Sid said, ‘I hate conspiracy theories.’

‘It’s not a theory once it’s proved. After that, it’s just a conspiracy.’

(from ‘Slow Horses’, by Mick Herron)

Contents:

Background and Introduction

Guy Liddell’s Behaviour

Part 1: Peter Wright & Constantin Volkov

Nigel West’s Molehunt

Gordon Brook-Shepherd’s Storm Birds

Phillip Knightley’s Master Spy

Keith Jeffery’s Postscript

The National Archives

Nigel West’s Cold War Spymaster

The Volkov Text

Part 2: Peter Wright & Double Agents

Nigel West & Double Agents

Conclusions

Background and Introduction:

It was a year ago (WhoFramedRogerHollis?) when I presented my case that the investigation into Roger Hollis in 1963 was an elaborate set-up by Dick White and Arthur Martin. Yet I know, from communications I have received from coldspur readers, that the belief that there was an MI5 mole active in the 1950s and 1960s, that he (or she!) was known as ‘ELLI’ by the KGB, and that ELLI was probably Roger Hollis, dies hard. In this segment I return to inspect some of the symptoms of betrayal that encouraged Martin, and, more specifically, his faithful sidekick Peter Wright, to pursue their quest to unmask this sinister figure.

The prevailing ‘wisdom’ is that a traitor working at the highest levels of MI5 was responsible for the failure of multiple counter-intelligence operations of the Security Service. For example, the careful and methodological study sponsored by the FBI, ‘British Patriot or Soviet Spy? Clarifying a Major Cold War Mystery’ (see https://fbistudies.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/20150417_ReportandChronologyHollis.pdf) , using ‘argument mapping’ to bring some discipline to the study, starts off by introducing the contention: ‘There was a GRU mole in MI5 between 1940 and 1945 under the codename ELLI’. It then breaks this assertion down into the various claims made by defectors, including Gouzenko and Akhmedov. But it immediately gets bogged down into a misunderstanding about what Gouzenko said, a misinterpretation of the exchange between Philby and Moscow Centre, and then introduces the distracting testimony of Christopher Andrew (who declined to attend the session) with his erratic statement that ELLI did exist, but was in fact Leo Long.

Overall, this study was far too much influenced by Chapman Pincher’s fanciful and unverified tale displayed in Treachery. Yet the project claims to be off and running on the basis that the GRU did operate a spy in MI5 alongside the KGB’s Anthony Blunt. “There is complete acceptance that, in fact, it was penetrated by both the KGB and the GRU”, the report confidently maintains. But that is not so. Even Christopher Andrew writes, in Defend the Realm (p 350): “A series of conspiracy theorists, chief among them the maverick MI5 officer Peter Wright, succeeding in convincing themselves and many of their readers that ELLI was none other than Roger Hollis, who had been working as a Soviet agent throughout the Gouzenko investigation.” But thereafter, Andrew and I part company.

As I have shown in my previous writings, the story about ELLI was probably based on a misunderstanding between the MI5 officer Stephen Alley and Colonel Chichaev, the Soviet military attaché installed in London at the same time that the SOE/MI6 mission to Moscow was established, at the end of 1941. Alley (who spoke Russian, and was thus responsible for ‘handling’ Chichaev) probably made a light-hearted remark about his old colleague George Hill, the head of the mission (who had just made a visit to London on leave) and Hill’s reacquaintance with a former agent of his from revolutionary days, whom the NKVD had attempted to plant on him. Chichaev surely felt duty-bound to report this conversation to his superiors, and word got around that Hill had a spy in Moscow, something that Gouzenko picked up in his role as a cipher clerk.

Guy Liddell’s Behaviour:

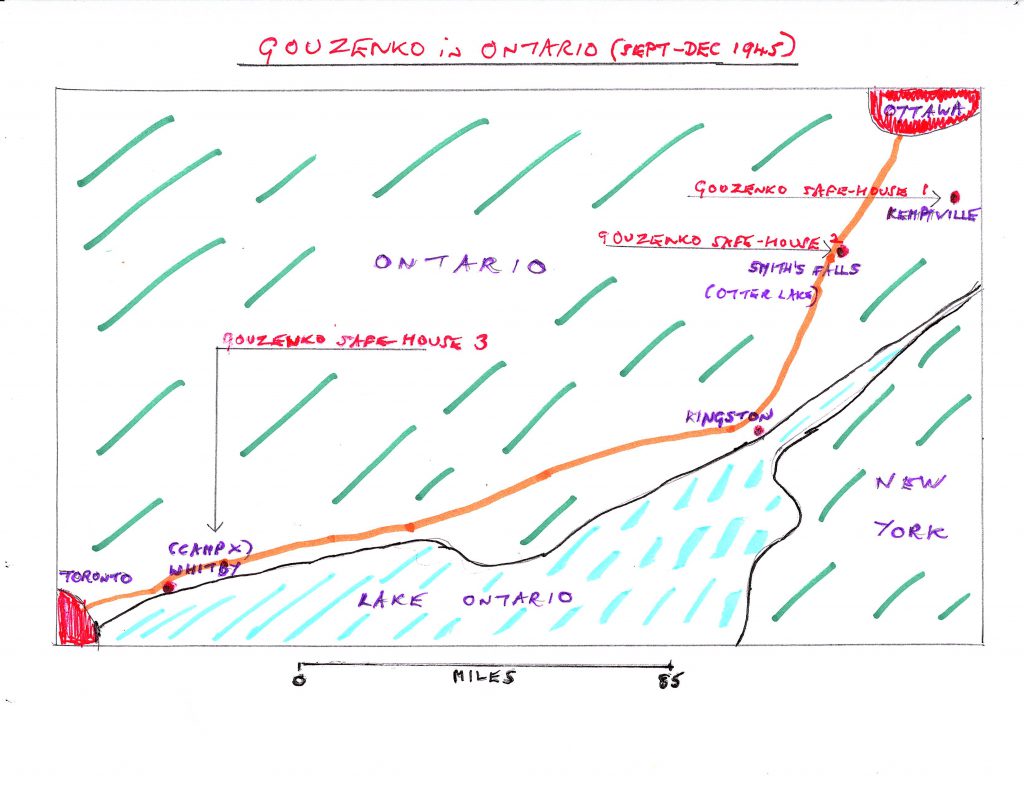

Guy Liddell’s thoughts at the time are very pertinent. As I have reported before, he even recorded in his diary the possibility that ELLI might be Alley, but then immediately discarded the notion as too preposterous – simply because he was confident of Alley’s utter loyalty. At the time, however, he was still investigating who ELLI was, and, firmly of the belief that he was an SOE asset (as other conversations made clear), started deeper research by working with the SOE Security chief, Archie Boyle. From the way the topic suddenly drops from his diary entries, we could assume that the culprit was soon identified, and the case casually dismissed, or, alternatively, that the revelations were so horrifying that he tried to place a blanket over the whole business. What is also extraordinary is the fact that Liddell interviewed Gouzenko in March 1946, yet, according to what he reported, he never brought up the question of ELLI, nor did Gouzenko volunteer any information about the spy and his cryptonym.

Yet ELLI did not die away: the Americans knew about the whole business, and resuscitated the question a few years later. Liddell’s diary entry for October 1, 1951 (when Philby had come under suspicion after the absconding of Burgess and Maclean) records that Bedell Smith (the head of the CIA) had told Stewart Menzies, the MI6 chief, after having a meeting with Liddell’s boss Percy Sillitoe ‘that he thought that MI5 were now confident that Philby was identical with the man mentioned by Gouzenko and Wolkov’ [sic: more regularly ‘Volkov’, the NKGB officer who tried to defect from Istanbul]. Liddell observes that Bedell Smith must have misunderstood what Sillitoe was telling him at their recent meeting. “This is of course far from the case”, he adds, laconically. ‘Of course’? It sounds as if the ELLI business has been sorted: ELLI’s identity was known, and it was not Philby. And, ‘of course’, Sillitoe might have got it wrong himself – or might have intended to send Bedell Smith away with a false trail.

So what might Liddell’s studied avoidance of the ELLI business in 1946 have meant? I consider four possible explanations: Indifference; Resolution; Resignation; and Dismay. I believe that Liddell took the allegations of espionage seriously, but that his sensibilities had been softened by his experience of Blunt and Long during the war, where he probably attributed their passing on of confidential information to the Soviet Embassy to an over-zealous desire to help Stalin in the war effort. On the other hand, if he regarded the ELLI problem as resolved, and believed that the threat had been uncovered as being non-existent, and was all due to a misunderstanding, he never communicated it to those whose opinion mattered, such as the Americans. He also did not consider any investigation a waste of effort. Ever since Krivitsky, it is true, MI5 had had to deal with allegations of spies inside British government, and the fresh claims made by Gouzenko and Volkov were simply part of a pattern, which could conceivably have been of exaggeration or provocation. While there were no real leads to follow up, and the effort was time-consuming, Liddell stayed alert to the threat.

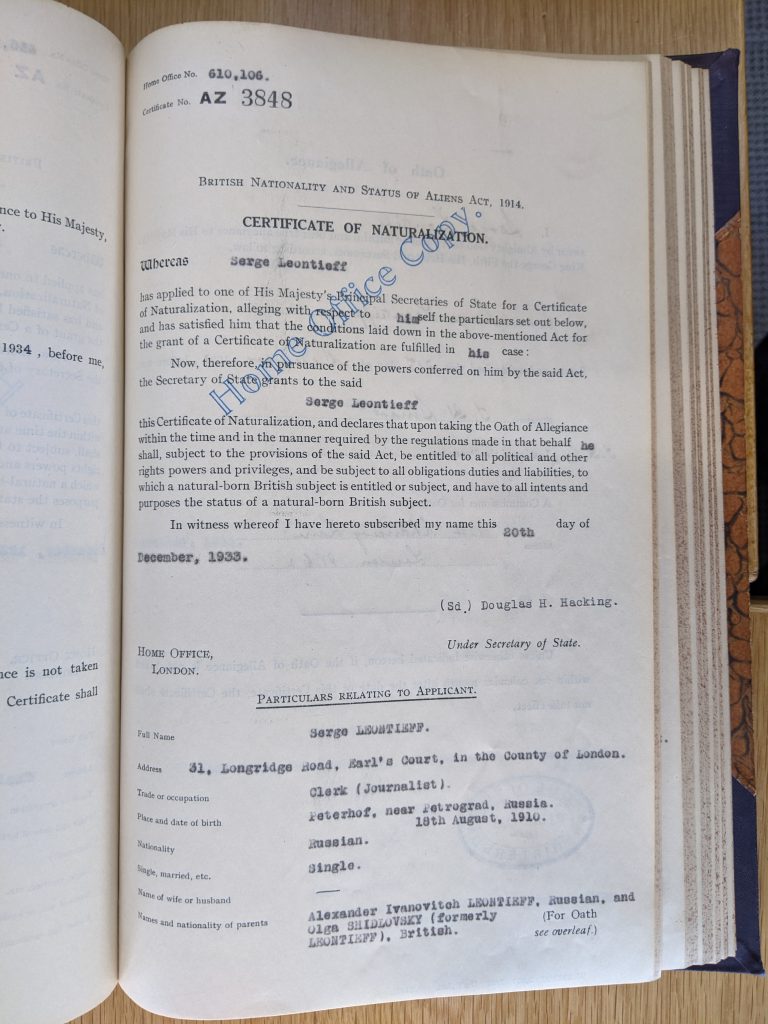

I suspect that the real reason for his silence was Dismay. The search for ELLI revealed such shocking mismanagement and exposures to British security that Liddell tried to hush up any investigative process.When he pursued the investigation into SOE, and discovered the alarming fact that a White Russian (Sergey Leontiev, aka George Graham) had been introduced as a cipher clerk into the Soviet SOE mission, and had been left unattended in Kuibyshev, he closed down the investigation, as the discovery showed a far more dangerous exposure than any ELLI might have caused.

(At another time I shall investigate the serious breaches of security that must have been occasioned by the subornation of George Graham, introductory details of which can be read at TheStrangeLifeofGeorgeGraham. For instance, in early 1945, he was copied in on Foreign Office telegrams concerning the search for members of SOE believed to have been arrested by the Germans, some with strict instructions that the Russians not be informed of the inquiries, as some agents were born in the Soviet Union. Gordon Brook-Shepherd [see below] has correctly pointed out – without showing any understanding of the George Graham fiasco – that the Kremlin would have been aware, before the Teheran, Yalta and Potsdam summits, of what the negotiating positions of the Western Allies were.)

Thus the tensions in the investigation lie between the allegations of Gouzenko (who pointed to ELLI, but never indicated Philby), and the accusations of Volkov (who never got so far as to offer any cryptonyms such as ELLI, but who pointed to Philby). All those who have written about the case have twisted themselves into knots over the sources and the evidence. My task in this bulletin is to inspect the sequence of events that brought the Volkov story to the attention of the British public, and the steps by which it evolved. The whole charivari constitutes an extraordinary procession of self-delusion, negligence, and deception. In it, the role of Peter Wright is critical, for the following reasons: i) the enormous popularity of Spycatcher; ii) the attempts by Her Majesty’s Government to ban it; iii) Wright’s influence on Chapman Pincher, and the latter’s persistent accusations against Roger Hollis; and iv) the highly unmethodical nature of Wright’s analysis. I thus focus on the pivotal disclosures and speculations of Wright, although the account goes backwards and forwards in time.

Peter Wright’s narratives about agents and double-agents are not the only ‘evidence’ he presents to support his case that MI5 had a mole in its upper echelons. For example, he dedicates the whole of Chapter 10 of Spycatcher to the Gordon Lonsdale/Krogers affair, and concludes that all the inconsistencies of the case pointed unmistakably to the fact that the Soviets were being informed of what was going on. Yet the obvious truth is that, if someone had been making the Russians aware of how the investigation was progressing, the KGB would surely have subtly removed Lonsdale (Konon Molody) from London, and the Krogers’ spynest in Ruislip would never have been discovered. In his whittling down of the various allegations of penetration to the ten most important (p 278), Wright lists Volkov’s ‘Acting Head’ feed, and Gouzenko’s claims about ELLI, both in September 1945, as Number One and Number Two. Having investigated the Gouzenko story in depth in earlier posts, I now concentrate on the first of these two items.

Part 1. Peter Wright & Konstantin Volkov:

Before analyzing Volkov’s major allegations about Soviet penetration that the molehunters in MI5 turned their attention on, I want to study the vexed issue of the breaking of Foreign Office ciphers. Konstantin Volkov had highlighted this security lapse in the dossier that he provided to the British Consulate in Istanbul. Volkov was an NKVD officer in Turkey who, in August and September 1945, had approached officials at the British consulate with promises of information about Soviet agents (see https://coldspur.com/on-philby-gouzenko-and-elli/). At the time that Peter Wright wrote of the business in 1986, in Spycatcher, official documentary support for what Volkov told the members of the consulate was not available: much of what was written about him derived from Kim Philby’s memoir issued in 1968, My Silent War, which cannot be regarded as an overall reliable testament, and from some journalism that had incredibly been overlooked. (For those readers unfamiliar with the Volkov story, Kim Philby was the MI6 officer eventually sent out to Ankara to deal with Volkov, who had been predictably spirited away by the NKGB * by the time Philby arrived.)

[* The NKGB was created in 1943 as a separate directorate from the NKVD, but reconstituted as a ministry, the MGB, in 1946.]

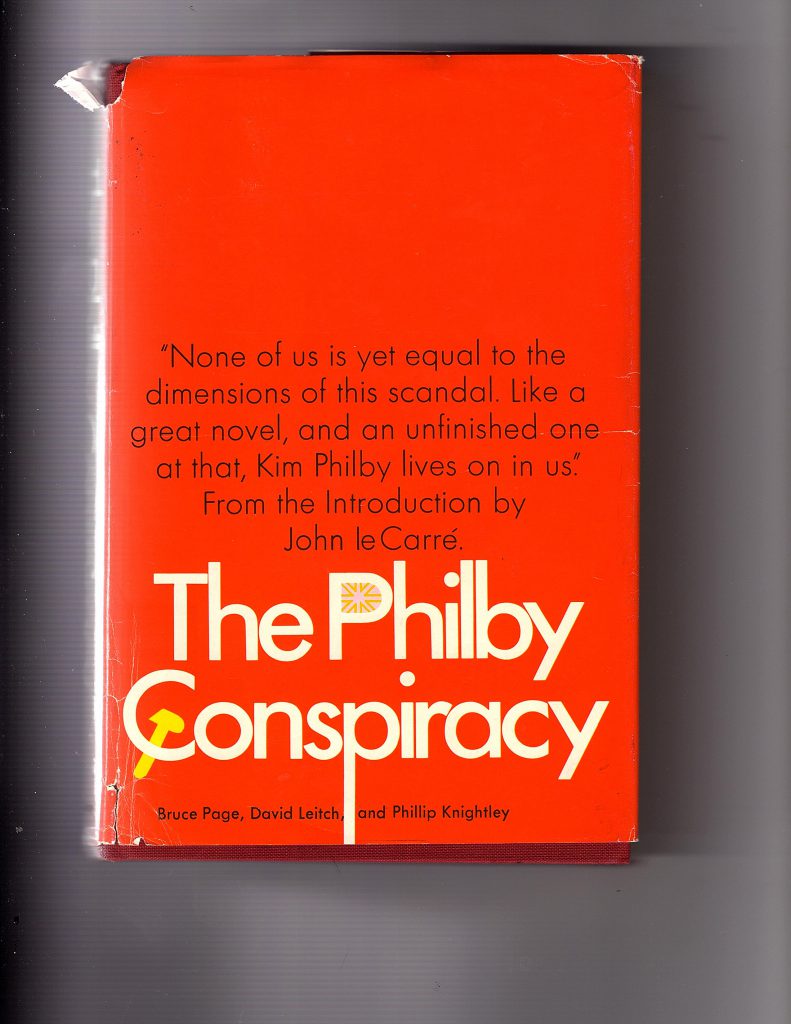

Another narrative was available, however. In 1968, the Sunday Times Insight team of Bruce Page, David Leitch and Phillip Knightley had published The Philby Conspiracy, which was based on several hundred interviews with various diplomats, intelligence officers, etc. It regrettably had no sources listed (because of the Official Secrets Act), and avoidably no Index. Integrating the essence of hundreds of anonymous and unverifiable interviews, when the subjects may well have been dissembling, is not a path to good history-writing, but The Philby Conspiracy was a valiant effort to pierce through the fog. As it turned out, John Reed could have been unerringly identified as the primary source for the narrative about the Volkov affair – alongside Philby’s memoir. The Insight production could stand for a while as a reasonably accurate account of the Volkov business.

In his account of the Volkov affair, Peter Wright focused first on the cipher leak. He stated:

During the course of the inquiry I was also able to solve one other riddle from Volkov’s visit. Volkov claimed that the Russians could read the Foreign Office ciphers in Moscow. Maclean certainly betrayed every code he had access to in the Foreign Office, but Foreign Office records showed that the Moscow Embassy used one-time pads during and just after the war, so Maclean could not have been responsible.

Remembering my work with “the Thing” in 1951, I was sure the Russians had been using a concealed microphone system, and we eventually found two microphones buried in the plaster above the cipher room. During the war, two clerks routinely handled the Embassy one-time pad communications, one reading over the clear text message for the other to encipher. The Russians simply recorded the clear text through their microphones. By the very good work of the Building Research Laboratory we were able to establish that the probable date of the concrete embedding of the microphone was about 1942, when the Embassy was in Kuibyshev.

Now, to me, that sounds like a highly improbable method of addressing the delicate task of encrypting messages, but I shall not strenuously argue the point here. Wright went on to write, however, that ‘the Working Party Report found an extraordinary and persistent level of appalling security inside the Embassy’, which resulted in the demand that an MI5 officer should work full-time there on security matters. It is not stated what the problems were, but if the Working Party concurrently discovered the same egregious lapses in recruitment and management that Liddell came across, it would point not to mechanical intrusion by the NKVD (although that surely did occur), but more to human treachery, with the unfortunate George Graham suborned by the honey-trap, and consequently forced to hand over cipher details.

On the other hand, that procedures were not quite as Wright depicted can be learned from other sources. In his memoir of the time, George Hill wrote, of his few months in Kuibyshev (where all foreign missions had been moved at the end of 1941, owing to the German advance on Moscow):

We, Guinea Pigs, day and night have been helping the Embassy in coding up and decoding messages, for the volume of work has increased beyond the powers of the regular staff, caused by the latest events, besides doing our own stuff. Even I am beginning to get quite fast at coding.

Not ‘one clerk reading out a clear text to another’, then. Moreover, the Embassy and SOE Mission were housed at the Kuibyshev Boy’s Gymnasium School, evacuated for the purpose, so it is not clear that the NKVD had had time to wire the premises before the arrival of the British. In addition, in his account of Volkov’s statement quoted above, Wright stressed that the Soviet electronic interception occurred in Moscow, not Kuibyshev. He makes a giant illogical leap in transferring the detection to the city 1,000 kilometres away. Yet this was his area of special expertise: according to Nigel West, Wright’s entry to MI5 had been guaranteed by the skill he showed in detecting, in 1952, that a microphone had been inserted in a seal behind the US Ambassador’s desk in Moscow. Thus that may be a reason he concentrated on technology rather than human agency.

As I reported a few months ago, the security lapse occurred when Hill left Graham behind in Kuibyshev, where the Mission did not even own a locked safe to store the codebooks overnight. (The Chubb safe had had to be left behind in Moscow.) Thus we have a far more convincing explanation of what Volkov was referring to when he spoke of security lapses, and urged his contacts in the Istanbul consulate not to use cables in transmitting his accusations about Soviet subversion of the Foreign Office and British Intelligence, but instead pass them on in the diplomatic bag. (As readers will learn later in this piece, the officials in Istanbul did not follow this guidance punctiliously.)

Wright then moved on to the hints at London-based agents provide by Volkov. One of the controversial statements that Philby had made ran as follows:

He [Volkov] also offered details of Soviet networks and agents operating abroad. Inter alia, he claimed to know the real names of three Soviet agents working in Britain. Two of them were in the Foreign Office; one was head of a counter-espionage organisation in London.

Philby immediately recognized himself as the organisation head, and, after a minor panic, set about extinguishing the threat. Wright then expanded on this version of events.

In describing the NKVD officer’s approach to the British Consulate, where he said that he could provide names of Soviet spies in Britain if he were paid adequately, Wright had written (p 238) that Volkov ‘gave an Embassy official a list of the departments where the spies allegedly worked’, as well as a hint to an MI6 spy in Persia. Wright then jumped (p 278) to highlighting Volkov’s claim (one of the ten ‘really important allegations’ from defectors) that one of the spies was an ‘Acting Head’, without offering any details of where that nugget derived, something he echoed on p 285. Only then did he inform his readers that Volkov’s list of spies ‘talked of seven in London, two in the Foreign Office, and five in British Intelligence’. While this version was clearly different from the Philby story, the revelation allowed him to identify Burgess as one of the pair. For some reason, however, he discounted Maclean, arguing that, since he was not in London at the time, he could not be the candidate. (This must be the sole occasion when the indivisibility of ‘Burgess and Maclean’, etched into British cultural history like ‘Marks and Spencer’ or ‘Morecambe and Wise’, has ever been challenged.) Wright ignored the fact, however, that Volkov may not have been completely up-to-date on the movements of these persons. Moreover, ‘in London’ could simply mean ‘working for a British institution’.

Wright then turned to British Intelligence:

But what of the five spies in British Intelligence? One was Philby, another was Blunt, and a third Cairncross. Long might theoretically have been a fourth Volkov spy, but he was not in London at this time, and he could not possibly be one of the eight VENONA cryptonyms, since he was in Germany in September 1945. That still left one Volkov spy, the ‘Acting Head’ unaccounted for, as well as four VENONA cryptonyms, of which presumably the ‘Acting Head’ was one, and Volkov’s second Foreign Office spy another. As for ELLI, there was no trace of him anywhere.

This analysis is a bit of muddle, with Wright mixing up VENONA sources with Volkov’s submissions. Moreover, he overlooks candidates such as Milne, Klugmann, Uren, or even James Macgibbon, all at some time in departments of ‘British Intelligence’, whose cryptonyms may have caught Volkov’s eye. Yet the fact that there was a total of seven spies in London, of whom two were in the Foreign Office, had nevertheless taken hold.

Nigel West’s Molehunt:

The following year, Nigel West published his Molehunt. He reminded readers that it was Philby who had first claimed in My Silent War that Volkov had mentioned ‘two Soviet agents in the Foreign Office, one head of a counter-espionage organization in London’, but West did not immediately draw attention to the discrepancy between Philby’s version and that of Wright. Had they both been reading from the same Volkov letter, one wonders? Somewhat mysteriously, West elided this paradox, but went on say that ‘a check was made on the text of the first message as received from Istanbul’, and he followed with:

It was compared with the original which had been typed by Volkov and handed in to the British Consulate before his disappearance. A slight discrepancy was noted in Volkov’s Russian original. He had mentioned a total of five agents in British Intelligence and two in the Foreign Office. However, the translation of a crucial sentence read, “I know for instance that one of these agents is fulfilling the duties of Head of a Department of British Counterintelligence.”

This statement seems to me unsatisfactory and evasive: it provides no dates; it deploys too much use of the passive voice and does not explain who was doing the comparisons, the inspections, and the translations; it provides no documentary evidence. Had West had access to MI5 files? No: his source is given as ‘Peter Wright, World in Action’, a television programme broadcast on July 16, 1984.

So why should West trust Peter Wright, and why did Wright not explain this process in Spycatcher? West draws attention to the fact that Philby interpreted the incriminating description as referring to himself, but Wright had other ideas. As West goes on to write:

Philby’s treatment of this vital passage was interesting because his record omitted mention of the five moles in British intelligence and implied that the “Head of a Department of British Counterintelligence” was a reference to himself. Certainly, Philby was then head of Section IX, a counterintelligence department of SIS. The point was pursued by Terence Lecky and Wright, with further help from GCHQ’s Russian-speaking expert who made a new attempt to translate Volkov’s original message. The second translation altered its accepted meaning by reinterpreting the critical sentence to read. “I know for instance that one of these agents is fulfilling the duties of acting Head of a Department of the British Counterintelligence Directorate.” Wright believed that far from implicating Philby, who had served in SIS, Volkov had actually been referring to someone in MI5. The “Head of a Department in British Counterintelligence” might well be said to refer to SIS, but there could be no mistaking the author’s intention when he mentioned the “British Counterintelligence Directorate”.

This again strikes me as undisciplined. West does not question why Lecky and White were suspicious that the text may have been mistranslated, nor does he call on the letter itself to be shown as evidence. Was Philby being obtuse, trying to conceal the extent of Soviet infiltration? Was he throwing the item about two Foreign Office spies in the face of his ex-colleagues, calling them out for their feebleness in not following up on Volkov’s leads? West does not speculate. Yet he has no grounds for accepting the ‘new’ translation. He simply trusts what Wright tells him, when the actions of Lecky and Wright show all signs of regrettable a priori thinking. In fact, when Sir Burke Trend was invited to go over all the FLUENCY papers, Trend challenged Wright on the reworking of Volkov’s allegation. “Wasn’t I being finicky in altering the thrust of the allegation after having the document retranslated? He asked”, wrote Wright (p 380). ‘Finicky’? That was an odd adjective to use in the circumstance. Wright’s answer was not profound:

“I don’t see why,” I replied. One way is to make guess about what an allegation means, and where it leads, and how seriously to take it. The other way is to adopt a scholastic approach, and analyse everything very carefully and precisely and build scientifically on that bedrock.”

Philby had appeared as a clear candidate for what was superficially an accurate job description. There was really no guesswork involved. Nevertheless, Wright then reportedly had Golitsyn check out the Russian text, and the defector agreed with the new interpretation. And that led to the ‘proof’ that there was a mole in MI5, and the investigations into Mitchell and Hollis. This was all very unsatisfactory. What was direly needed was an inspection of Volkov’s original letter. How could a simple statement have been phrased so poorly that it gave rise to such ambiguity? Yet instead of some proper archival evidence, the world gained another less than disciplined narrative.

Gordon Brook-Shepherd’s Storm Birds:

Three years later a book with the trappings of a more authoritative account of the Volkov affair appeared on the scene. Gordon Brook-Shepherd was a former asset of MI6 who had previously published a book on early Soviet defectors, titled The Storm Petrels. In 1989 he issued a follow-up, titled The Storm Birds, which studied post-war Soviet defectors, carrying the engaging sub-title The Dramatic True Stories: 1945-1985. It is a useful but in many ways a complacent and erratic work. Not all his subjects were even defectors: for example, Penkovsky and Farewell (Vetrov, whom he does not name) were agents-in-place who were executed before they could defect, and Volkov never managed to complete his defection. The chapter on Lyalin has no sources listed.

While Brook-Shepherd’s judgment is overall sound (for example on Penkovsky and Golitysn), he frequently offers no explanation as to where his intelligence comes from, with a paucity of Footnotes to describe his sources. This is especially true of Chapter 4 (The Wrecker), where the author covers Volkov. Brook-Shepherd provides a Bibliography that reflects his opinions on many relevant works of interest, but in his Foreword introduces his distinctive qualifications for documenting his tale of defectors in the following terms:

For the present work, I have been able to talk at length, either in America or Europe, to no fewer than eight Soviet defectors. Their accounts have been corroborated and amplified by expert sources in Europe and America.

That was not adequate, however. Volkov had been executed in 1945, and was not subject to interview, yet Brook-Shepherd had somehow been able to provide a comprehensive account of the approach by the NKVD officer to the British legation.

Nevertheless, Brook-Shepherd still suggests authoritativeness in passing on the full details of Volkov’s approach in Istanbul. He gives the names of the officials involved, describes the delays that occurred, and records the eventual dispatch of Philby to address the situation. He refers to the 314 Soviet agents in Turkey and the 250 in Britain that Volkov claimed he could name, and also cites the numbers of two spies in the Foreign Office and seven inside the British intelligence system. He identifies John Reed as the officer who acted as interpreter. Brook-Shepherd notes the critical phrase from the translation of Volkov’s letter (that one was ‘fulfilling the function of head of a section of British counterespionage in London’) with a cautious aside, namely that ‘the counterespionage official (the Russian phrase had been difficult to translate precisely) was probably Philby, although the description could have fitted Roger Hollis’. Given that Brook-Shepherd, in his Foreword, states that the evidence from the case of Colonel Penkovsky ‘destroys by itself the thesis that Sir Roger Hollis could have been a Soviet agent’, this was a somewhat equivocal attitude to adopt. He suggested, by his comment, that he was familiar with Peter Wright’s investigation into the meaning of the controversial passage, but he did not list Spycatcher in his Bibliography, merely criticizing Chapman Pincher’s books for ‘relying much too heavily on the reminiscences of one long-retired former MI5 officer, Peter Wright of Spy Catcher fame [sic]’. It is an uneven performance.

On the other hand, Brook-Shepherd did sensibly highlight the breach in ciphers, and recorded the revelation as follows:

There was one more startling piece of information, which was to complicate fatally the transaction. For the last two and a half years, Volkov assured his listeners, the Russians had been reading all cipher traffic, both on the normal diplomatic channel and on the special intelligence ones, which had passed between the British embassy in Moscow and London. (This claim was never verified but, in view of Volkov’s service inside the Moscow Centre, was taken very seriously. It would have meant, for example, that the Kremlin had been aware, before the Teheran, Yalta, and Potsdam summits, what the western negotiating position was.)

It may be significant that Brook-Shepherd here refers to both ‘diplomatic’ and ‘special intelligence’ channels, whereas Wright had described the exposure solely as a ‘Foreign Office’ breach. Was Wright being coy, or merely forgetful? It is hard to say. Yet, as I shall show later, Brook-Shepherd’s observation about the seriousness of the response is very provocative, and needs to be challenged in the light of other evidence. He was correct in drawing attention to the seriousness of this allegation, but apparently overlooked a vital commentary.

As far as I can establish, no one appeared to question Brook-Shepherd, or show much interest in his sources. In KGB: The Inside Story, published in 1990, Christopher Andrew and Oleg Gordievsky were happy to echo Brook-Shepherd’s telling of the story, indicating in an Endnote that they believed that Brook-Shepherd’s account was the ‘most reliable’, and corrected ‘a number of inventions by Philby’. (Through this gesture they appeared to cock a snook at the Sunday Times’s journalistic venture. Brook-Shepherd and Andrew were generally dismissive of Knightley because of the errors he perpetrated in his book The Second Oldest Profession.) This statement constituted a less than subtle indication that they alone knew the full facts, and that they could therefore impart to their readers how accurate (or inaccurate) both Philby and Brook-Shepherd were, while not divulging wherefrom their wisdom derived. Under this guise, they were able to discriminate, trusting (for instance) Philby’s description of his dealings with his handler, Krotov, while dismissing part of what he wrote as fantasy. Gordievsky was surprisingly not able to provide much new insight on the affair at this stage.

And Brook-Shepherd’s authoritative-sounding story (which happened to mesh quite closely with how Philby had described the events) remained a point of orientation for the world at large for several years. It had to wait a while for another oracular statement from on high for his chapter to be granted the seal of approval, namely an Endnote in Andrew’s Defend the Realm, published two decades later. Having outlined the events in a summarization of Brook-Shepherd’s account (pp 344-345), without indicating that any intelligence archives had been inspected, Christopher Andrew echoed his previous assessment when he wrote: “The most reliable account of Volkov’s attempted defection is in Brook-Shepherd, Storm Birds, pp 40-53, which corrects a number of inventions and inaccuracies in Philby’s version of events.” This was a typically patronizing and disingenuous observation by Andrew, since he still did not deign to explain why he considered Brook-Shepherd’s account so trustworthy. I have to conclude that Andrew had been informed by his political masters that Brook-Shepherd had been guided to the appropriate archives, in the same manner by which M. R. D. Foot had been steered by the SOE Adviser. But the whole business was very shabby and unprofessional.

Phillip Knightley’s Master Spy:

As a further manifestation of the extraordinary manner in which false trails are led, and real ones ignored, in this business, I must include the episodes involving the journalist Phillip Knightley, as a kind of parallel path to what his Insight team was doing at the Sunday Times. As early as October 1967, the London paper, which had been investigating Gouzenko’s claims about ELLI, and whether they referred to Philby, received a hint from one Leslie Nicholson, who had worked for MI6, and written a book titled Secret Agent under the name John Whitwell. Nicholson revealed to Phillip Knightley that Philby had led the service’s Soviet counter-espionage unit – a fact that impressed the newspaper team. Why Knightley and co. should have found this insight a breakthrough is itself a puzzle, as Philby had explicitly described in his memoir how he had managed to install himself as head of Section IX, which was responsible for Soviet counter-intelligence. That aside, finding the irony of a possible Soviet agent heading a British counter-intelligence unit supremely appealing, the newspaper published an article on Philby on October 1, 1967 – its first on the alleged traitor. The appearance of the piece had a rewarding outcome, however. It provoked John Reed, the interpreter at Istanbul, and currently the Sheriff of Shropshire, to write a letter to the editors. Part of it ran as follows:

I am wondering whether next week’s issue will mention an incident which occurred in Istanbul in August 1945 and in which both Philby and I were involved. If so, and I am mentioned by name, I should be grateful for a preview of the text before it is published. The incident convinced me that Philby was either a Soviet agent or unbelievably incompetent and I took what seemed to me at the time the appropriate action.

Excited by these revelations, which enabled them ‘to crack the one aspect of the Philby story that had eluded them’, the Sunday Times journalists published Reed’s story the following week. (Strangely, The Philby Conspiracy does not carry this incident.) What was astonishing about the fresh revelations is that Reed was clearly not concerned about being identified as the ‘leaker’, and obviously felt that any doubts or remonstrations he had maintained about Philby’s loyalty had not been taken seriously. The essence of Reed’s testimony is recorded in Knightley’s book, The Master Spy, which came out in 1988. The story is essentially the same as the one that Brook-Shepherd told, yet the fact that Reed had spoken out, and that his observations as a key witness and facilitator had appeared in the national press over two decades beforehand, was ignored by Brook-Shepherd – as well as by those who came after him.

Yet Reed’s behaviour is also a bit puzzling. In his letter, he claimed that he took what seemed to him the appropriate action. This involved a direct challenge to Philby, which resulted in the infamous statement about ‘leave arrangements’ interfering with London’s response. Philby’s account indicates he was able to manipulate Reed. He writes, of his need to ‘get Volkov away to safety’ (a horribly macabre way of putting it, incidentally):

I thought that I could string Reed along further by hinting that we were by no means satisfied that Volkov was not a provocateur. It would be most unfortunate, therefore, if his information was given currency before we could assess his authenticity. I felt that I could do no better. An expert, of course, could have driven a coach-and-four through my fabrications. But Reed was not an expert, and he might prove pliable.

But did Reed voice his concerns up the line? It is not clear. Knightley’s account runs as follows:

Later Reed took the opportunity at a diplomatic reception to pass on his suspicion to a colleague from the American Embassy in Ankara, but this was before the CIA had been created. OSS was winding down, and Reed’s American colleagues had no intelligence contacts, so it is unlikely that the story got back to Washington in a form that could do Philby any harm. SIS itself accepted Philby’s theory about Volkov’s insistence on bag communications, so his luck held out.

It would have been highly unprofessional and irresponsible for Reed to have expressed his doubts about Philby to the Americans, but not to his own bosses at the Foreign Office, yet this testimony came from Reed himself. Had he in fact sent in a report, and was he out of sensitive political concerns covering for the Foreign Office mandarins, and maybe protecting his pension, from his retreat in Shropshire?

The historian Edward Harrison helped provide an answer. When researching his own book on Philby, he dug out a letter in the Dacre (Trevor-Roper) papers at Christ Church, Oxford that indicated that Reed had probably overstated his suspicions. Reed had written to Trevor-Roper in September and October 1968, at the time that Trevor-Roper was writing his Philby Affair, a project undertaken at the instigation of Dick White. Harrison’s extract (on page 178 of Young Philby) includes the following text:

After Volkov’s kidnapping and the inexplicable delays and evasions of Philby’s visit to Istanbul, I became convinced that the warning given by Volkov of the presence of Soviet spies must be true, although I cannot claim to have recognised Philby as the principal culprit. I thought he was just irresponsible and incompetent . . . in the end I decided to give the story I outline to an American colleague . . .

Reed went on to say that the story, contrary to what Knightley claimed, was indeed sent up the line, and reinforced the doubts the Americans held about Philby when serious suspicions first arose. The added irony, of course, is that Menzies also believed that the warnings given by Volkov had merit. And Philby, in Trevor-Roper’s words, was ‘the most industrious and competent man in that generally lax organisation’.

Trevor-Roper did not use the anecdote from Reed, and compiled his short summary of the Volkov affair from the writings of the Sunday Times team, Page, Leitch and Knightley, concluding his chapter The New Machiavel as follows:

The memory of the mysterious Volkov affair then concentrated a suspicion which, otherwise, was diffuse: it formed the central and most persuasive change in the dossier which was now compiled, in M.I.5, for the interrogation of Philby.

When was that weaselly ‘now’? Trevor-Roper was unprofessionally vague. It was thus phrased to help Dick White and MI5 look sharp, of course. Indeed, some informal accounts I have received (from coldspur readers) reinforce the idea that other intelligence officers, such as Jane Archer, had their suspicions of Philby confirmed by the Volkov incidents. Maybe some currently unreleased files, or undiscovered memoirs, would tell us more.

Keith Jeffery’s Postscript:

I have remarked beforehand on Keith Jeffery’s studious ignoring of the Gouzenko and Volkov cases in his history of MI6, which was published in 2011. In a revised paperback edition issued in 2014, however, he added a Postscript that contained fresh material on both topics. It was if he had been stung into action when critics expressed their dismay that an authorized history, declaratively taking the story of MI6 up till 1949, had been so neglectful of the Volkov business, and Philby’s shameful betrayal of the service to the Soviets. Yet Jeffery introduces his material in a bizarre way. He first concedes that the story ‘has been told in outline’ by Christopher Andrew in his history of MI5, while his own Endnote vicariously lists The Storm Birds as a primary source. And then he writes:

No relevant documents have been found in the SIS archive, but newly unearthed Foreign Office papers now enable some telling details to be added to the narrative.

The thrust of Jeffery’s account is practically identical to Brook-Shepherd’s. So where did Jeffery imagine Brook-Shepherd had acquired his intelligence, if not from the same ‘Foreign Office papers’ that had clearly been ‘unearthed’ some twenty-five years beforehand? Moreover, Jeffery’s account refers to ‘a subsequent SIS report’, confirming that there were relevant pieces, even if this particular one had been stored in files of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. That passive voice again (‘no relevant documents have been found’): had Jeffery really been through the SIS archives himself, or had someone performed the task for him? It is quite astonishing how seasoned and respectable academics attempt to pull the wool over the eyes of their reading public.

A few differences can be detected in the two versions, however, mainly in dates and the format of names. Brook-Shepherd has Chantry Page, the vice-consul, receiving Volkov’s letter on August 27th : Jeffery indicates it was on the 24th. Brook-Shepherd represents the name of the counsellor who took charge as ‘Alexander Knox-Helm’: to Jeffery he is merely ‘a counsellor’ and appears as ‘Knox Helm’. Yet in his description of some of the incidents Brook-Shepherd offers more detail than does Jeffery: he identifies Cyril Machray as the (ignored) MI6 representative in Istanbul, and offers the startling information that John Bennett, an assistant press counsellor at the consulate, happened to be at the airport when Volkov and his wife (‘two limp and bandaged passengers’) were removed, heavily sedated. Bennett recognized, despite the bandages, that ‘the male stretcher case was Volkov’.

Of course it is difficult to determine whether Brook-Shepherd had access to files denied to Jeffery, or whether Jeffery simply was being more selective, but one might expect that the statement of Volkov’s sedated body’s being recognized should have been recorded by Jeffery as being of considerable interest. (Jeffery merely wrote that both Volkovs were ‘heavily sedated’ and that a subsequent SIS report logged their departure from Yesilkoy airport on September 26.) That identification would have told Menzies, Cadogan and co. that Volkov was certainly not a hoax. But why should we trust the anecdote from John Bennett?

The same year (2014), Ben Macintyre applied his energetic pen to the Philby’s career in A Spy Among Friends. He covers the Volkov business, but has clearly not seen the archival material, since he compiles his tale indiscriminately from the accounts of Philby, Knightley, Brook-Shepherd, Andrew – and Jeffery’s recent Postscript. His narrative is thus not very reliable (for instance, he places the events in 1944, not 1945), and his timeline is imprecise. He also informs us that the Volkovs, when abducted on to the Soviet plane, were ‘bandaged from head to foot’, which would presumably have made identification doubly difficult. Was that a creative flourish from Macintyre? In Deceiving the Deceivers (2004), S. J. Hamrick (who seemed not to have read Brook-Shepherd) referred to a ‘heavily bandaged’ Volkov. In Treason in the Blood (1994), Anthony-Cave-Brown, likewise not a student of Brook-Shepherd, described Volkov as being ‘unconscious and swaddled in bandages’. In The Young Kim Philby (2012), Edward Harrison (who lists The Storm Petrels but not The Storm Birds in his Bibliography) states that Volkov arrived at the airport ‘covered in bandages on a stretcher’. Trevor-Roper states merely that Volkov was ‘bundled, unconscious, on to a Russian plane’. Page, Leitch and Knightley describe the events as follows:

A Russian military aircraft made an unscheduled and quite irregular landing at Istanbul airport. While the control tower was still trying to think of something to do a car raced out to the plane. A heavily bandaged figure on a stretcher was lifted into the aircraft which immediately took off.

So where was Mrs Volkov? And how did Bennett get such a close-up view? Did he have his binoculars at hand? Could the NKGB really have been that clumsy, parading their victims in the airport’s concourse, or making such a melodramatic whistle-stop evacuation? Would an invasion of air space have been treated quite so casually by the Turkish government? On the other hand, Brook-Shepherd wrote that the military aircraft, arriving from Bulgaria, was nearly fired on by the Turks, but did not leave until the next day, and that Bennett was perspicacious enough to be able to detect that Volkov, though heavily sedated, was still alive. Where did these journalists get their information from? So many questions. I’d love to be able to read ‘that SIS report’.

The National Archives:

And then, in October 2015, maybe prompted by Jeffery’s undeniable access, a file on Volkov (FCO 158/193) was released to the National Archives. The historians and the public could inspect the text of Volkov’s original letter, as well as John Reed’s translation of it, and the careful analyst can make a better assessment of how its contents contributed to the deliberations of Philby, Wright, Brook-Shepherd and Jeffery. It is worth tabulating here, for posterity, what can be found in the file:

i) Carey Foster’s interest in the Volkov case, dated January 13, 1950.

ii) Stewart Menzies informing P. H. Bromley of MI6’s report on the case, dated October 19, 1945.

iii) ‘The Case of Constantin Volkoff’ (the report referred to by Menzies), undated.

iv) Copy of above, dated October 19, 1945.

v) Letter from R. G. Howe to A. K. Helm, carried by H.A.R. Philby, outlining procedures to be followed, dated September 24, 1945.

vi) Draft of above letter, with ‘Cadogan’ as author replaced by ‘Howe’.

vii) Copy of above letter.

viii) Letter from Bromley in Foreign Office to Menzies, enclosing Volkov papers, dated September 19, 1945.

ix) Minute from Howe to Cadogan, reporting on Volkov approach, dated September 19.

x) Letter from Helm to Codrington in Foreign Office, referring to Helm’s letter of September 5, and enclosing both Volkov’s letter and Reed’s translation of it, dated September 14.

xi) Reed’s translation of Volkov’s letter.

xii) A copy of Reed’s translation with handwritten comments.

xiii) A cipher telegram from Helm to Codrington that makes a disguised reference to a coming letter with ‘sales catalogue’, shortly to arrive in diplomatic bag, dated September 14.

xiv) Letter from Helm to Codrington, informing him of the ‘mare’s nest’ of Volkov’s initial letter and calling-card, dated September 5.

xv) Reed’s report on his interview with Volkov, dated September 4.

xvi) The note by SFH and Page that they decided to ignore Volkov’s initial letter, dated August 24.

xvii) Volkov’s initial letter, with attached calling-card, to Page, requesting meeting that day or the next, dated August 24. (This is almost certainly a translation: the original is not included.)

xviii) Reed’s original hand-written notes of his meeting with Volkov, dated September 4.

xix) Original hand-written note by SFH, dated August 24.

xx) Image of Page’s calling- card.

xxi) Volkov’s original letter in English (with spelling ‘Istunbul’), and photograph of Volkov’s calling-card, dated August 24.

xxii) A note stating that ‘the original papers in this file have been taken over from the Permanent Under Secretary’s file 1945 U.II U.S.S.R.’, undated.

xxiii) A letter from de Wesselow of MI5 to Street in the Foreign Office, returning with thanks the enclosed document, dated October 24, 1955.

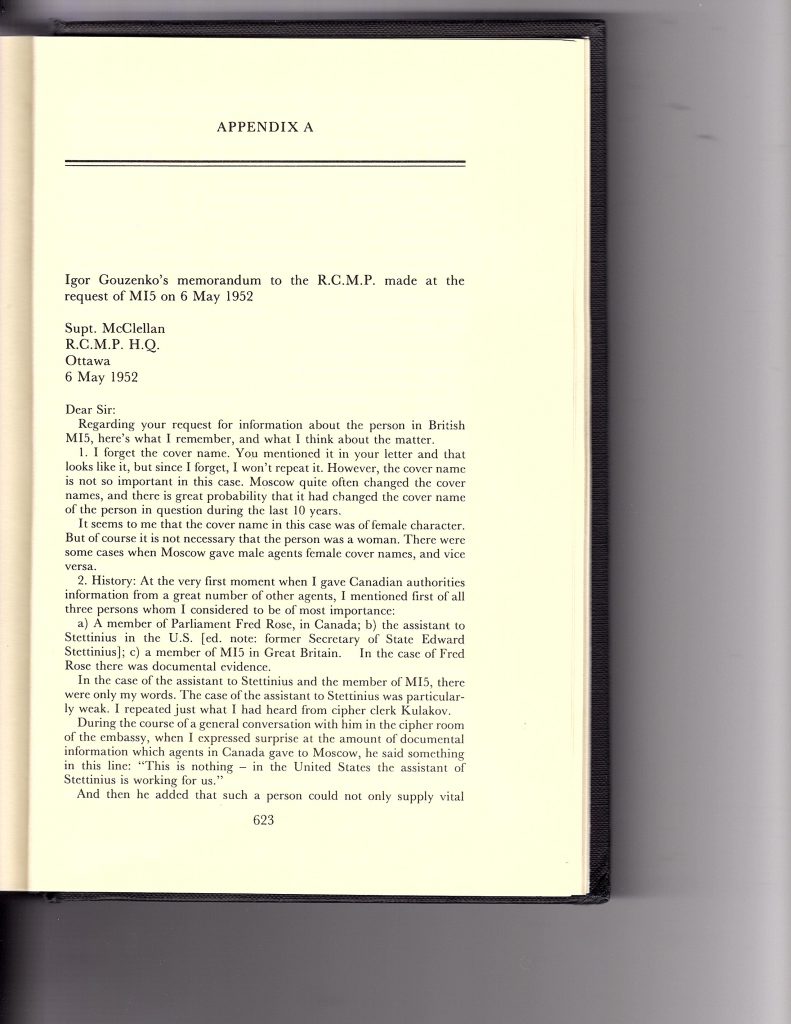

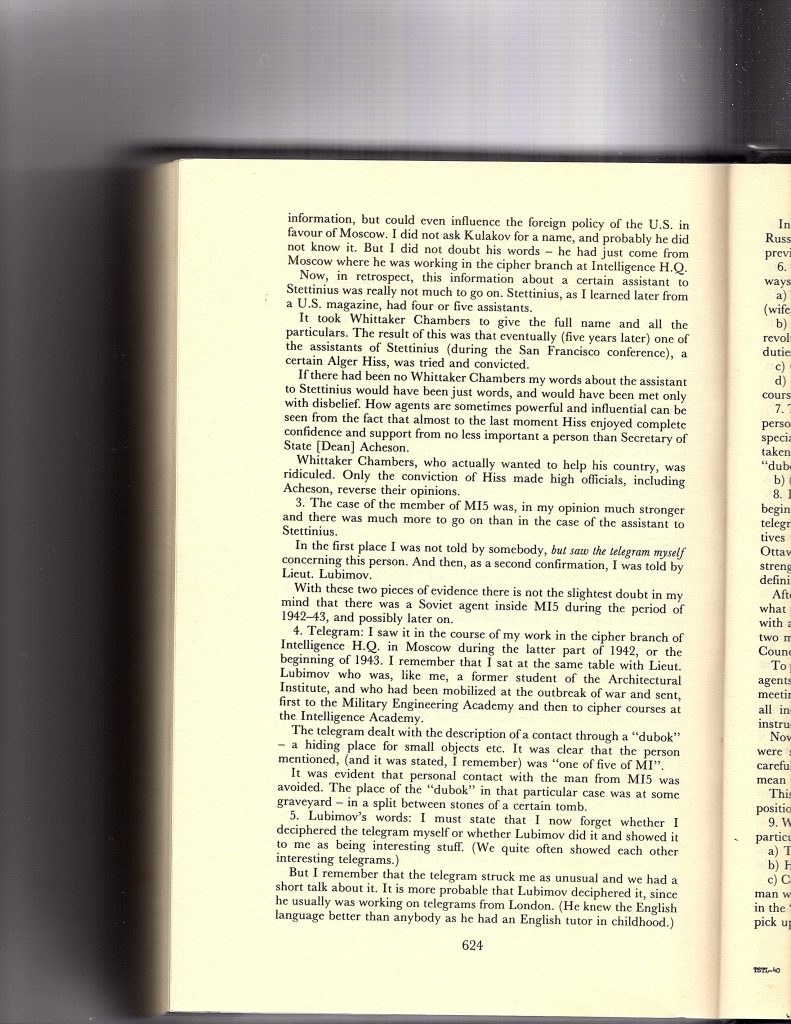

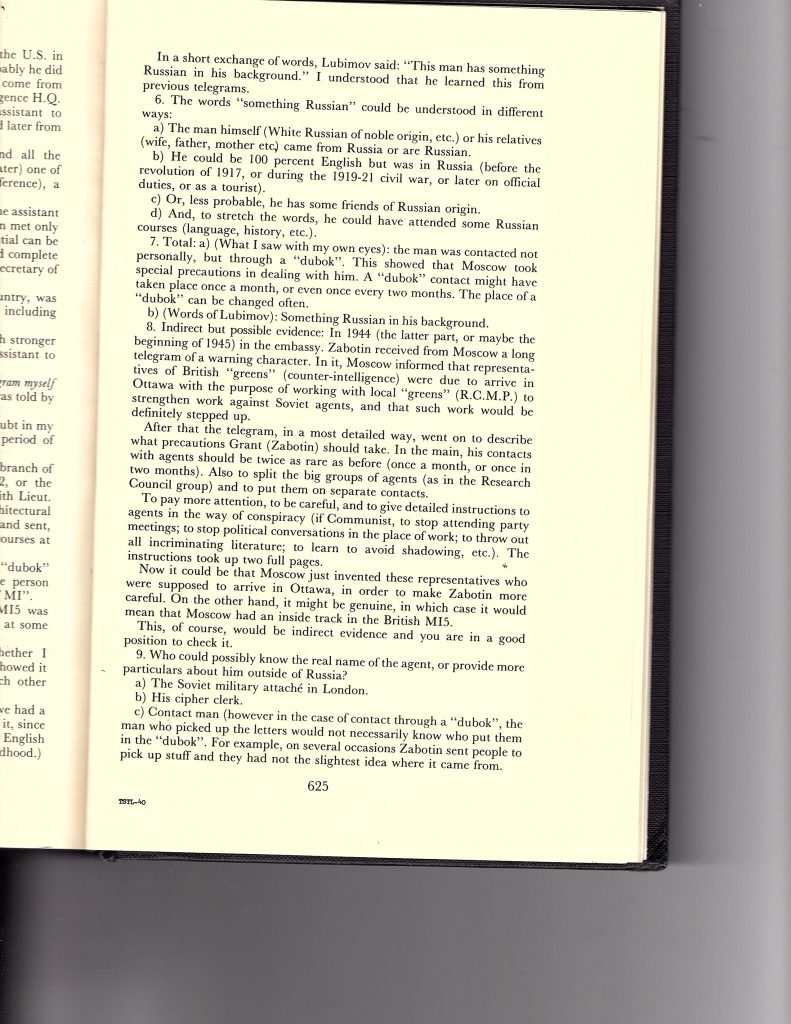

(xxiv) The Russian text of Volkov’s full statement, annotated as ‘originally retained by Security Service (P. M. Wright)’.

I offer a few observations on this file. The first very important conclusion is that its contents are not adequate enough to provide the intelligence that Brook-Shepherd and Jeffery derived. Yet it still fuels some insights that have not been made public, so far as I know. For instance, the letter in v) includes a last sentence added in manuscript, clearly inserted as an afterthought, that reads: “I would add that we have every confidence in Philby”. Why it should have been felt necessary to add such a comment about a senior MI6 officer is not clear: all it does is draw attention to the fact that others did perhaps not share that confidence. Did someone perhaps pipe up, and point out that Volkov’s description of a spy in counter-intelligence fitted Philby’s role quite precisely, with the result that his reliability had to be explicitly stated? Did Menzies ever pause for thought, when the translation of Volkov’s letter was brought to him on September 19, and wonder whether Philby should be kept off the case? Apparently not.

Some enciphered cables were obviously sent, despite the warnings that Volkov gave not to use them. Stewart Menzies reinforces this demand, and claims that it was honoured, in his report., although there is no indication that other routine cables not concerned with Volkov were suspended. (It night have been a considered a wise precaution, but, if all traffic suddenly stopped, that might have alerted any Soviet surveillance that something dubious was going on.) As another fascinating item, Menzies’ summary refers to ‘a detailed report received on October 3’ describing how Volkov and his wife had been removed at Yesilkoy airfield on September 26. That report is not on file, but its echoes meander throughout the literature on Volkov, as I have explained above.

And then there is the question of Volkov’s facility with the English language: the files state that he could not speak one word. Volkov specifically requested an English interpreter: Item 14 reveals the information that the official Russian interpreter at the Consulate was a Mr. Sudakov in the Passport Control Office (the cover for MI6).* It is not clear, however, who prepared Volkov’s original letter, as the presentation of it does not suggest that the document was a translation, and it has the city mis-spelled as ‘Istinbul’. Menzies’ report says that the letter, addressed to Page, was unsigned, but leaves the question of language unaddressed. Did Volkov receive help?

[* The name of ‘Sudakov’ is an intriguing one. In An SIS Officer in the Balkans (2020), John B. Sanderson and Myles Sanderson write that ‘The First Secretary of the Soviet Embassy in Ankara was a Brigadier General Sudin, in charge of “illegal residents” (spies), within Turkey, some of whom were Bulgarians. Penkovsky was a friend of Sudakov’s (Sudin’s alias) and would have passed over to his SIS handlers useful intelligence on Bulgarian espionage in Turkey, picked up in conversation with his high-ranking friend.’ More than fifteen years after the Volkov business, but just a coincidence?]

John Reed’s report of his meeting with Volkov on September 4 is also very provocative. He describes how Volkov arrived with the interpreter from the Passport Control Office, but the latter’s name is redacted. Since Reed’s Russian was, by his own estimation, ‘not very good’, he wanted to use the official interpreter, but Volkov (who spoke no English) insisted that they speak à deux, and the interpreter was dismissed. While Jeffery simply describes the interpreter as ‘locally employed, non-British’, without naming him, and implicitly casting doubts about his reliability, item xiv) explicitly names Sudakov as the PCO interpreter, and raises the question that Volkov may have been in contact with him beforehand. Volkov later spelled out that one of the agents he knew about worked in the British Consulate in Istanbul. If that person were Sudakov, it would not have needed Philby to alert the NKVD that Volkov was making clandestine approaches to the British Consulate. Reed also wrote that Volkov ‘had a great deal of information about the organisation of our secret service in this country and knew the names of most of our agents, Gibson, [XXXXXXX – redacted], Reed etc.’ While Reed protested vainly that he should not be on the list, the requirement for (presumably) Sudakov but not Gibson to be redacted is telling.

The most shocking feature, however, is probably the judgment of Stewart Menzies (item iii). Menzies assessed that Volkov was overall genuine, but that his intelligence was not uniformly reliable. For instance, he thought that Volkov’s figures on the numbers of agents were exaggerated, and he added an opinion about the cipher leak:

We tend strongly to the opinion that Volkoff was mistaken (possibly honestly) in asserting that N.K.G.B. cryptographers were reading Foreign Office and S.I.S. telegrams. On the other hand, information from other sources leads us to take seriously his statement that there are two K.G.B. agents in the Foreign Office and seven in the British “Intelligence Service”.

How Menzies was able to display this confidence is indeterminable. I note here that Reed’s memorandum of September 4 stated blandly that Volkov had said that Colonel Hill’s cables ‘were particularly easy to decipher’. Menzies must by this time have been advised of the George Graham fiasco: the Moscow-based officers Hill (SOE) and Barclay (MI6) were specifically identified by Volkov. Even if those breaches had not occurred, Menzies was far too complacent about the threat.

Menzies went on to blame Volkov’s own indiscretions for his betrayal, and then he showed a lack of resolve that undermined his previous statement about taking things seriously:

Finally, I would like to draw your attention to the fact that Volkoff’s information as to the existence of N.K.G.B. agents in official positions is so vague that it is improbable that we shall succeed in identifying them. To scrutinize the past records, and maintain observation, of all those who might possibly fill the bill would be impracticable as it would be invidious. While we, and no doubt M.I.5 as well, will do all that is possible in this respect, my own firm belief is that we shall achieve success only by offensive methods. It is in the U.S.S.R. itself, and in its diplomatic and commercial missions outside its boundaries, that the roots of this activity are to be found. If we want the information, we shall have to go and get it.

The intelligence he needed had been brought to his door by the very entity Menzies had identified as being useful. Apart from the fact that the pointer to Philby’s position could not have been more precise, the only reason that Volkov’s information was so vague was that his promised delivery of stronger intelligence pending negotiations had been dramatically shattered by Philby’s intervention. The head of MI6 was either very dim, or very scared – or possibly both. It was a scandalous admission of failure and incompetence: ‘we know we have Soviet spies in our midst, but we are not going to do anything about it’. Volkov had pointed to a spy working for MI6 in the legation in Istanbul, whither the staff had moved from Ankara: Menzies had Machray (the station-head), Gibson and Sudakov to investigate. Yes, certainly an investigation might be ‘invidious’, since innocent officers might have to be questioned, but that should have been the cost of doing business. It was no good pussy-footing around the whole problem, and doing nothing.

Jeffery surmises that Menzies’ report must have been influenced by Philby: ‘Menzies’s summary appears to have been drawn from the dismissive and disingenuous report which Philby claims he drafted on his way home from Istanbul’. This judgment is triply speculative, however, casting doubt on whether Philby ever compiled the report (it understandably has not surfaced), but then parading the knowledge that it was ‘dismissive and disingenuous’, and lastly making a guess at the circumstances behind Menzies’ compilation of The Case of Constantin Volkoff. It is true that Menzies reproduces such facts as the attempts to telephone Volkov after Philby’s arrival (which appear only in My Silent War, and not in FCO 158/193, so may well have been included in Philby’s report) but Menzies’ summary shows a familiarity with the dossier that does indicate that he had inspected the file himself. It would have been utterly irresponsible of Menzies to rely on Philby’s judgment exclusively, no matter how well he regarded him. Indeed, Brook-Shepherd had written that ‘Philby’s chief in London had immediately suspected some sort of leak the moment he learned that their quarry had disappeared, but the “solid evidence”, in the form of the hatchet men’s lightning mission from Moscow, was not then known.’ Unfortunately, as with many of Brook-Shepherd’s insights, the origin of this nugget is not declared.

It appears, however, that these source documents have not since been analyzed and attributed properly by any serious academics. For instance, Kevin P. Riehle’s scholarly and sober study of Soviet defectors, bearing that title (Soviet Defectors: Revelations of Renegade Intelligence Officers 1924-1945, published in 2020) cites Volkov’s claims, but uses as its source Brook-Shepherd’s book, not the archival material at Kew! Also in 2020, Professor William Hale of the School of African and Oriental Studies at the University of London wrote an article for The Journal of Anglo-Turkish Relations titled Espionage, Double-Dealing and Mystery: Kim Philby in Turkey 1945-1948, but, while making some useful observations on chronology, he does not appear to have studied the FCO files. (If anyone has come across any work that shows proper attention to FCO 158/193, please let me know.) The nearest attempt comes from Nigel West again, in his somewhat bizarre 2018 publication, Cold War Spymaster, purportedly about the legacy of Guy Liddell. (See https://coldspur.com/guy-liddell-a-re-assessment/ for my review of it.) West dedicates a chapter to Volkov, one that is fascinating and potentially extremely useful, but ultimately turns out to be confused and confusing.

Nigel West’s Cold War Spymaster:

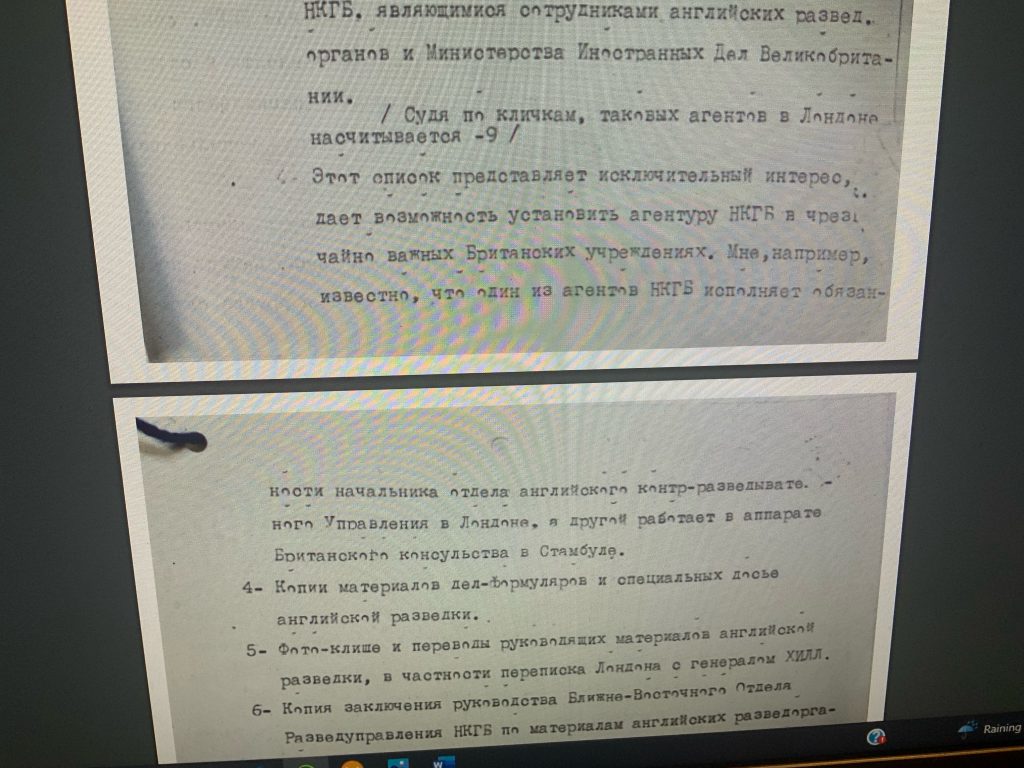

West actually reproduces photographs of both Volkov’s letter and Reed’s translation, which is an added bonus for those who cannot get to Kew. Yet the complete translation that he offers in his text is bizarrely not Reed’s (even though West introduces it as such), and it in fact corrects some of the blunders that Reed made in attempting to convert Volkov’s diplomatic jargon into relevant English. Astoundingly, West offers no explanation for this, and does not even explicitly name the translator. I wondered at first whether Geoffrey Elliott had been responsible, as I know he had performed translation work for West beforehand, but Elliott’s name is not listed, and I recall now that he had broken off all ties with West by this time. Yet a further search led me to discover that West had reproduced exactly the same text in his Historical Dictionary of Cold War Counterintelligence, published in 2007, where he coyly observed that ‘the actual text of Volkov’s letter remained classified for some time’. Such unnecessary fastidiousness and deceit: no doubt Brook-Shepherd shared it with him.

As an example of some necessary corrections that have been made, I refer to the Russian word ‘klichka’. Reed translates this as ‘cliché’ in one place, and ‘connection’ in another, and in both cases the sentences do not make sense. The word actually means ‘alias’ or ‘nickname’, and appears appropriately as ‘cryptonym’ in the published new translation. So perhaps there was merit in the case that Volkov’s text demanded a more strenuous attempt at translation? I shall return to that point later, but first need to inspect West’s account of the historiography.

The initial problem is that West inaccurately describes Volkov’s letter as it arrives on the desk of Sir Alexander Cadogan, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, with its passage about the nine agents in London, by quoting his new, anonymous translation. He cites the phrase about one of the agents who currently ‘fulfils the duties of the chief of an otdel (department) of the English counter-intelligence Directorate in London’, and adds that ‘another works in the apparat of British consulate in Istanbul’. Yet what Cadogan would have read, in Reed’s original text, was: “I know for instance that one of the agents of the N.K.G.B. is fulfilling the functions of the head of a Section of the British Counter-Espionage Service in London and that another is working within the British Consulate in Istanbul.” At first glance, this is not significant, but is there a difference between ‘Directorate’ and ‘Service’? Neither interpretation would appear to point unfailingly to MI5 or MI6. It is nevertheless a sloppy way of introducing the material.

West then switches to Guy Liddell’s diary entry of October 5, 1945, where the chief of MI5’s counter-espionage branch recorded the fact that the Volkov case had broken down (after Philby’s alerts to his masters, and Volkov’s quick removal to the Soviet Union and eventual murder). Here appears a very important entry, of which West reproduces only the last five lines::

The case of the renegade WOLKOFF in the Soviet Embassy in Istanbul has broken down. In accordance with instructions he was telephoned to at the Soviet consulate. The telephone was answered by the Russian Consul-General on the first occasion and on the second by a man speaking English claiming to be WOLKOFF but clearly was not. Finally, contact was made with the Russian telephone operator who said that WOLKOFF had left for Moscow. Subsequent enquiries showed that he and his wife left by plane for Russia on Sept. 26. Wolkoff had ovvered [sic: ‘offered’] to give a very considerable amount of information but much of it appeared to be in Moscow. WOLKOFF estimated that there were 9 agents in London of one of whom was said to be the ‘head of a section of the British counter-espionage service’. WOLKOFF said he could also produce a list of the known regular NKGB agents of the military and civil intelligence and of the sub-agents they employed. In the list are noted about 250 known or less well known agents of the above-mentioned services with details. Also available were copies of correspondence between London and General Hill of SOE in Moscow. WOLKOFF maintained that the Soviet authorities had been able to read all cipher messages between our F.O. and Embassy in Moscow and in addition to Hill’s messages [line redacted] the Russians had according to WOLKOFF two agents inside the F.O. and 7 inside the British Intelligence Service.

While this intelligence must have come as a ghastly confirmation to Liddell of the George Graham fiasco, it also indicates that Liddell picked up Reed’s account of the September 4 meeting that expressly stated that Volkov knew of two agents in the Foreign Office and seven working for Intelligence. Here also is the first confirmation of Volkov’s total number of nine agents – not seven, as Wright had claimed. (The Diaries were made available in 2002, and West published extracts in 2005.) Yet West immediately discredits Liddell’s testimony on two counts: the first, that Liddell had conflated the categories of ‘people known to the Soviets’ (i.e. fellow-travellers, agents of influence, etc.) with the numbers of those officially recruited by the NKVD (‘Soviet agents’), and the second, that he been creatively able to break down Volkov’s figure of nine agents. Instead of pointing out that Liddell’s total matched exactly what had appeared in Volkov’s letter, and that Liddell was merely citing what Reed had written, however, West immediately classifies this as an ‘error’, one that, according to him, would be perpetuated, and would ‘dog the intelligence community, and outside observers, for many years’.

It does not appear that West has studied FCO 158/193 carefully. Moreover, Liddell – in the full extract not reproduced by West – refers to additional details about the attempts to contact Volkov that do not appear in Menzies’ report in the file, but are indeed presented by Brook-Shepherd. This was in 1945, of course, so Liddell must have gathered those details from reading Philby’s report to Menzies, while Brook-Shepherd could have taken them from Philby’s memoir. West, however, moves swiftly on to drawing attention to Philby’s statement, which conflicts, but not in an absolutely contradictory way, with the Liddell/Volkov enumeration, and next introduces his readers to the significant figure of Gordon Brook-Shepherd, whose book The Storm Birds came out in 1989.

Having trashed Liddell’s breakdown, however, West now turns his querulousness towards Brook-Shepherd, accusing him of ‘distortion’ because not only had he misrepresented the figure of ‘250 agents in Britain’ (not a major issue, in my opinion), he had also redesignated ‘the nine agents in the Foreign Office or British Intelligence as two in the Foreign Office and seven in British Intelligence’. Yet the truth comes out: West concedes that Brook-Shepherd had been granted privileged access to some SIS files by the Foreign Secretary at the time, Douglas Hurd. So why was what Brook-Shepherd had written necessarily a distortion, especially if he was echoing exactly what Liddell had written forty-four years beforehand?

West then makes an awful meal of this observation, since he goes on to claim that Brook-Shepherd exerted an inappropriate influence on writers to come, with Christopher Andrew and Oleg Gordievsky being criticised for repeating it in KGB: The Inside Story (1990), and Andrew (again, this time with Vasili Mitrokhin) in The Mitrokhin Archive, in 1999. Lastly, in his history of MI5, The Defence of the Realm (2010), Andrew repeated what West saw as a ‘spurious figure’, West complaining that ‘apparently he had not looked at any original documents, nor gone beyond Brook-Shepherd’. Yet West himself does not explain the circumstances of Brook-Shepherd’s research, nor does he explain what ‘original documents’ could have been available at that time, apart from those passed furtively on to him.

Lastly Keith Jeffery, the authorized historian of MI6, gets the full West treatment. What is extraordinary is that West then lays out the work that went behind Jeffery’s addendum:

Professor Jeffery had the benefit of a trawl through the archives of both SIS and the Foreign Office which revealed the existence of a memorandum from John Reed, signalled straight to London and dated 4 September, to alert his superiors to the report to be entrusted to the diplomatic bag, and a summary, entitled The Case of Constantin Volkoff, dated around October 1945. In his account of the incident, Jeffery declares that in the absence of any surviving SIS documents, he had relied on previously unpublished internal Foreign Office correspondence; the Cyrillic original and the translation of Volkov’s letter; John Reed’s memorandum of 4 September and finally, the October summary which included a contribution from SIS.

In questioning Jeffery’s integrity, however, West ignores the fact that the materials in FCO 158/193, which he himself appears to rely on exclusively, might not represent the totality of the Volkov dossier. West gives no indication that he has seen these other papers, and for some reason treats them as inauthentic. One might wonder whether he has even inspected FCO 158/193, since he never gives it any attribution, either in his text or in his Endnotes, nor does he provide a source for the several pages of it that appears as plates in his book, which must have been derived from a bootleg edition, since the file was not released until 2015.

The most critical aspect of this mess, however, is the fact that a companion Volkov file to FCO 158/193 does indeed exist, namely FCO 158/194. On checking with the National Archives Directory, however, one learns that it has been ‘retained by the Foreign Office’. (see https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C14944128). I would be prepared to bet that that file contains the details that caught the attention of Liddell, Brook-Shepherd and Jeffery –, such as more information on Sudakov, a record of the attempts to contact Volkov after Philby arrived in Istanbul, the MI6 account of the Volkovs being removed at Istanbul airport, with Konstantin being recognized, and certainly Philby’s summarization of the affair for Menzies. There is probably a lot more besides, maybe even the names of certain agents.

The Volkov Text:

I find several aspects of Nigel West’s exegesis bewildering. The first is why the author would want to discredit the testimony of Liddell and Brook-Shepherd in an apparent attempt to give the Foreign Office, MI5 and MI6 an excuse. After all, if Liddell knew about Volkov’s references to two spies in the Foreign Office, even if he only confided it in his secret diary, then every senior official in Whitehall must have known about it as well, and should have made an attempt to link the dots from Krivitsky’s allegations to those of Volkov. When VENONA revealed the betrayals of Maclean, the profile of him and Burgess as the two Foreign Office spies should have been absolutely clear. On the other hand, the fact that seven spies were thus in the Intelligence Services (as opposed to the total of nine) did not materially affect anything. The hints should have been followed up within MI5 and MI6, but Liddell apparently did not initiate any project to try to identify those other agents within the Intelligence Services. Perhaps, fresh from the realization that Anthony Blunt and Leo Long had been caught red-handed the previous year handing over secrets to Britain’s war-time Communist ally (as I described in Misdefending the Realm), Liddell thought it was all rather harmless. His counterpart in MI6 Valentine Vivian obviously did hold that opinion, as I have also reported. Yet the knowledge that the perpetrators were not casual amateurs, but had deep connections and cryptonyms within the NKVD, should have rung loud alarm bells.

The second aspect is that Liddell, as chief of Counter-Espionage in MI5, having read Volkov’s text that described the head of a counter-intelligence department, and appropriately acknowledging that he was not the agent in question, should have been able, by a process of elimination, to home in on his opposite number in MI6 fairly quickly. Liddell’s suspicions about Philby, which were articulated to Eric Roberts in 1947 when the latter was considering a post in Vienna under the dubious Andrew King (see https://coldspur.com/a-thanksgiving-round-up/) must have been developed (or strengthened) at this time, but what is astonishing is the fact that Menzies quashed any attempt at an investigation, and the head of MI6 must have also been able to convince Sir Alexander Cadogan, who had been the first recipient of Volkov’s letter, that it was all disinformation, and a fuss about nothing.

A third dimension that strikes me as odd is the amount of emphasis that West gives to the accuracy of the enumeration of Soviet spies instead of paying attention to some of the other shocking revelations in Volkov’s letter. For instance, Item 5 in the letter states that the defector could deliver ‘Photostats and translations from English intelligence, in particular, London’s correspondence with General Hill’, and later, from a second offering, Volkov writes:

I can also give explanations about NKGB operations carried out against secret officials in Moscow (Hill, Barclay) and about sources of obtaining samples of English diplomatic and military ciphers in Moscow.

No comment is offered on these extraordinary disclosures. This is what Wright was referring to when he wrote that the Russians could read the Foreign Office ciphers, but the fact that this clue could have led to a case of human treachery, known by Boyle and Liddell, not mechanical interception, has been overlooked until now.

The last topic is the failure to examine the critical and controversial sentences of Volkov’s text, especially given what Wright claimed about its true meaning. My first transliteration of the key Russian phrases ran as follows:

Sudya no klichkam, takovikh agentov v Londone naschitivaetsya – 9.

Mne, naprimer, izvestno, chto odin iz agentov NKGB popolnyaet obyazannosti nachalnika otdela angliiskogo kontr-razvedivate, nogo Upravleniya v Londone, a drugoy rabotaet v apparate Britanskogo konsulstva v Stambule

I struggled with this task of transcription and translation. The word ‘razvedivate’ was puzzling, as the Russian word for ‘intelligence’ is normally ‘razvedka’ (and would require the genitive ‘razvedki’ in this context), while ‘razvedivata’ looks like a formation from the verb meaning ‘to reconnoitre’, obviously with the same root. One must also bear in mind that there are no definite or indefinite articles in Russian, so the interpretation of ‘a’ and ‘the’ can become problematic. Nor is there a present tense of the verb ‘to be’. The most mystifying word, however, was ‘nogo’, a form that I believe does not exist as a standalone word in Russian. (From Nigel West’s murky bootleg version, I wrongly read the word as ‘chevo’, ‘of which’; the official version is clearer, and unmistakably displays ‘nogo’. The genitive ‘ogo’ ending is actually pronounced ‘ovo’.)

And then the penny dropped. The key word was hyphenated across lines, and two letters had been lost in the photocopying. The complete word was ‘razvedivatelnogo’ (with a soft sign after the ‘l’): the word also appears in the first paragraph of Volkov’s letter, where he describes the corresponding Soviet unit.

I would thus translate these sentences as:

To judge by the cryptonyms, the number of such agents in London amounts to 9.

For example, I know that one of the NKGB agents carries out the functions of the head of a department of English counter-intelligence in London, while another works in the apparat of the British consulate in Istanbul.

Readers will note here some subtle changes from the earlier texts – both Reed’s and that of West’s unidentified translator. But is this information really expressed ambiguously? What the wording suggests to me is 1) that the first agent was temporarily fulfilling the role of a department head, and was not its formally appointed chief; 2) that the close proximity of the references to exurban offices and the consulate in Istanbul suggest that they both reported to the Directorate alluded to. How Volkov would have known the first fact is a mystery (and of course no date is given for the statement’s provenance), but why would he simply not write that the agent headed a department?

Yet, no matter how that interpretation is massaged, I do not see how a careful re-inspection of the text could contribute to the confident assertion that Volkov was pointing to MI5 rather than MI6. On the contrary, we should recall that, in 1943, Philby was deputy to Felix Cowgill, the chief of MI6’s counter-intelligence Section V. The unit operated out of St. Albans, outside London, and Philby stood in for Cowgill when the latter visited the United States. At this time, Philby’s Soviet handlers were pressing him to make a bid to take over the emergent Section IX counter-intelligence department. If anything, a close re-reading of the letter would reinforce the opinion that the references were indeed directed at Philby and MI6. Andrew draws the same conclusion, writing (p 517) that Philby was the most likely candidate, since he ‘had recently been acting head of SIS Section V (counter-intelligence), whereas Hollis had been the substantive (not acting) head of F Division in MI5 for five years.’ [The ‘five years’ is an overstatement, but the essence is true.]

And Occam’s Razor should be applied. Volkov was an NKGB officer. Philby was a proven penetration agent for the organization. Volkov would thus have known about Philby, and would have wanted to unmask him. Why would he obliquely refer to another reputed spy and not describe Philby’s role? It does not make sense. In The Philby Files, Genrikh Borovik plumped for Philby without question.

As a further commentary on Volkov’s intelligence, nowhere in the letter at FCO 158/193 does he indicate that he can ‘name names’ of the British agents in London. In fact his rather clumsy words indicated that what he can offer might help the task of identification, since his list of cryptonyms will ‘provide a possibility’ to ‘establish the agent network’ (‘ustanovyat agenturu’ – which Reed translated as ‘identify the agents’, and West’s anonymous translator, more literally as ‘establish the NKGB agents’). Thus it could be argued, according to the evidence of the quoted letter, that Wright’s claim that Volkov stated that he ‘could name spies in Britain’ was based on a mis-reading, or an erroneous recollection. Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, in Chapter 9 of The Mitrokhin Archive amplify this idea when they write, exploiting KGB files:

Under interrogation in Moscow before his execution, Volkov admitted that he had asked the British for political asylum and 50,000 pounds, and confessed that he had planned to reveal the names of no fewer than 314 Soviet agents.

But was that also based on a misunderstanding? The letter indicates that Volkov had access to several cryptonyms, but did not know many (if any) of the agents’ real names. Unless, of course, the alternative scenario holds sway. In that case, the interpretations of Philby, Wright and Brook-Shepherd, who all suggested London names were known, were indeed correct, since those three had inspected the putative unreleased – and more dangerous – documents that have presumably been withheld, in FCO 158/194.

In summary, this whole story displays some familiarly sad characteristics: the dishonourable behaviour of British officialdom, and its reaction to disquieting news; a lack of tenacity by the ‘doyens’ of intelligence historians in tackling the evidence. Revelations from a defector are not followed up properly. Attempts are made to bury embarrassing information, but it escapes anyway. Discriminatory and unlawful leaks are made in order to try to control the narrative, as an initiative of propaganda. The muddled speculations and analysis of a maverick and disgruntled intelligence officer are accepted far too credulously. Partial archival material is released, but other files are withheld without explanation. Facts, rumours and assertions become irretrievably mixed, as authorized historians cite dubious secondary sources, thus giving them undeserved credibility, and fail to apply proper historical methodology – a phenomenon that suits the bureaucrats, as it aids their goal of keeping the public confused.

2. Peter Wright and Double Agents:

Another of Wright’s quests was to determine why many of MI5’s operations running Soviet ‘double-agents’ had failed. He introduces the topic on p 175 of Spycatcher, where he writes, after describing how several microphoning operations had gone wrong:

Next I pulled out the files on each of the double-agent cases I had been involved with in the 1950s. There were more than twenty in all. Each one was worthless. Of course, our tradecraft and Watcher radios were mainly to blame, but the Tisler affair had left a nagging doubt in my mind.

[The Tisler affair referred to revelations from Frantisek Tisler, a cipher clerk in the Czech Embassy in Washington being run by the FBI. His friend Pribyl, when they were both in Prague on leave, had confided to him that he was running a spy in England named Linney. Tisler had to be protected.]