubadour (who, like me, grew up in Croydon in the 1950s) was lonely, ‘she’s no time for talking, she just keeps right on walking’. Was she perhaps fed up with being accosted in the street by long-haired minstrels wielding guitars?

But I digress. It was more probable that I had been influenced by the lunch monitor at my school dining-table, the much-loved and now much-missed John Knightly, who would later become Captain of the School. I recall how he, with Crusader badge pinned smartly on his lapel, would admonish those of us who struggled to complete our rather gristly stew by reminding us of ‘the starving millions in China’. I felt like telling him that he could take the remnants of the lunch of one particular Distressed Fourth-Former and send them off to Chairman Mao, but somehow the moment passed without my recommendation being made.

Astonishingly, I have discovered that the DGAA endured under that name until 1989, when it was renamed as Elizabeth Finn Care, after its founder. A fascinating article about it, before the name change, appeared in the New York Times that year: https://www.nytimes.com/1989/09/02/world/london-journal-lifting-a-pinkie-for-the-upper-crust.html?smid=em-share

I thought about that institution as I was preparing this piece. I have warned readers of coldspur that I would eventually be offering an analysis of the phenomenon of Liverpool University as the Home for Distressed Spies, and here it is. It analyses the predicament that MI5 and the civil authorities found themselves in when they had clear evidence that Soviet spies were in their midst, but, because of the nature of the evidence, believed that they could not prosecute without a confession.

The accounts of the interviews, interrogations and suspicions surrounding some of the atom scientists (Pontecorvo, Peierls, Fuchs, Skinner, Skyrme, Davison) in Britain after the war display a puzzled approach to policy by the officers at the AERE (Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell) and at MI5. If such suspects were believed to have pro-Soviet sympathies, they could not be encouraged, on account of the knowledge they possessed about atomic power and weaponry, to consider escaping to the Soviet Union. On the one hand, it would have been difficult to prosecute those whose guilt was hardly in doubt (i.e. Fuchs and Pontecorvo), as it would require gaining a confession from them, and, on the other, the sensitivity of the sources (the VENONA decrypts, and a lost item of intelligence, respectively) would prohibit such evidence being used in a trial. In Fuchs’s case, some senior figures in MI5 (Percy Sillitoe, the Director-General, and Dick White, head of counter-espionage) were keen on trying to gain a confession, and prosecuting. Liddell of MI5 (Sillitoe’s deputy), in conjunction with Harwell’s chief, John Cockcroft, and Henry Arnold, the security officer, wanted to shift Fuchs and Pontecorvo quietly off to a regional university. Liverpool University loomed largest in this scenario.

I have decided to work backwards generally in this account, before advancing to the connection between the controversial role of Herbert Skinner, and how he eventually exerted an influence on the removal of the mysterious Boris Davison. I believe it will be more revealing to display gradually the undeclared knowledge that affected the decisions, misleading briefings and reports that emanated from Guy Liddell and his brother-officers at MI5, and from other civil servants at Harwell, and at the Ministry of Supply, to which AERE reported.

The Dramatis Personae (primarily in 1950, when most of the action occurs):

At the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell:

Cockcroft Director

Arnold Security officer

Skinner Assistant director; Head of Theoretical Physics division

Fuchs Scientist

Pontecorvo Scientist

Davison Scientist

Buneman Scientist

Flowers Scientist

The Men from the Ministries:

Attlee Prime Minister

Portal Controller of Production, Atomic Energy, at the Ministry of Supply

Perrin Deputy to Portal

Appleton Permanent Secretary, Department for Scientific and Industrial Research

Makins Deputy Under-Secretary of State, Foreign Office

Bridges Permanent Secretary to the Treasury, and Head of Civil Service

Rowlands Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Supply

Cherwell Paymaster-General (1953)

At MI5:

Sillitoe Director

Liddell Assistant Director

White Head of B Division (counter-espionage)

Hollis B1

Mitchell B1E (Hollis’s deputy)

Robertson J. C. Head of B2

Robertson, T. A. R. B3 (retired in 1948)

Marriott B3

Serpell PA to Sillitoe

Skardon B2A

Reed B2A

Archer B2A

Collard C2A

Morton C2A

Hill Solicitor

Bligh Solicitor

At the Universities:

Mountford Vice-Chancellor, Liverpool University

Chadwick Master of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Oliphant Professor at Birmingham University

Peierls Professor at Birmingham University

Massey Professor at University College, London

Rotblat Professor at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London

Fröhlich Professor at Liverpool University

Frisch Professor at Trinity College, Cambridge

Flowers Researcher at Birmingham University

Pryce Professor at Clarendon Laboratories

The Journalists:

Pincher Daily Express

Stubbs-Walker Daily Mail

Moorehead Daily Express

Rodin Sunday Express

Maule Empire News

West New York Times

De Courcy Intelligence Digest

Various wives, mistresses, girl-friends and spear-carriers

Contents:

- Bruno Pontecorvo at Harwell

- Machinations at Liverpool

- Klaus Fuchs at Harwell

- Fuchs’s Interrogations

- Herbert Skinner at Harwell

- Skinner’s Removal?

- Skinner’s Ventures into Journalism

- Boris Davison – from Leningrad to Harwell

- Boris Davison – after Attlee

- Conclusions

- Bruno Pontecorvo at Harwell

Bruno Pontecorvo’s journey to Harwell was an unusual one. An Italian who worked with Joliot-Curie in Paris, he had escaped from France with his Swedish wife and their son in July 1940, in the nick of time before the Nazis overran the country. After some strenuous efforts visiting consulates and embassies to gain the necessary papers, he and his family gained a sea passage to the USA on the strength of a job offer from his Italian colleague Emilio Segrè in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

In the autumn of 1942, Pontecorvo was invited by Hans Halban to interview for a position with the British nuclear physics team working in Montreal. He was approved in December 1942, and was inducted into Tube Alloys, the British atomic weapons project, in New York, the following month. He was a success in Canada, and, after Halban’s demotion and subsequent return to Europe, worked closely with Nunn May on the Zero Energy Experimental Pile (ZEEP) project. Yet, as the war came to a close, Pontecorvo began to feel the anti-communist climate in Canada and the United States oppressive to him. In late 1945, with Igor Gouzenko and Elizabeth Bentley revealing the breadth and depth of the Soviet espionage network, he was happy to receive an informal job offer from John Cockcroft, who had been appointed head of the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell, which was to open on January 1, 1946. Chadwick, who had led the British mission to the Manhattan Project from Washington, had imposed travel restrictions on Pontecorvo, but the Italian was able to negotiate a satisfactory deal by the end of January 1946. Despite competitive offers from several prestigious US companies, he made his decision to join Harwell.

Yet, very strangely, Pontecorvo did not start work for three more years, continuing to operate in Montreal, and even travelling to Europe in the interim. In February 1948, he became a British citizen, to assuage government concerns about aliens working on sensitive projects. On January 24, 1949, he left Chalk River in Ontario for the last time, and officially started work at Harwell on February 1. An entry in his file at The National Archives, however, indicates that he was, rather late in the day, ‘nominated for a position at Harwell’, on July 7 of that year. Astonishingly, the record indicates that Pontecorvo was ‘confirmed in his appointment as S.P.S.O. [Senior Principal Scientific Officer] and established’ only on January 2, 1950! (KV 2/1888-2, s.n. 97c.)

It was not until October 1950, when Pontecorvo disappeared with his family during a holiday on the Continent, that Liddell made his first diary entry – at least, of those that have survived redactions – concerning Pontecorvo. As the record for October 21 states: “On information that had been received xxxxxxxxx in March of this year, intimating that PONTECORVO and his wife were avowed Communists, a decision was reached, after an interrogation of PONTECORVO by Henry Arnold, when the former admitted to having Communist relations – to get rid of him and find some employment for him at Liverpool University.” Yet Liddell thus implies that he (or MI5) learned of Pontecorvo’s unreliability only in March 1950, and his memorandum reinforces the notion that it was primarily the security officer Arnold’s idea to accommodate Pontecorvo at Liverpool University, even though the news had apparently come as a surprise to Arnold back in March.

Liddell was being deliberately deceptive. As early as December 15, 1949, (see KV 2/1288, s.n. 97A, as Frank Close reports in Half-Life, his biography of Pontecorvo), the FBI sent a report to MI5, dated December 15, that identified Pontecorvo’s links to Communism. As Close writes: ‘MI5 took note. Someone highlighted the above paragraph in Pontecorvo’s file’, but Close then asserts that MI5 did nothing, as they were consumed with the Fuchs case at the time. On February 10, 1950, however, another clearer warning arrived, when Robert Thornton of the US Atomic Energy Commission, on a visit to a Harwell conference, informed John Cockcroft that Pontecorvo and his family were Communists, repeating specifically the formal report from December. A vital conclusion must be that, if this visitor from the USA had not been invited to the conference, Cockcroft might never have learned about the project already in place to remove Pontecorvo.

Pontecorvo had in fact left behind him a trail of hints concerning his political allegiances. He had joined the French Communist Party on August 23, 1939, the day the Nazi-Soviet pact was signed. In July 1940, MI5 knew enough about him to judge him as ‘mildly unsuitable’ for acceptance as an escapee to Britain. In September, 1942, FBI agents had inspected his house in Tulsa (while Pontecorvo was away), and discovered communist literature there. After Pontecorvo’s application to join Tube Alloys, the FBI had exchanged correspondence with British Security Control (which represented MI5 and MI6 in the United States), concerning Pontecorvo’s loyalties. The FBI was able to confirm, after Pontecorvo’s flight, that it had sent letters to BSC on March 2, 16, and 19 but, inexplicably, BSC had issued him a security clearance on March 3, and had failed to follow up.

Alarmed by Thornton’s warning (having been kept in the dark by his own security officer and MI5), Cockcroft instructed Arnold to look into the matter. Arnold accordingly spoke to Pontecorvo, elicited information from him, and was able to inform MI5, by telephone call on March 1, that Pontecorvo was ‘an active communist’. (On the same day, Collard of C2A reported that Arnold’s conversation with Pontecorvo was ‘recent’: KV 2/1887, s.n. 20A.) Yet Arnold added more. He told MI5 that Pontecorvo had recently before been offered a job at the University of Liverpool, and that Pontecorvo’s acceptance of that offer would rid Harwell of a security risk. Again, this news goes unrecorded in Liddell’s diaries at the time.

But is this not extraordinary? What does ‘recently’ mean? If Arnold learned of the Liverpool job offer from Pontecorvo himself, when had it been arranged? And was this not extremely early for Pontecorvo to be seeking employment elsewhere? Given the long gestation period preceding the confirmation of Pontecorvo’s post at Harwell, would this not have provoked some high-level discussion? After all, Pontecorvo had been ‘established’ a couple of weeks after the original warning from the FBI. And who would have made the offer? Liverpool University is associated in the archives most closely with Herbert Skinner, but, as will be shown, Skinner was not yet established in a position of authority and influence at Liverpool. He had been formally appointed, but was not yet working full-time, as he was still executing his job as Cockcroft’s deputy at Harwell. Some senior academic figures should surely have been involved in the decision, especially the Vice-Chancellor, Sir James Mountford.

This aspect of the case has been strangely overlooked by Pontecorvo’s biographers, Frank Close, and Simone Turchetti. Both mention the fact that Pontecorvo had first indicated the fact of the Liverpool offer to Arnold on March 1, but do not follow up why it would have been made so early in the cycle, or investigate the earlier sequence of events, or even ask why Pontecorvo was informing Arnold of the fact. Had someone revealed to Pontecorvo that incriminating stories were floating around about his political beliefs, and had officers at Liverpool University come to some sort of unofficial agreement with the authorities at the Ministry of Supply and MI5 – but not Arnold or Cockcroft – since December? It is difficult to imagine an alternative scenario. Thus it is much more likely that MI5 did act in December, when they first received the report, but made no record of the fact.

Turchetti does in fact report that, in January 1950, i.e. well before the Arnold-Cockcroft exchanges, Herbert Skinner ‘asked Pontecorvo to join him at Liverpool, believing that he was the ideal candidate to lead experimental activities’, as if this would be a normal and smooth career progression. (I shall explore Skinner’s split role between Harwell and Liverpool later.) Turchetti does not, however, follow up on the implications of these early negotiations. For, as I suggested earlier, this would have been a very sudden transfer, given Pontecorvo’s official confirmation on the Harwell post earlier that month. Moreover, this item does not appear in the files at the National Archives. It comes from a statement made by the Vice-Chancellor at Liverpool, Sir James Mountford, which seriously undermines MI5’s claim that it was not aware of the seriousness of the exposure until February 1950. Pontecorvo, incidentally, also had the chutzpah around this time to request a promotion at Harwell, which was promptly rejected.

- Machinations at Liverpool

I acquired a copy of Mountford’s statement from Liverpool University. [By courtesy of the Liverpool University Library: 255/6/5/5/6 – Notes on Bruno Pontecorvo by James Mountford.]

It was sent by the Vice-Chancellor to Professor Tilley, in September 1978. Mountford explains that, after Sir James Chadwick in the spring of 1948 vacated the physics chair to accept the Mastership of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, the university was faced with the problem of finding a suitable candidate to replace him, with the added sensitivity that, if the right person were not selected, the nuclear project might be transferred to Glasgow. The challenge required some diligent networking by the experts in this field.

The first choice for Chadwick’s replacement was Sir Harrie Massey, the Australian Professor of Applied Mathematics at University College, London, who had had a distinguished war record, working lastly on isotope separation for the Manhattan Project at the University of California. (Mountford indicated that Massey was Professor of Physics, but he was in fact not appointed Quain Professor of Physics until 1950.) Massey ‘reluctantly’ declined the offer, so the team from Liverpool had a meeting on January 26, 1949, with Professor Oliphant of Birmingham (to whom Massey had reported at Berkeley), Chadwick, and Sir Edward Appleton, the Secretary of the Department for Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR). They decided upon W. H. B. Skinner of Harwell. Herbert Skinner headed the physics section there: he also had experience on the Manhattan Project, as he had worked with Massey on isotope separation at Berkeley.

There is, oddly, no discussion by the team of Skinner’s merits, nor even the suggestion of a process for interviewing Skinner, or asking him about his plans and objectives, or whether he even wanted the job. Cockcroft does not seem to have been consulted on his willingness to release his second-in-command so soon after the latter’s appointment. This must be considered as highly provocative and controversial, given Skinner’s role as Cockcroft’s deputy, and what Mountford wrote about the importance of the position, and I shall explore the rationale in detail later in this article. The note merely states: “He accepted and took up duties formally in Oct. 1949.” Moreover, Andrew Brown, in his biography of Joseph Rotblat, states that Rotblat had been appointed joint acting head of the physics department at Liverpool in October 1948, before resigning in March 1949. That happened to be just after the speedy decision in favour of Skinner, but Skinner does not even merit a mention in Brown’s book. * Did Rotblat perhaps think that his close friend Chadwick should have championed his cause instead of Skinner’s? Maybe he simply regarded the prospect of working under Skinner intolerable. Or perhaps he was asked to move aside to make room for a Harwell transferee?

[* Rotblat obtained a Ph.D., his second, from Liverpool in 1950. It seems that the Ph.D. was awarded after he moved to London.]

According to what Mountford claimed, Rotblat moved to St. Bartholomew’s Medical School not out of pique at Skinner’s appointment, but because of his dislike of military applications of nuclear science. Again, Mountford’s judgment (or memory) should be challenged. Rotblat had voiced his objections to the military uses of the science back in 1944, when it became apparent that the Germans would not be successful in building such a bomb. He had moved to Liverpool, which was constructing a cyclotron to aid applications for energy, was appointed Director of Research for Nuclear Physics at the university, and was Chairman of the Cyclotron Panel of the UK Nuclear Physics Committee from 1946 to 1950. He had thus had several years to have considered any objections to working there.

Irrespective of the exact circumstances concerning Rotblat’s departure, and whether he felt rebuffed, Skinner, on taking up his duties, raised the question of replacing Rotblat, and ‘the idea emerged’ of a second chair in Experimental Physics. Turchetti indicates, more boldly, that Skinner ‘dictated’ that the Faculty of Sciences agree to establish a professorship, as this would be the status that Pontecorvo demanded. Yet it is not clear where Turchetti gathered this insight, and it is not precisely dated. Mountford gives October 1949 as the time Skinner assumed his duties. Even if one considers it unlikely that a recruit not yet established would be able to make demands of that nature, if Skinner did indeed identify and recommend Pontecorvo that early, two months before the disclosures ofDecember 1949, it would have very serious implications, suggesting that MI5 and the Ministry already had reservations about the naturalised Italian. And, even in December 1949-January 1950, Skinner’s approaching Pontecorvo without informing his boss, Cockcroft, would have been highly irregular. Mountford may have been putting a positive gloss on the affair, but it now sounds as if undisclosed pressure was being applied from other quarters.

In any case (again, according to Mountford) the Faculty responded by agreeing, in principle, to approve the chair ‘if a satisfactory person were available’. The outcome was that Mountford lunched with Skinner and Pontecorvo on January 18, 1950, i.e. a month before the fateful visit of the American Thornton. Pontecorvo, according to Turchetti, was, however, not very impressed with Liverpool. (And his highly strung Swedish wife, Marianne, would have been very uncomfortable there: the wife of one of my on-line colleagues, a woman who hails from Sheffield, asserts that there was not much to choose between Moscow and Liverpool at that time.) Alan Moorehead wrote that Mrs. Pontecorvo visited the city, but was ‘worried about the cold in the north’ – so unlike her native Stockholm, one imagines. The Chairs Committee then spent three months or so collecting information about the candidate. Mountford had meanwhile spoken to Chadwick, who had doubts whether Pontecorvo could stand up to Skinner’s ‘forceful personality’. A formal interview with Pontecorvo eventually took place, but not until June 6, 1950. He did not overall impress, however, partly because of his poor English. Yet the committee overcame its reservations, and Pontecorvo would later accept the position, with January 1951 set as the date on which he would assume duties.

Mountford’s description of events as a smooth series is a travesty of what was really going on. Given what happened between January and June, Pontecorvo’s apparent freedom to accept or reject the offer in June was an unlikely outcome. First of all, in March, Pontecorvo had given Arnold the impression he had already received a firm offer, a claim belied by Mountford’s account. At this stage, Pontecorvo apparently did not respond to it, however vague and undocumented. Later that month, however, further damaging evidence against him came from Sweden via MI6 (a communication that was surely not passed on to Mountford). A letter from MI6 to the famous Sonia-watcher J.H. Marriott, in B2, dated March 2, 1950, describes Pontecorvo and his wife as ‘avowed Communists’. This revelation applied more pressure on MI5 and the Ministry of Supply to remove Pontecorvo from Harwell. The outcome was that, on April 6 (KV/2 -1887, s.n. 26) Arnold was again recommending that ‘it would be a good thing if he were able to obtain a post at one of the British universities’, even boosting the suggestion that ‘we might continue to avail ourselves of his undoubted ability as consultant in limited fields.’ The naivety displayed is amazing: Klaus Fuchs had just been sentenced to fourteen years for espionage activities.

Furthermore, Arnold added that Pontecorvo, after denying that he was a Communist, but admitting that he was assuredly a man of the Left, ‘has already toyed with the idea of an appointment in Rome University, and is at present turning over in his mind an offer which has come to him from America.’ The latter must have been an enormous bluff: given the FBI report, the United States would have been the last place to admit him for employment. This truth of his allegiance was soon confirmed, with matters became more embarrassing in July. Geoffrey Patterson in Washington then wrote to Sillitoe informing him that the FBI had learned of Pontecorvo’s working at Harwell, and had indicated that they had sent messages to Washington (and maybe London) on three occasions in 1943 describing Pontecorvo’s communist affiliations. The messages may have been destroyed, among the files of British Security Co-ordination, after the war. In Washington, as MI6’s representative, Kim Philby (of all people) could not trace them – or so he said. MI5 apparently had no record of them.

If the dons at Liverpool had been briefed on all that had happened, they presumably would have been even more reluctant to take Pontecorvo on. Yet, the more dangerous Pontecorvo seemed to be, the more MI5 wanted to plant him at Liverpool. Using FO 371/84837 and correspondence held in the Liverpool University Library, as well as the Pontecorvo papers at Churchill College, (none of which I have personally inspected), Turchetti writes: “From the spring of 1950, Skinner used his recent security investigations to put pressure on his colleague to accept the new position. He also convinced the university’s administrators of Pontecorvo’s suitability without making them aware of the ongoing inquiry.” In addition, with ammunition from Roger Makins from the Ministry of Supply, Skinner had to wear down objections from university administrators that Pontecorvo was improperly qualified to teach. Skinner was clearly receiving instructions from his political masters.

Chadwick and Cockcroft acted as referees for Pontecorvo, but they could hardly be assessed as objective, given their involvement in the plot. Chadwick pondered over whether he should confide in Mountford with the awful facts, and wrote to him that he would discuss the university’s concerns with Cockcroft, but he did not follow up. And then, when the final offer was reluctantly made on June 6, Pontecorvo vacillated, requesting another month to consider. On July 24, the day before he left on holiday, never to return, he wrote to Mountford, accepting the offer, and stating that he expected to start work after Christmas, when he would leave Harwell.

On October 23, 1950, Liddell had an interview with Prime Minister Attlee. He glossed over the FBI/BSC issue without giving it a date, and referred solely to the Swedish source of March 2 as evidence of Pontecorvo’s communism, conveniently overlooking both the events of December 1949 and February 1950. All this is confirmed by his memorandum of the meeting on file (KV 2/1887, s.n. 63A). MI5 had been attempting a reconstruction of Pontecorvo’s activities (KV 2/1288, s.n. 87C), which presumably fed Liddell’s intelligence. This account (undated, but probably in July or August 1950) omits both the warning from the FBI in December 1949 (which is confirmed elsewhere in the file), as well as the information given to Cockcroft at the beginning of March 1950. It does concentrate, however, on the information from Sweden, reporting on the discussions that occurred in the following terms: “D. At. En. [Perrin, at Department of Atomic Energy] decided not to grant PONTECORVO’s request for promotion and to encourage him to take up the post offered him at Liverpool by Professor Skinner. This was arranged only after considerable discussion.” Pontecorvo was thus allowed to leave on vacation in July without submitting his resignation or formally being taken off Harwell’s books. And he never returned.

Yet his whole saga eerily echoes what had happened in a collapsed time-frame with Klaus Fuchs.

- Klaus Fuchs at Harwell

Fuchs’s path to Harwell was slightly less erratic, but also controversial. He had been recruited to Tube Alloys, the British codename for atomic weapons research, in 1941, and had moved to the USA at the end of 1943 to work on the Manhattan Project. In June 1946 he was summoned from Los Alamos to head the Theoretical Physics Division at Harwell, working under Herbert Skinner. Skinner had been the first divisional head appointed at Harwell. Fuchs was appointed chairman of the Power Steering Committee at Harwell, and Pontecorvo joined the committee later.

What is extraordinary about Fuchs’s return to the UK is that the first that MI5 learned about it was when Arnold, the security officer, wrote to MI5, in October 1946, about his suspicions that Fuchs might be a communist. He might well have gained his intelligence from Skinner himself, who had known Fuchs from the time they both worked at Bristol University in the 1930s. The political climate by this stage meant that embryonic ‘purge’ procedures (which were solidified in May 1947) would have to be applied to such figures working in sensitive posts. Frank Close, in Trinity, covers very thoroughly these remarkable few months at the end of 1946, when MI5 officers openly voiced their concerns that Fuchs might be a spy. Michael Serpell and Joe Archer (Jane Archer’s husband) were most energetic in advising that Fuchs should be kept away from any work on atomic energy or weapons research. Rudolf Peierls came under suspicion, too, but Roger Hollis countered with a strong statement that it was highly unlikely that the two were engaged in espionage, and gained support in his judgment from Dick White and Graham Mitchell.

The next three years were thus a very nervous time for MI5 and Arnold, as they kept a watch on Fuchs’s movements and associations. Yet Fuchs was placed on ‘permanent establishment’ in August 1948, and Arnold was later to claim, deceitfully, that Fuchs came under suspicion only in that year, when he was observed speaking intently to a known communist at a conference. The matter came to a head, however, in 1949, when the decipherment of VENONA transcripts led the Washington analysts to narrow down the identity of the spy CHARLES to either Fuchs or Peierls. Guy Liddell indicates that fact as early as August 9: at the end of August, the FBI formally told MI5 of its belief that the leak pointed to Fuchs (because of the visit to his sister in Boston).

MI5 immediately started making connections. It alerted MI6 to the Fuchs case, and to his Communist brother, Gerhard. (Maurice Oldfield had told Kim Philby of the discovery before the latter left London for Washington in September 1949.) MI5 identified the close relationship between the Skinners and Fuchs. A report by J. C. Robertson (B2A) of September 9 (after a meeting between Arnold, Collard, Skardon and Robertson) runs as follows: “Although FUCHS’ address has until recently been Lacies Court, Abingdon, he has in fact rarely lived there, but has chosen to sleep more often than not with his close friends the SKINNERS at Harwell. He is on more than usually intimate terms with Mrs. SKINNER. The SKINNERS will be leaving in about six months for Liverpool, where SKINNER himself is to take up the chair about to be vacated [sic!] by Sir James Chadwick. At present, SKINNER devotes his time about half and half to Liverpool and Harwell.”

Robertson went on to write that Professor Peierls was also a regular visitor at the Skinners, and that Fuchs was in addition very friendly with Otto Frisch of Cambridge University. (Frisch, the co-author, with Rudolf Peierls, of the famous memorandum that showed the feasibility of building a nuclear weapon, had moved to Liverpool from Birmingham, where Peierls worked, and had been responsible for the development of the cyclotron developed there. Yet, after the war, he had taken up work at Harwell as head of the Nuclear Physics Division, before moving to Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1947.) At Harwell, Arnold alone was in on the investigation: Cockcroft was not to be told yet of what was going on.

This is an intriguing document, by virtue of what it hints at, and what it gets wrong. The suggestion that Fuchs is having an affair with Erna Skinner is very strong, and the mention of Herbert’s long absences in Liverpool indicates the opportunities for Fuchs and Erna to carry on their liaison. Yet the transition of the Liverpool chair remains confusing: Chadwick had moved to Cambridge in 1948; Mountford noted that Skinner had taken up his duties in October 1949, but also referred (well in retrospect) that there had been an interregnum in the Physics position for a year, from March 1948 to March 1949. Robertson indicates that the Skinners will not be moving until about March 1950. Skinner’s own file at the National Archives informs us that he did not resign from Harwell until April 14, 1950, which was a very late decision, suggesting perhaps that his preferences had lain with staying at Harwell as long as possible, and that he might even have had aspirations of restoring his career there. The files suggest that his duties at Harwell remained substantial well into 1950. A report by J. C. Robertson of B2A, dated March 9, 1950, describes Skinner as follows: ’. . . deputy to Sir John Cockcroft and who has temporarily taken over Fuchs’ post as head of the Theoretical Physics Division at Harwell’. Skinner then continued to work in a consultative capacity at Harwell: he wrote to the incarcerated Fuchs as late as December 20, 1950 that ‘we are definitely at Liverpool but go on visits to Harwell quite often.’ How could Skinner perform that job if he was spending so much his time in Liverpool? In any case, it was an exceedingly long and drawn-out period of dual responsibilities for Skinner.

- Fuchs’s Interrogations

Armed with their confidential VENONA intelligence, MI5 prepared for the interrogation of Fuchs, but were not initially hopeful of gaining a successful confession. Thus the thorny question of what they could collectively do to ‘eliminate’ him (in their clumsy expression) quickly arose. Fuchs might decide to flee the country, which would be disastrous, as his Moscow bosses would be able to pick his brains without any restrictions. Liddell continued the theme, showing his enthusiasm for a softer approach against his boss’s more prosecutorial instincts. Liddell doubted that interrogations would be successful in eliciting a confession from Fuchs, and, as early as October 31, 1949, he was suggesting ‘alternative employment’, though being overruled by Sillitoe. At this stage, Peierls and Fuchs were both under investigation, but Liddell was gaining confidence that Fuchs was ‘their man’. (Peierls had come under suspicion in August since he also had a sister in the United States, but he was soon eliminated from the inquiry.)

On November 28, Liddell noted that he was still thinking in terms of finding another job for Fuchs, and on December 5, he tried to convince Perrin that the chances of a conviction were remote, saying that ‘efforts should be made to explore the ground for alternative work’. At a meeting to discuss Fuchs on December 15, 1949 (see Close, p 255), Perrin ‘commented that Herbert Skinner was about to move to Liverpool University, and that a transfer of Fuchs to Liverpool might be arranged through Skinner, who would probably welcome Fuchs’ presence there.’ (Perrin was presumably unaware then of the Erna Skinner-Klaus Fuchs liaison.) It seems that the notion of parking Fuchs specifically at Liverpool University was first aired at this time. (Note that this is exactly the same date when MI5 learned about Pontecorvo from the FBI.) When Jim Skardon managed to get Fuchs to make a partial confession on December 21, Liddell was still considering finding him ‘some job at some University compatible with his qualifications’.

After another interrogation of Fuchs, on December 30, Liddell met the Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, on January 2, 1950, and informed him of MI5’s resolve to complete the interrogations. Even Lord Portal (head of Atomic Energy at the Ministry of Supply) was in general harmony, although reportedly bearing the more cautious opinion that ‘the security risk of maintaining FUCHS at Harwell could not be accepted, and that some post should be found for him at one of the Universities’. Attlee seemed ready to accept Portal’s recommendation. Yet two important players had yet to be brough into the plot: Cockcroft and Skinner.

When Cockcroft became involved, matters took an alarmingly different turn. Cockcroft asked Skinner, on January 4, whether he could find a place for Fuchs at Liverpool. This would suggest that, unless a deep feint was being played, Skinner was not aware of the clandestine efforts to dispose of Fuchs, as his depositions to Liverpool had hitherto been made with Pontecorvo in mind. Skinner must surely have been bemused, and must have asked why such a step was being considered. Cockcroft probably said more than he should have. (Cockcroft had the irritating habit of concealing his opinions in meetings with his subordinates, and then showing disappointment when his intentions were not read, but then talking too much in one-on-one conversations.) On January 10, Cockcroft met with Fuchs and Skinner, separately. Cockcroft told Fuchs ‘that he would help him find a university post and suggested that Professor Skinner might be able to take Fuchs on at Liverpool’. It also reinforces the fact that Cockcroft had not been brought into the Pontecorvo affair. Astonishingly, all the time up until March 1, Skinner was negotiating with Pontecorvo and Mountford behind Cockcroft’s back, while Cockcroft was pressing Skinner (up until Fuchs’s confession on January 24) to place Fuchs at Liverpool without bringing Skinner into the full picture.

Whether Skinner learned about Cockcroft’s offer to Fuchs from Cockcroft or Erna is not clear, but MI5 reported that Skinner learned ‘considerably more about the Fuchs affair than he is authorized to know’, and (as Close writes), ‘in consequence decided to take steps to ensure that Fuchs stayed at Harwell’. Given the circumstances, this was not surprising. Skinner already had been promoting Pontecorvo’s case, and because of Erna, would surely have preferred that Fuchs stayed at Harwell. So much for Skinner as the enabler of graceful retirement, but he had been placed in an impossible position. He had been thrust into the middle of these negotiations, perhaps reluctantly. In the course of one month (January 1950), Cockcroft applied pressure on him to accept Fuchs at Liverpool, Skinner next privately tried to talk Fuchs out of the move, and then, even before Fuchs made his confession, Skinner met with Mountford and Pontecorvo to consider a position for Pontecorvo at the University. It did not appear that his bosses at Harwell and the Ministry of Supply were behaving very sensitively to his own needs. At the same time, they were very anxious to make sure that Skinner kept to himself anything he may have learned about the predicament that Fuchs – and the authorities – were in.

Here also occurred the highly questionable incident of ‘inducement’, highlighted by Nancy Thorndike Greenspan in her recent biography of Fuchs, whereby Cockcroft essentially offered Fuchs a free pass if he co-operated, stressing that the recent appointment of Fuchs’s father to a position in East Germany made Klaus’s employment at Harwell untenable. Cockcroft also famously suggested that Adelaide University might be an alternative home, a suggestion which left Dick White and Percy Sillitoe aghast. Adelaide University happened to be the alma mater of Mark Oliphant, who had been a colleague of Peierls at Birmingham, and had also worked on isotope separation at Berkeley. (These connections go deep.) Oliphant’s biographical record suggests that he returned to Australia after the war, yet he is recorded by Mountford as attending the fateful meeting in January 1949 to decide on Skinner as Chadwick’s successor. No ground appeared to have been prepared for this idea, and the incident, while suggesting Cockcroft’s political naivety, also hints that Oliphant had been brought into the discussions some time before. MI5 struggled with the challenge of trying to coordinate the roles of Arnold, Skinner and Cockcroft, all with different needs, perspectives, and all being granted only a partial side of the story.

On January 11, Liverpool University decided to recommend the establishment of a second chair in Physics: perhaps Mountford was not yet aware that he was about to face two candidates for one position. On January 18, Skinner brought Pontecorvo up for a meeting with Mountford. Then some of the pressure was relieved. On January 24, Fuchs made a full confession to Jim Skardon, in the fourth interrogation. He was arrested on February 2, sent to trial, and sentenced to fourteen years’ imprisonment on March 1. For a while, Liverpool University was saved the embarrassment of being forced to accept one dangerous communist spy in its faculty. What Adelaide University thought about all this (if they were indeed consulted) is probably unrecorded.

- Herbert Skinner at Harwell

I wrote about Skinner’s enigmatic career in the second installment of The Mysterious Affair at Peierls. He had enjoyed a distinguished war record, both in Britain in the USA, and merited his appointment as Cockcroft’s deputy at Harwell, where he was apparently a very hard and productive worker. Yet he had some facets to his character and lifestyle that raised security questions – not least the fact that he had married Erna, an Austrian born in Czernowitz, who socialized with openly communist friends. (The unconventional lives and habits of the Skinners assuredly deserve some special study of their own.) Despite their background, it appears (unless some files have been withheld) that MI5 began keeping record on the pair only towards the end of 1949, even though Erna had for a while maintained frequent social contact with her Red friends, including Tatiana Malleson. The statements that Skinner made, when later questioned by MI5, that protested innocence, could be interpreted as the honest claims of a loyal civil servant, or the obvious cover of a collaborator in subversion. (That is the Moura Budberg ploy with H. G. Wells, who, when asked by ‘Aitchgee’ whether she was a spy, told him that, whether she were a spy or not, she would have to answer ‘No.’)

Moreover, Erna was carrying on an affair with Fuchs, taking advantage of Herbert’s frequent absences when he was splitting his time between Liverpool and Harwell, but also acting brazenly when her husband was around. In the last months of 1949, the Erna-Klaus relationship was allowed to thrive. As Close writes (Trinity, p 244): “Because Erna’s husband, Herbert, was in the process of transferring from Harwell to take up a professorship at the University of Liverpool, he was frequently away from the laboratory, so there were many empty hours for Erna, which she would pass with Fuchs.” If they were not aware of it before, MI5 could not avoid the evidence when they started applying phone-taps to Fuchs’s and the Skinners’ telephones. Skinner was thus a security risk himself.

Skinner, who had known Fuchs since their Bristol days, also made some bizarre and contradictory statements about Fuchs’s allegiances, at one time, in 1952, admitting that he had known that Fuchs was an ardent communist when at Bristol, but did not think it significant ‘when he found Fuchs at Harwell’, having earlier criticised MI5 for allowing Fuchs to be recruited at the Department of Atomic Energy. On June 28, 1950, when Skardon interviewed Skinner about Fuchs, the ex-Special Branch officer reported his response as following: “Dr. Skinner was somewhat critical of M.I.5 for having allowed Fuchs, a known Communist, to be employed on the development of Atomic Energy, saying that when they first met the man at Bristol in the 1930’s he was clearly a Communist and a particularly arrogant young pup. He was very surprised to find Fuchs at Harwell when he arrived there to take up his post in 1946. Of course I asked Skinner whether he had done anything about this, pointing out that we were not psychic and relied upon the loyalty and integrity of senior officers to disclose their objections to the employment of junior members of the staff. He accepted this rebuff.”

Yes, that response was perhaps a bit too pat, rather like Philby’s memoranda to London from Washington, where he brought attention to Burgess’s spying paraphernalia, and later to Maclean’s possible identity as the Foreign Office spy, as a ploy to distract attention from himself. Fuchs ‘clearly a Communist’ – that should perhaps have provoked a stronger reaction, especially with Skinner’s assumed patriotism. But his claim was certainly fallacious: Skinner’s Royal Society biography makes it clear that he was busy supervising construction at Harwell in the first half of 1946, substituting for Cockcroft, who did not arrive until June. Fuchs did not arrive until August, and Skinner must have known about his coming arrival, and even facilitated it.

In addition, early in 1951, after Skinner had moved full-time to Liverpool, Director-General Sillitoe wrote to the Chief Constable of Liverpool, asking him to keep an eye on the Skinners. A Liverpool Police Report was sent to MI5 on May 10, indicating that the Skinners had been active members of the local Communist Party ‘since they arrived in Liverpool from Harwell almost two years ago’. (The timing is awry.) Faulty record-keeping? The wrong targets? A mean-spirited slur by a rival who resented Skinner’s appointment? A reliable report on some foolish behaviour by the new Professor? Another mystery, but a pattern of duplicity and subterfuge on his part.

Skinner’s actions are frequently hard to explain. In my recent bulletin on Peierls, I reported at length on the mysterious meetings that Skinner held with Fuchs in New York in 1947, when they were attending the Disarmament Conference. This episode was described at length by the FBI, but appears to have been overlooked (if available) by all five of Fuchs’s biographers: Moss (1987), Williams (1987), Rossiter (2014), Close (2019), and Greenspan (2020). More mysteriously, Skinner’s conversations with Fuchs suggested that he had a confidential contact at MI6. Was Skinner perhaps working under cover, gathering information on Communists’ activities?

Thus it is not surprising that Skinner might not have embraced the prospect of Fuchs’s joining him (and Erna) at Liverpool once his assignments at Harwell had been cleared up. Could he not get that ‘young pup’ out of his life and his marriage? The record clearly shows that, after Skinner had been instructed by Cockcroft to show no curiosity in what was going on with the Fuchs investigation, Fuchs admitted his espionage to Erna on January 17, after which she told her husband. By January 27, Robertson is pointing out that Skinner has been told too much by Cockcroft (who was not good at handling conflict), and that Skinner has been trying to persuade Fuchs to stay at Harwell. This particular crisis was held off by the fact that Fuchs had, shortly beforehand, made his full confession to Skardon, and the strategy favoured by White and Sillitoe of proceeding to trial began to take firm shape.

The files on the Skinners at the National Archives (KV 2/2080, 2081 & 2082) reveal yet more twists, however, indicating that there were questions about Skinner much earlier, and also showing a remarkable exchange a couple of years after the Pontecorvo and Fuchs incidents, when Skinner naively exposed, to an American publication, the hollowness of the government’s policy.

- Skinner’s Removal?

We have to face the possibility that Skinner’s move away from Harwell had been planned a long time before. One remarkable minute from J. C. Robertson (B2A), dated July 20, 1950, is written in response to concerns expressed from various quarters about the Skinners’ Communist friends, and includes the following statement: “We agreed that since the SKINNER’s [sic], on their own admission, have Communist friends, they may share these friends [sic] views, and that Professor SKINNER’s removal from Harwell to Liverpool University should not therefore be a ground for the Security Service ceasing to pay them attention.” ‘Removal’ is a highly pejorative term for the process of Skinner’s being appointed to replace the highly-regarded Chadwick. Was this a misunderstanding on Robertson’s part as to why Skinner was leaving? Was it simply a careless choice of words? Or did it truly reflect that the authorities had decided that Skinner was a liability two years before?

The suggestion that Skinner was ‘removed’ might cause us to reflect on the possibility that Chadwick was encouraged to take up the appointment at Cambridge in order to make room for Skinner. What is the evidence? Chadwick was assuredly an honourable and effective leader of the Tube Alloys contingent in the USA and Canada. He forged an effective partnership with the formidable General Leslie Groves, who led the Manhattan Project, but who was very wary of foreign participation in the exercise. Yet Chadwick became stressed with his role, conscience-strung by the enormity of what was being created, and not always being tough enough with potential traitors.

Chadwick had made some political slip-ups on the way. He had been criticised by Mark Oliphant for not being energetic enough in the USA, he had provided a reference for Alan Nunn May for a position at King’s College London just before Nunn May was arrested, and, in a statement that perturbed many, he would later openly express his approval of Nunn May’s motives, while saying he did not support what his friend did. He had also given support to the questionable Rotblat when the latter announced his bizarre plan to parachute into Poland. He had appointed another scientist with a questionable background, Herbert Fröhlich, just before his departure from Liverpool. Moreover, while he had openly supported Cockcroft’s appointment, he was not overall happy with the separation of R & D from production of nuclear energy. He and Cockcroft were both building cyclotrons, and thus rivals, but Cockcroft was gaining more funding. Rotblat told Chadwick that Harwell was offering larger salaries. The feud over budgets simmered in the two short years (1946-1948) while Chadwick was at Liverpool.

He was reluctant to leave Liverpool, Mountford reported, even though he was admittedly an exhausted figure by then. His staff did not want him to leave, either, and he maintained excellent relations with Mountford himself. By 1948, Perrin – who reported to the strict and disciplined Lord Portal at the Ministry of Supply – and MI5 were following through Prime Minster Attlee’s instructions to tighten up on communist infiltration, as the Soviet Union’s intentions in Eastern Europe became more threatening. Thus installing Cockcroft’s number two at Liverpool would have allowed the removal of a competent leader who had made an embarrassing choice of wife, place an ally of Cockcroft’s at the rival institution, and set up a function that could assimilate unwanted leftists from Harwell. Overall, Cockcroft trusted Skinner, who had worked for him very effectively on radar testing in the Orkneys at the beginning of the war, but he had to be made to understand that Skinner’s wife’s friends were a problem.

Thus, if Chadwick was pushed out to make room for Skinner, what finally prompted the authorities to eject him? It looks as if Liddell, White and Perrin were pulling the strings, not Cockcroft. Arnold, the security officer, stated in October 1951 that Fuchs’s close relationship with Erna Skinner had started at the end of 1947. November 1947 was the month that the three of them were in New York. The injurious FBI report may have been sent to MI5, but subsequently buried. Thus MI5 officers, already concerned about Fuchs’s reliability, might in early 1948 have seen Skinner as a liability as well, arranged the deal with Perrin and Oliphant, convinced Chadwick (who had, of course, moved on by then) of Skinner’s superior claim over Rotblat and Fröhlich, and set the slow train in motion. It was probably never explained to Cockcroft what exactly what was going on.

It is possible that MI5 had seen the problem of disposing of possible Soviet agents coming some time before. Chapman Pincher had announced, in the Daily Express in March 1948, that the British counter-espionage service had been investigating three communist scientists at Harwell. This triad did not include Fuchs or Pontecorvo, however, since two months later Pincher reported that all three had been fired. In a memo written in August 1953, when Skinner was in some trouble over a magazine article [see next section], R. H. Morton of C2A in MI5, having sought advice from one of MI5’s solicitors, ‘S.L.B.’ (actually B. A. Hill of Lincoln’s Inn), stated that ‘The Ministry of Supply should be asked whether Skinner was ever in a position to know during the Fuchs investigation that although we knew Fuchs was a spy, he was allowed to continue at Harwell for a time’.

This is an irritatingly vague declaration, since ‘for a time’ could mean ‘for a few weeks’ or ‘for a few years’, or anything in between. Yet it specifically states ‘was a spy’, not ‘was under suspicion because he was a communist’. According to the released archives, that recognition did not occur until September 1949. If the solicitor and the officer were aware of the rules of the game, and the impossibility of immediate removal or prosecution, they might have been carelessly hinting at earlier undisclosed events, and that the Ministry of Supply had initiated stables-cleaning moves that took an inordinate amount of time to complete.

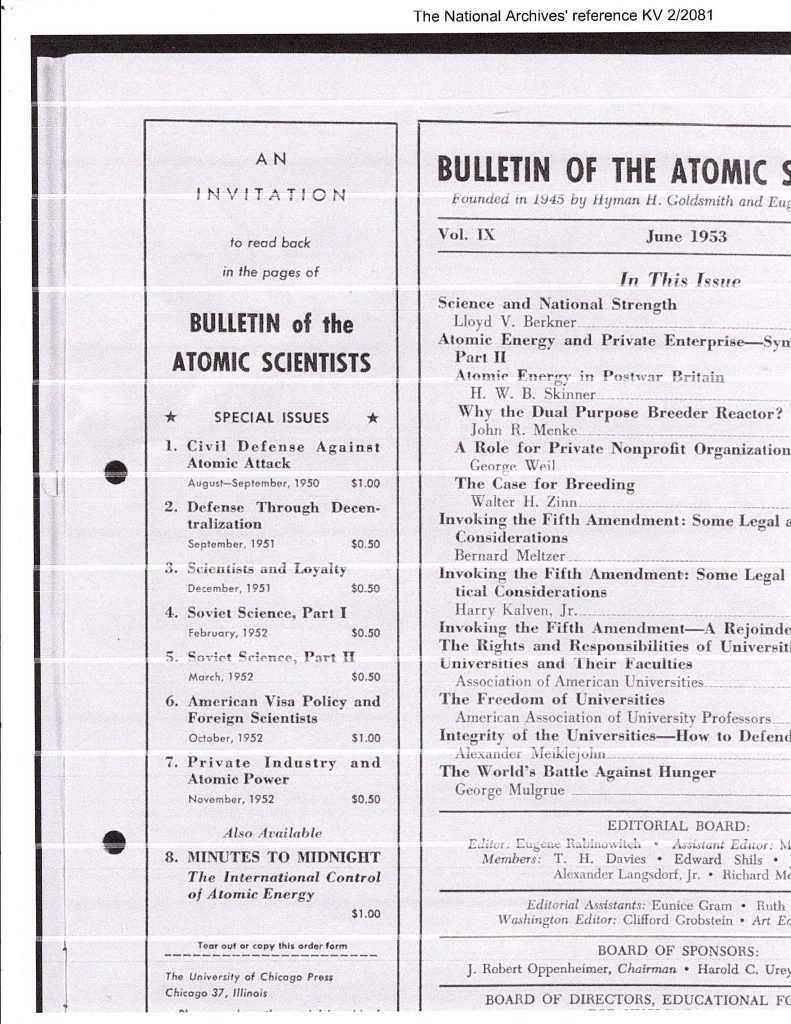

- Skinner’s Ventures into Journalism

Herbert Skinner later drew a lot of unwelcome attention to himself in two articles that he wrote for publication. In August 1952, John Cockcroft invited him to review Alan Moorehead’s book, The Traitors (a volume issued as a public relations exercise by MI5) for a periodical identified as Atomic Scientists’ News (in fact, more probably the American Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists). And in June 1953, Skinner published an article in the same Bulletin, titled ‘Atomic Energy in Post-War Britain’. In both pieces he betrayed knowledge that was embarrassing to MI5.

He was sagacious enough to send a draft of his book review to Henry Arnold on September 18, 1952, in particular seeking confirmation of the fact that Fuchs’s confession to Skardon occurred in two stages, and to verify his impression that the information that came from Sweden in March of 1950 applied only to Mrs. Pontecorvo. He wrote: “But I know K confessed to Erna about the Diff. Plant a day or two prior to Jan. 19th (the date when he was considered for the Royal Society. This is confidential but did you know it?)” Skinner felt that Moorehead’s account had been telescoped, and wanted to correct it. As for the communication from Sweden, Skinner based his recollection on what Cockcroft had told him, expressing the opinion that, since Pontecorvo had spent so little time in Stockholm, it was unlikely that data had been gathered about him.

The initial response from MI5 was remarkably light. Skardon (B2A) cast doubt on the earlier January 17 confession, and suggested that the claim should be followed up with Mrs. Skinner. His boss, J. C. Robertson, was however a bit more demanding, requesting, in a reply to Arnold dated September 24, that an entire paragraph, about Fuchs’s confessions, and the pointers to a leakage arriving from the USA, be removed. [The complete text of the draft review is available in KV 2/2080.] He added: “I understand that you will yourself be pointing out to SKINNER the undesirability of making any reference to the report from Stockholm which he quotes at the bottom of Page 9 of his manuscript.”

This latter observation was a bit rich and ingenuous. All that Skinner did was attempt to clarify a statement made by Moorehead about the Swedish report, and Moorehead had obviously been fed that information by MI5. Moorehead’s text (pp 184-185) runs as follows: “Indeed Pontecorvo was not persona grata any longer, for early in March a report upon him had arrived from Sweden and this report made it clear that not only Pontecorvo but Marianne as well was a Communist.” Moorehead went on to write that ‘there was nothing to support this in England or Canada [or the USA?], but it was evident that he would have to be closely watched’. Here was an implicit admission that MI5 had blown its cover by allowing Moorehead to see this information. MI5 wanted to bury all the intelligence about Pontecorvo that had come in from the USA, and Robertson clearly wanted to distract attention away from Sweden, too. The Ministry of Supply also issued a sharp admonition that the item about Sweden in Moorehead’s book should never have passed censorship. One wonders what Clement Attlee thought about this anomaly.

The outcome was that Skinner had to make a weird admission of error. First of all, he agreed that he found Moorehead’s mentioning of the Swedish reference ‘unfortunate’, but insisted that he was not in error over Erna’s distress call to him on the 17th, after Fuchs had confessed to her. This prompted Arnold to raise his game, and try to talk Skinner out of submitting the review entirely, as he was using personal information from his role at Harwell, and it would raise ‘a hornet’s nest’ of publicity. He even suggested to Skinner, after lunching with him and Erna, that his memory of dates must be at fault. Even though no statement to that effect is on file, Robertson noted on October 30 that Skinner ‘has now admitted that he may have been mistaken’. (But recall Robertson’s statement of January 27, described above, which indicated that Skinner had already tried to convince Fuchs to stay at Harwell.) Robertson added that ‘we have never been very happy about Mrs. SKINNER, who was of course FUCHS’ mistress’, but announced that MI5 no longer need to interview her about the matter. Robertson alluded to the fact that MI5’s own records pointed to the absence of any evidence of any ‘confession’ by Fuchs to Mrs. Skinner, but how such an event would even have been known about, let alone recorded, was not explained.

It appears that, after this kerfuffle, the review was not in fact published, but Cockcroft and Skinner did not learn any lessons from the exercise. In the June 1953 issue of the Bulletin appeared a piece titled ‘Atomic Energy in Postwar Britain’. The article started, rather dangerously, with the words: “I think that I, who was a Deputy Director at Harwell from 1946 to 1950, am by now sufficiently detached to write my own ideas without these being confused with the British official point of view.” Skinner went on to lament the decline in cooperation between the USA and Great Britain, although he openly attributed part of the blame to the Nunn May and Fuchs cases. But he then made an extraordinarily ingenuous and provocative statement: “It is true that we have had on our hands more than our fair share of dangerous agents who have been caught (or who are known).”

What could he have been thinking? Sure enough, the Daily Mail Science Correspondent J. Stubbs Walker picked up Skinner’s sentence in a short piece describing how Britain was attempting to convince Washington that its security measures were at least as good as America’s. Equally predictably, the MI5 solicitor B. A. Hill was rapidly introduced to the case, and, naturally, drew the conclusion that Skinner’s words implied that there were other agents known, but not yet prosecuted, at Harwell. He thus asked Arnold, in a meeting with Squadron Leader Morton (C2A), whether Skinner had read Kenneth de Courcy’s Intelligence Digest, since de Courcy (a notorious rabble-rouser who was a constant thorn in MI5’s flesh) had made a similar statement in the Digest of the preceding March that ‘there were still two professors employed at Harwell who were sending Top Secret information to the Soviet Union’.

Fortunately for his cause, Skinner had written to the Daily Mail to explain what he wrote, and how it should have been interpreted. (He assumed that Stubbs Walker must have picked up his statement from the UK publication, the Atomic Scientists’ News, which published the same text in July, but, while the archive contains all the pages of the issue of the American periodical, it does not otherwise refer to the UK publication.) “The parenthesis was simply put in to cover the case of Pontecorvo,” he wrote, “and I would like to make it clear that I have no knowledge whatever of any other agents not convicted.” It was a clumsy attempt at exculpation: the syntax of the phase ‘who are known’ clearly indicates a plurality.

Yet what was more extraordinary is that, again, Skinner had written the article at the request of the hapless Cockcroft, ‘who read the article before it was despatched’. Moreover, a copy also was sent to Lord Cherwell’s office, and an acknowledgment indicated that ‘Lord Cherwell had read the majority of the article’. Perhaps Lord Cherwell, Churchill’s wartime scientific adviser, and in 1953 Paymaster-General, now responsible for atomic matters, should have read the article from beginning to end. Perhaps he read all he was given, because Skinner was able to produce a letter from Cherwell at the end of August, indicating that he had no comments. Yet what was sent to Cherwell was a ‘draft of the first half of the paper’. The offending phrase did indeed appear near the beginning of the article: Skinner was given a slap on the wrists, and sent away. Whether Cockcroft was rebuked is unknown. A revealing note in Skinner’s file, dated June 12, 1953, reports that Cockcroft would probably be leaving Harwell soon, to replace Sir Lawrence Bragg as head of the Clarendon Laboratory. Morton notes: “Rumours indicate Skinner in the running to replace him. Arnold considers this most undesirable ‘for obvious reasons’.” But it is an indication that Skinner still regarded his sojourn at Liverpool as temporary, and wanted to return to replace Cockcroft.

The MI5 solicitor made an unusual error of judgment himself, however. In that initial memorandum of August 12, when he had evidently discussed the matter with some MI5 officers, he included the following: “On the other hand it was not generally thought [note the bureaucratic passive voice] that when he wrote the article he was in fact quoting DE COURCY, but rather that he had in mind cases such as Boris DAVIDSON, and what he really meant to say was that there were persons at Harwell who were suspected of being enemy agents but had not yet been prosecuted, though they were suspected of acting as enemy agents.” That was an unlawyerly and clumsy construction – and it should have been DAVISON, not DAVIDSON – but the implication is undeniable. ‘Cases such as Boris DAVIDSON’ clearly indicates a nest of infiltrators. And I shall complete this analysis with a study of the Davison case.

- Boris Davison – from Leningrad to Harwell

The files on Boris Davison at the National Archives comprise nine chunky folders (KV 2/2579-1, -2 and -3, and KV 2/2580 to KV 2/2585), stretching from 1943 to 1954. They constitute an extraordinary untapped historical asset, and merit an article on their own. (Equally astonishing is that Christopher Andrew’s authorised history of MI5 has only a short paragraph – but no Index entry – on Davison, and nothing about him appears in Chapman Pincher’s Treachery, when Pincher himself was responsible, at the time, for revealing uncomfortable information on Davison’s removal in the Daily Express.) I shall therefore just sum up the story here, concentrating on the aspects of his case that relate to espionage and British universities, and how his convoluted story relates to the problems of dealing with questionable employees in confidential government work.

Davison’s pilgrimage to Harwell is even more picaresque than that of Fuchs or Pontecorvo. Boris’s great-grandfather, who was English, had gone to Russia, accompanied by his Scottish wife, in Czarist times to work as a train-driver in Leningrad. They returned to Rugby for the birth of Boris’s grandfather, James (the birth certificate alarmingly states that he was born ‘at Rugby Station’), who was taken back to Russia at the age of two months, in 1851. James married a Russian, and their child Boris was born in Gorki as a British subject, in 1885. The older Boris married a Russian, and the younger Boris was born in 1908. He studied Mathematics at Leningrad University, and graduated in 1930 with an equivalent B.SC. degree.

Davison thereupon worked for the State Hydrological Institute, but, in trying to renew his British passport, he was threatened by the NKVD. Unwilling to give up his nationality, he applied to leave for the United Kingdom in 1938, and was granted a visa. He made his journey to the UK, and succeeded, through his acquaintance with Rear-Admiral Claxton (whom he had met in the Crimea), to gain employment in 1939 at the Royal Aircraft Establishment in Farnborough, working on wind-tunnel calculations. A spell of tuberculosis in 1941 forced his departure from RAE, but, after a year or so in a sanatorium, Rudolf Peierls adopted him for his Tube Alloys project at Birmingham, working for the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. (Avid conspiracy theorists, a group of which I am certainly not a member, might point out that Roger Hollis was also in a sanatorium during the summer of 1942, being treated for tuberculosis.) Davison joined Plazcek at Chalk River in Canada, alongside Nunn May and Pontecorvo early in 1945, and, on his return to Britain in September 1947, worked under Fuchs at Harwell, as Senior Principal Scientific Officer.

The suspicions of, and subsequent inquiries into, Fuchs and Pontecorvo provoked similar questions about Davison’s loyalties, and he was placed under intense scrutiny in 1951, after Pontecorvo’s defection. In a letter to A. H. Wilson of Birmingham University, written from an unidentifiable location (probably the British mission in New York) on May 3, 1944, Rudolf Peierls had written that Davison’s ‘best place would be at Y [almost certainly Los Alamos] provided he would be acceptable there, of which I am not yet sure.’ Davison’s records at Kew state that he was sent to Los Alamos for a short while at the beginning of 1945, but indicate that the New Mexico air had not been suitable for Davison’s tubercular condition, and he had to return to Montreal. It is more probable that Davison’s origins and career would have been regarded negatively by the Americans. (Mountain air was at that time considered beneficial for consumptives.) In his memoir, Peierls also claimed that ‘Placzek wanted Boris to accompany him to Los Alamos, but the doctors doubted whether Boris’s health would stand the altitude. He went there on a trial basis, but after a few weeks had to return to Montreal.’

In any case, Davison was considered a very valuable asset, especially by Cockcroft, who declared that Davison ‘knew more about the mathematical theory behind the Atomic Bomb than any other scientist outside America.’ Nevertheless, or possibly because of that fact, MI5’s senior officers recommended in the winter of 1950-1951 that he should be transferred ‘to a university’. They were overruled, however, by Prime Minster Clement Attlee, who decreed that he should be allow to stay in place. MI5 continued to watch Davison carefully, but when a Conservative administration returned to power in October 1951, questions were asked more vigorously, and Davison was eventually forced to leave Harwell, after some very embarrassing leaks to the Press, and some unwelcome questions from the US Embassy. Hearing about the investigations, they would no doubt have been alarmed that Davison was another who had slipped through security procedures: the Los Alamos visit becomes more relevant. Davison joined Birmingham University in September 1953, and a year later found a position in Canada, whither his wife, Olga (whom he had met and married in Canada), wanted to return. He died in 1961.

This barebones outline (derived from various records in the Davison archive) conceals a number of twists, and raises some searching questions. I have been poring over the reports, letters and memoranda in the archive, and discovered some surprising anomalies and missteps. My conclusion is that MI5’s approach to Davison was highly flawed, and I break it down as follows:

- Lack of rigour in tracking Davison’s establishment in the UK: MI5 never investigated how he passed through immigration, how he provided for himself in the months after he arrived in 1938, how he was able to apply successfully for a sensitive position with the Royal Aeronautical Establishment, how he was allowed to join Peierls’s project supporting Tube Alloys at Birmingham without any vetting, or how he was allowed to join the Manhattan Project in America. He was teased at the RAE because of his poor English, and nicknamed ‘Russki’. An occasional question was posed about these unresolved questions, but it appears that the mere holding of a British passport was an adequate qualification for the authorities.

- Failure to join the dots: When Peierls was viewed as a possible suspect alongside Fuchs in the autumn of 1949, MI5 might have pursued the Peierls-Davison connection. Peierls claimed in his autobiography Bird of Passage that Davison’s name had been sent to him from ‘the central register’ after Davison completed his spell in a sanatorium, although the event is undated. Peierls then recruited Davison. I can find no record of any such communication. There is no evidence that Peierls was ever interviewed over Davison’s entry to the Tube Alloys project, or that MI5 explored potential commonalities in the experiences of Genia Peierls and Davison in dealing with the Soviet authorities. In Bird of Passage, Peierls completely misrepresented the authorities’ inquiry into Davison’s reliability, suggesting that it did not get under way until 1953.

- Ignorance of Stalin’s Methods: MI5 displayed a shocking naivety about the methods of the NKVD. Davison was a distinguished scientist, as the authorised historian of atomic energy, Margaret Gowing, and John Cockcroft both declared. Rather than allow such a person on specious ‘nationalist’ grounds to leave the country to abet the ideological enemy, Stalin would have probably confiscated his UK passport, and forced him to work for the Communist cause. MI5 had failed to listen to Krivitsky, or gather information on the experiences of other scientists ‘expelled’ from the Soviet Union. Instead they trusted Davison’s account of his ‘refusal’ to take Soviet citizenship, even though he gave conflicting accounts of what happened.

- Naivety over NKVD Aggression: One of the experiences related by Davison to MI5 was that, when his passport problem came up, he was asked by his NKVD interrogators to spy on his colleagues at Leningrad University. He declined on the grounds that he was too clumsy to conceal such behaviour, a response that provoked the wrath of his interrogator. Such disobedience would normally have resulted in execution or, at least, exile to Siberia. Yet Davison was ‘rewarded’ by such non-compliance by being allowed to emigrate to his grandfather’s native land, and spread the news. That sequence should have aroused MI5’s suspicions.

- Delayed recognition of the threats of ‘blackmail’: A refrain in the archived proceedings is that Moscow would have been alerted to Davison’s presence at Harwell by Pontecorvo’s defection in the autumn of 1950, and that only then would Davison have been possibly subject to threats. For that reason, his correspondence with his parents in the Crimea (itself a noteworthy phenomenon from the censorship angle) was studiously inspected for coded messages and secret writing. MI5 failed to recognize that the threats to his family would probably have been initiated before Davison was sent on his mission, in the manner that the Peierlses were threatened. (That is an enduring technique: it is reported as being used today by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps.) Since MI5 and the Harwell management realised that Communists had been installed at Harwell for a while, it was probable that the fact of Davison’s recruitment would have reached Soviet ears already. They ignored the fact that his working closely with Fuchs, Pontecorvo and Nunn May meant he would not have needed a separate courier, but they expressed little curiosity in how he would have communicated with Moscow after Fuchs’s imprisonment.

- Unawareness of the role of subterfuge: MI5 spent an enormous amount of time and effort exploring Davison’s contacts and political leanings, looking for a trace of sympathy for communism that might point to his being a security risk. They even, rather improbably, cited the testimony of Klaus Fuchs from gaol, Fuchs vouching for Davison’s reliability, and quoted this item of evidence to the Americans! Yet, if Davison had been a communist, he would probably have preferred to stay in the Soviet Union, helping its cause, rather than taking on a role in provoking the revolution overseas, something for which his temperament was highly unsuited. Even if the lives of his parents had not been threatened, his most effective disguise would have been to steer clear of any communist groups or associations.

- Clumsy handling of their target: MI5 and Harwell – and, especially, John Cockcroft – showed a dismal lack of imagination and tact in dealing with Davison. Cockcroft was weak, wanted to hang on to Davison because of his skills, and avoided awkward confrontational situations. They failed to develop an effective strategy in guiding Davison’s behaviour, and Cockcroft, when trying to encourage Davison to leave Harwell, even suggested that he was entitled to have a government job back after his one-year ‘sabbatical’, because of his civil servant status. Between them, Harwell and MI5 deluded themselves as to how the account of a Russian-born scientist expelled from Harwell would manage not to be re-ignited, through idle gossip, or careless bravado (as turned out to be the case).

- Simplistic views of loyalty: MI5’s perennial problem was that it did not trust ‘foreigners’, and had no mechanism for separating the loyal and dedicated alien from the possibly dangerous subversive, or taking seriously the possible disloyalty of a well-bred native Briton. Davison fitted in to no established category, and thus puzzled them. In his letter to Prime Minster Attlee of January 12, 1951, as Attlee was just about to make his decision as to whether Davison should remain in place, or be banished to a university, Percy Sillitoe wrote that ‘an alien or a person of alien origin has not necessarily enjoyed the upbringing which, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, normally ensures the loyalty of a British subject’, a sentiment that Attlee echoed a week later. Four months later, Burgess and Maclean defected.

MI5 were not happy with Attlee’s decision, wanting Davison safely transferred to academia. They were worried stiff that, if any action were taken, Davison ‘might do a Pontecorvo on us’, and that in that case closer cooperation with the Americans – an objective keenly sought at the time – would be killed by the Congressional committee. They thus hoped that matters would quieten down, and that Davison would behave himself. Yet a meeting held in February 1951 with the Prime Minister provoked the following minute: “Rowlands, Sillitoe and Bridges agreed there should be discussion on the proposition that Davison should be asked what his reactions would be if the Russians brought pressure on him through his parents. If approach were made, Davison would mark it as a mark of confidence in his own reliability.” What the outcome of this strange decision was is not recorded, but the threat to MI5’s peace of mind would turn out to come from friendlier quarters.

- Boris Davison – after Attlee

Attlee made his decision on February 20, 1951. Sillitoe requested a watch be kept on the Skinners in Liverpool. Meanwhile, MI5 officers had a short time to reflect on Davison’s background. Dick White wondered who the other ‘Britishers’ who were deported at the same time as Davison were, and what had happened to them. (Whether this important lead was followed up is not known: the results might have been so uncomfortable that the outcome was buried.) Yet Reed was later imaginative enough to wonder how Davison ‘was able to survive the purges and outbreaks of xenophobia’, suggesting perhaps that further lessons had been learned. “What services were rendered in exchange for immunity?”, he asked, but there the inquiry ended, for 1951 turned out to be an annus horribilis for the Security Service, as the uncovering of the Burgess & Maclean scandal showed the authorities that espionage and treachery were not simply a virus introduced by foreigners. For a while it distracted attention from the quandary of suspicions persons in place at Harwell.

By that time, however, a series of events began that showed the Law of Unintended Consequences at work. In February, Chapman Pincher had written a provocative article about Pontecorvo in the Daily Express, and on March 4 Rebecca West had published an article about Fuchs, critical of Attlee, in the New York Times. Perrin and Sillitoe agreed that a counterthrust in public relations was required, and conceived the idea of engaging the journalist Alan Moorehead to write a book that would reflect better on MI5’s performance. After some stumbles in negotiation, Moorehead was authorized to inspect some confidential information on September 24, and started work.

The year 1952 progressed relatively quietly. John Cockcroft had revealed to Skinner in early 1951 that he was considering recommending the South African Basil Schonland as his successor, and was perhaps surprised to be told by Skinner that Schonland was not up to the job. This was surely another indication that Skinner felt himself the better candidate, and wanted to return to Harwell now that Fuchs and Pontecorvo were disposed of. A possible opening for Cockcroft appeared in March 1952 at St. John’s College, Oxford, but nothing came of it. On July 29, Sillitoe announced he would retire at the end of the year. In August, Davison indicated for the first time that he wanted to leave Harwell. And in September, as I described earlier, Skinner’s controversial review of Moorehead’s finished work The Traitors came to the attention of Arnold and MI5.