This month, I conclude my analysis of the accounts of Anthony Blunt’s Confession, and describe what I think really happened, and what the lessons are.

Primary Sources:

1 Defend the Realm [The Defence of the Realm in the UK] by Christopher Andrew (2009)

2 The Prime Minister’s Statement to the House of Commons: November 21, 1979 (extract)

3 The Fourth Man by Douglas Sutherland (1980)

4 Their Trade is Treachery by Chapman Pincher (1981: paperback version 1982)

5 MI5: British Security Service Operations 1909-1945 by Nigel West (1981)

6 MI5: 1945-72, A Matter of Trust by Nigel West (1982)

7 After Long Silence by Michael Straight (1983)

8 Too Secret Too Long by Chapman Pincher (1983)

9 Conspiracy of Silence by Barrie Penrose and Simon Freeman (1986)

10 Molehunt: Searching for Soviet Spies in MI5 by Nigel West (1987)

11 Spycatcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer by Peter Wright (1987)

12 Mask of Treachery by John Costello (1988)

13 Seven Spies Who Changed the World by Nigel West (1991)

14 My 5 Cambridge Friends by Yuri Modin (1994)

15 The Perfect English Spy by Tom Bower (1995)

16 The Enigma Spy by John Cairncross (1995)

17 Anthony Blunt: his lives by Miranda Carter (2001)

18 Open Secret by Stella Rimington (2001)

19 Last of the Cold War Spies by Roland Perry (2005)

20 Triplex by Nigel West (2009)

21 CIA files on Straight (released March 2007)

22 The FBI Vault: Michael Straight

23 Treachery by Chapman Pincher (2012)

24 The Shadow Man by Geoff Andrews (2015)

25 FCO 158/129 – ‘Foreign and Colonial Office file on John Cairncross, 1953-1982’ (released 23 October, 2015)

26 Spymaster by Martin Pearce (2016)

27 CAB 301/270 – ‘John Cairncross, former member of the Foreign Office: confession to spying’ (released July 20, 2017)

28 Enemies Within by Richard Davenport-Hines (2018)

29 The Last Cambridge Spy by Chris Smith (2019)

30 Agent Moliere by Geoff Andrews (2020)

Secondary Sources:

The Historian as Detective: Essays on Evidence, edited by Robin W. Winks (1969)

With My Little Eye by Richard Deacon (1982)

The Secrets of the Service by Anthony Glees (1987)

The Haunted Wood by Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev (1999)

The Art of Betrayal by Gordon Corera (2012)

The Secret World by Hugh Trevor-Roper (2014)

Historical Dictionary of British Intelligence by Nigel West (2014)

The Black Door by Richard J. Aldrich & Rory Cormac (2016)

A Question of Retribution? edited by David Cannadine (2020)

How Spies Think by David Omand (2020)

MI5, the Cold War and the Rule of Law by K. D. Ewing, Joan Mahoney and Andrew Moretta (2020)

I see four major topics encapsulating the study of the Hoax of the Blunt Confession: the circumstances of the encounter itself at the Courtauld Institute; the contribution made by Michael Straight; the details of Cairncross’s confession in Ohio; and the role and character of Arthur Martin. All these issues are coloured by the actions and objectives of Roger Hollis and Dick White.

The Events at the Courtauld Institute:

It must be borne in mind that all reports of the circumstances of Anthony Blunt’s confession derive from one source – Arthur Martin, who apparently carried out the project singlehandedly. The unnumbered and unidentifiable archival record that Christopher Andrew claimed to have seen must have been written by him. Martin was the source for the accounts adumbrated by Chapman Pincher, Nigel West, and Barrie Penrose and Simon Freeman, even though some of them they may have been channelled through Martin’s fellow officer, Peter Wright. All subsequent narratives rely on one or more of these five authors. Thus the analyst has to deal with the disquieting fact that Martin disseminated conflicting accounts of what happened, and I shall inspect later to what degree I think this aberration was due to artifice or to indiscipline.

To begin with, the encounter’s externalities clash. In the official record, Martin called on Blunt on the evening of April 23, as if on an unscheduled visit, in the hope of finding his quarry at home (1). Alternatively, it occurred in the mid-morning of April 22 (10), or perhaps in the morning of the following day (12). By all accounts, Martin carried out the interview alone (a fact which American intelligence officers found astounding (12)), although a report in the Washington Post of November 22, 1979 quoted Sir Michael Havers, the Attorney General, as informing the House of Commons that ‘When officials [sic] went to Blunt’s Home in April 1964 to question him for the 12th time . . .they revealed new information implicating him’. The report in Hansard simply states that Blunt was interviewed ‘by the Security Service’.

Thereafter, the accounts diverge further. The authorised version runs as follows (1): Martin asked Blunt about Michael Straight, at which Blunt started to twitch. He disagreed over Martin’s account of Straight’s recruitment, at which point Martin offered the assurance of immunity should Blunt confess. A minute of silence followed, before Martin informed Blunt that he had recently put John Cairncross through such an exercise, and gained a confession. Blunt declared that he needed ‘five minutes to wrestle with his conscience’. He then left the room for five minutes, returning to pour himself a drink. He stood at a tall window for several minutes. Martin appealed to him again, whereupon Blunt came back to his chair and confessed.

Several aspects of this account are highly unlikely – or pure melodrama. The fact that Blunt apparently expressed no shock or surprise on learning of Cairncoss’s confession, and asked no questions about it, suggests that the claim was a later insertion to the archival record (as I have earlier suggested), or that Blunt already knew about the events in Cleveland, but fluffed his lines. Instead, he is reported to have made the ludicrous remark about his ‘conscience’ – an item in the screenplay that Alan Bennett would not have considered including even on an off day. To give the game away about having a guilty conscience before making the confession would have been an astonishing mis-step by someone who had successfully weathered almost a dozen interrogations beforehand. And what was the evidence from Straight that incriminated Blunt? That Blunt had tried to recruit him in Cambridge twenty-seven years ago, maybe acting on behalf of Guy Burgess? After all, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher had said in 1979 that Blunt had come under suspicion ‘as a result of information to the effect that Burgess had been heard in 1937 to say that he was working for a secret branch of the Comintern and that Blunt was one of his sources’. The whole scenario seems like a bad comic opera.

One might also question the wisdom of a single junior officer’s being charged with such an assignment, especially since Blunt was allowed to leave the room for several minutes. Would he come back? Might he have done a runner, or even topped himself? Was a posse of Special Branch constables waiting outside to apprehend him should Plan B have been required, in the event that a saloon from the Soviet Embassy rolled up to steal him away? One cannot imagine the KGB goons indulging Oleg Penkovsky or Oleg Gordievsky with permission to leave the room for a few minutes while either gathered his thoughts. (‘Certainly, comrade. But don’t be too long, mind.’) Pincher very early on thought the whole performance was bogus (8), that Blunt had been pre-warned, and no plans had been made for the eventuality where he did not confess. Martin echoed this opinion to Costello (12): he may have thought that he was breaking fresh ground in having been granted the peachy assignment, and executing it so successfully, but the way that it developed make him think otherwise, and no doubt contributed to his frustrations.

Yet the evidence that Martin provided to other journalists added further wrinkles. In his first testimony to Pincher (4), Martin offered differing evidence (without mentioning Cairncross), describing a scenario where Blunt never left the room. According to Nigel West (6), Blunt took only a few seconds to confess. In Pincher’s next offering (8), he also echoed the point that Blunt capitulated too soon, and that Martin never articulated the conditions of the immunity deal. Moreover, Pincher introduced the fact of the tape-recorder as a substitute for any written record. One might think that Blunt would have reacted to such an obvious device with some alarm or mis-giving, but nothing appeared to faze him. He agreed to the recording, knowing that it would have no legal status. Penrose and Freeman (9) even state that Blunt ‘nodded in assent’ when the tape-recorder was presented.

The evidence of these latter two authors was dependent upon letters that Martin had conveniently supplied to them in 1985. In this deposition, Martin said he had ‘unequivocal evidence that Blunt had been a Soviet agent during the war’: the authors state that Blunt denied this, ‘as the assertion simply wasn’t true’. It is not clear whether they are expressing their own opinion, or Martin’s, but the fact is that the assertion was true (the business with Leo Long in MI14), but had been conveniently been buried. If Martin truly did have access to this information at the time, it could have appeared to him as more damning evidence than the stories Straight old, but White and Hollis had known about it, and tried to minimise its significance. No conceivable new source of this allegation is given, but perhaps Martin had been given this ammunition just beforehand. Since that gambit provoked no response, Martin next turned to his interviews with Straight, but Blunt was ‘expressionless’ (no ‘twitching’ then), walked to the window, poured himself a large drink (without leaving the room), and immediately admitted to Martin that it was all true. In this version, Martin played back the recording, so that Blunt could agree that it was an accurate record of the conversation. (How could it have been otherwise?) The meeting was over after twenty-five minutes.

According to West (10) and Wright (11), the events were collapsed to a shorter time-frame, with Wright indicating that Blunt admitted his espionage ‘almost immediately’. While gin has been shown to be the preferred tipple up till now (4), Miranda Carter suggests that Blunt ‘poured himself a large Scotch’ (17). In his last work on the subject (23), Chapman Pincher picked up from Penrose and Freeman the thread of Blunt’s wartime complicity and detection, but did not investigate the source of this new intelligence. He echoed the story that Martin had told Costello that Roger Hollis had warned Blunt about the coming confrontation.

The whole charade is a mess. Amid all these conflicting stories, however, one thread appears prominent: that Michael Straight had provided breakthrough evidence of Blunt’s guilt. And it was that external evidence, rather than MI5’s mismanagement of its suspicions, that had given the senior officers of the Security Service an alibi, and had provoked Blunt’s confession.

Michael Straight & Anthony Blunt:

Michael Straight was a somewhat sad actor in this whole pantomime. His life and career were characterized by irresolution, privilege and lack of purpose. He was pliable and weak. Critics of his memoir have challenged him as to why he did not confront his own missteps earlier, instead of conniving at the activities of his erstwhile Cambridge colleagues in espionage. He vacillated, admitting his failings, but was also deceptive and misleading in his explanations. A review by a CIA officer of his memoir concluded: “As to Michael Straight himself, no semantic contrivances can avoid the conclusion to which he guides us; as both man and agent he was too gullible, too idealistic, too self-serving, and too long silent.”

For example, when Straight made his long-winded confession to the FBI in June 1963, he emphasised his contacts and friendships in Cambridge, and admitted his recruitment by Blunt, but minimised the level of espionage he had undertaken, and understated Blunt’s close association with Moscow (see below). He claimed tentatively that, during his assignments with his contact Michael Green (Akhmerov) in Washington, ‘he may have furnished Green with memoranda which he prepared from public material and his personal knowledge’. When Pincher broke the story of the investigations into Hollis in Too Secret Too Long in 1983, and pointed indirectly to Straight, Straight claimed to David Binder of the New York Times that he had declined Blunt’s 1937 invitation to spy. (Pincher may well have alerted the journalist. The column about Straight’s denial appears on the same page of the March 26, 1981 issue as the news on Hollis.) In After Long Silence, Straight admitted that he had ‘failed to reject Anthony’s scheme out of hand’, but again claimed that he had passed on to Akhmerov only papers he had written himself, or publicly available material.

Yet, reluctant spy that he claimed to have been, Straight was indeed persuaded to hand over important classified material. In The Haunted Wood (1999), Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev, the latter having inspected relevant KGB archives, record the usefulness of agent NIGEL (Straight’s cryptonym). They write, for example, “Nevertheless, in June [1938], he finally delivered his armaments report to Akhmerov, and, the following month, the Russian noted that Straight had passed on a report from the American consul in London about British war reserves of raw materials.” While Straight’s contributions waned after the announcement of the Nazi-Soviet pact, his Moscow bosses still considered him an important ‘agent in place’, and obviously had a hold over him by then. The US authorities would surely have not have been as indulgent with Straight after his confession had they known the true extent of his treachery.

Commentators have asked: ‘What took him so long to confess?’ And ‘Why did he confess so much?’ After all, was it really necessary to introduce Blunt as his recruiter, given that all his espionage was carried out in the USA? Yet Straight was aware that his Communist affiliations in Cambridge were known by a few, and probably believed that, if he did not tell a comprehensive story, and then further unpalatable facts emerged, he would face fresh challenges. By 1963, however, the McCarthyite climate of the early nineteen-fifties had ameliorated, and previous communist sympathies would not have been so harshly treated. That does, however, provoke, a further question that I do not believe has been analysed: ‘Did Straight warn Blunt of his proposed confession?’ And if so, ‘how and when?’

Since there was a sort of childlike simplicity and decency in Straight, I believe that he would not have betrayed Blunt’s role without informing him of his intentions, and I thus suspect that the two of the must have prepared the ground before June 1963. They surely met some time after that as well, before the improbably late and apparently harmonious encounter in September 1964 that Straight describes in his memoir (7), on an occasion which is strongly referred to in the CIA and FBI records (21 & 22), and implied, with supporting evidence, by Perry (19). Moreover, we have the perplexing series of events described by Costello (12). Costello also believed that Blunt would have been given a warning, but presented messy evidence from various items of Courtauld correspondence. Lastly, we have Costello’s suggestion that Blunt made a late decision to travel to Pennsylvania for his summer lecture series (12), when published evidence confirms that the commitment with Blunt had been forged a year earlier.

The timing of Straight’s confession, as articulated by the agent himself, is driven by his coming nomination to the Advisory Council on the Arts, and set in June 1963. But it is quite probable that he had considered such eventualities earlier than that. In his memoir, he tells how he had completed two novels in 1962, was looking for other ‘good causes’ to pursue, and that his mother-in-law had been trying to secure him a prominent position several times before he was approached about the position of Chairman of the Fine Arts Commission in May 1963. With his interests (he had been editor of the New Republic from 1948 to 1956, and on the board since), he would surely have heard about Blunt’s public invitation by the University of Pennsylvania, and Perry records his visit to the United Kingdom in April, where he stayed at Dartington Hall in Devon (‘his third trip inside a year’) and then spent time at 42 Upper Brook Street in London, ‘a short walk from Blunt’s flat in Portman Square’. Straight did not disclose this visit in his memoir: he conceded to Costello that he had been in the UK that April, but claimed that he had not visited the Courtauld.

If Straight was reconciled to making a (partial) confession at this time in the confidence that he would emerge without penalty, Blunt may also have felt emboldened. Philby had absconded to the Soviet Union from Beirut in January of that year, and Blunt had made a provocative and controversial visit to that city the month before. On November 18, 2013, the BBC posted a bulletin by George Carey (https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-24803131), who pointed out that Blunt had gone to Beirut in December 1962, staying with his friend the British Ambassador (Sir Moore Crosthwaite), on a quest to find a frog orchid. But frog orchids apparently do not grow in the Lebanon, so Carey assumed that Blunt was lying. The conventional interpretation of this visit is that Blunt came to warn Philby about the imminent arrival of MI6 officer Nicholas Elliott, sent to unmask him at last, and that Blunt had been sent by his Soviet controllers.

Blunt had previously visited Philby there, some time in 1961. In Their Trade Is Treachery (p 142), Chapman Pincher relates how Blunt later admitted to helping Philby escape, describing how he had visited Philby in his flat, in an event that is undated. His host had said: “I have been asked by our friends to make contact with you, Anthony, but I have told them that you are not in a position to do anything useful”, an opinion to which Blunt gave his immediate assent. Yet this encounter seems incongruous to me. If Blunt took advantage of his presence in Beirut to look up Philby, why would Philby show the initiative by saying that their ‘friends’ (Moscow) wanted to re-establish contact with Blunt? Would that not have been simpler for the KGB to do in London, without drawing attention to an unusual rendezvous in Beirut? And, if Blunt had not been in contact with his KGB masters for a long time, while Philby apparently still was, how come that Blunt had been sent by them to warn Philby, when they could have relayed a message to Philby through their own networks? Moreover, 1961 would have been very early for aiding Philby in his escape plan, unless Blunt was conflating two visits into one.

It is thus plausible that Dick White, continuing to use Blunt as a ‘consultant’, knowing him to be tainted, but believing him to be far less dangerous than Burgess, Maclean and Philby, sent Blunt out to alert Philby of Elliott’s impending arrival. White knew that the best place for Philby was Moscow, rather than being repatriated for an embarrassing trial. After all, how would Blunt have learned of this highly secret mission? That would explain how Philby was prepared for Elliott’s visit, as he explained when he told his former fellow-officer that he had been ‘expecting him’ (10).

Be that as it may, and given that the evidence, like all other material in this investigation, is largely circumstantial, Blunt did not appear unduly embarrassed by Straight’s actions if he knew of them in the summer of 1963. The garbled statements from Mrs Jefferies about Blunt’s chagrin that Straight was ‘going to shop them’ are impossible to analyse properly unless the original letters surface (12). For instance, why is the letter dated August 1962? Moreover, it seems highly unlikely, to me, that Straight would have been allowed to visit the UK so soon after his interrogation, in July 1963, before the FBI and MI5 had discussed the case properly. After all, Sullivan asked him only that month whether he would be prepared to repeat his story to British intelligence! And it also seems very improbable that Blunt would be able to make a decision to fulfil his commitments for a summer school in the USA as late as that, and then depart for a six-weeks adventure. (Of course, if all these events at the Courtauld did occur in 1962, it would bring an entirely new perspective to the discussion.)

Lastly, some commentators have pointed to Blunt’s probable irritation at the continuing deceit and subterfuge, and his fear that Guy Burgess might return to the United Kingdom and unmask him. Andrew Boyle raised this question in The Climate of Treason, suggesting that Blunt wanted to get his story out first, and control the narrative. Yet Burgess died on August 19, while Blunt was in the USA. Yuri Modin suggested that he confessed as a reaction to Burgess’s death (14), a counter-intuitive idea if one accepts the previous premise. In his review of The Climate of Treason in the Spectator on November 17, 1979, Hugh Trevor-Roper echoed this notion, since Burgess in Moscow had threatened to expose him, which, in the historian’s words, ’would have been fatal for Blunt’. Trevor-Roper overlooked the fact, however, that, if Burgess had successfully negotiated a guarantee of immunity, it would have had to be applied to Blunt (and others) as well, in the fashion that Blunt’s eventual deal was extended. Trevor-Roper then made the rather illogical statement that Blunt’s confession ‘may have been unnecessary, since Burgess then died in Moscow, having revealed nothing.’. Either the writer was pointing to an earlier confession (something clearly not indicated by the rest of his text), or he was confused by the chronology. It is all very strange.

The FBI & MI5:

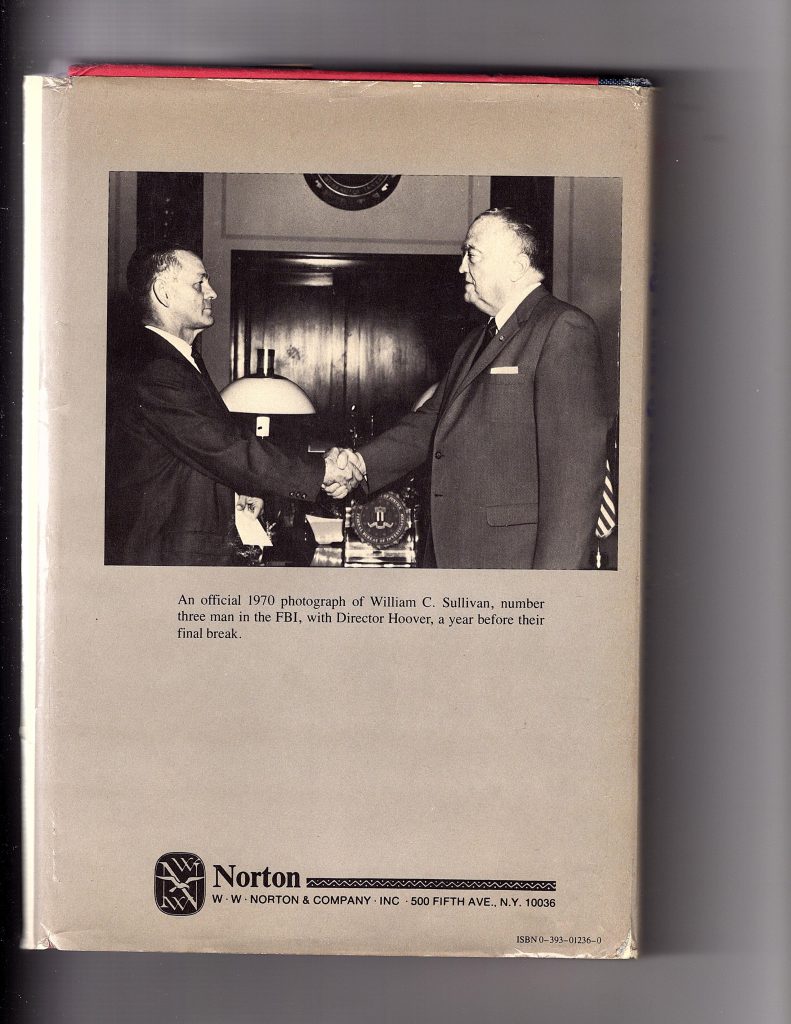

Thus it seems more fruitful to start by inspecting the intentions of the FBI to inform their colleagues in MI5 of what had transpired with Straight. The assertions of a delay until January 1964 are made by Nigel West (6 & 7), on the grounds that Hoover did not trust MI5 with the material. He again attributes the lack of action to ‘petty inter-agency rivalry’ (13), presumably suggesting competition between the FBI and the CIA, though why that should be, given the clear territorial responsibilities, is not clear. Admittedly, J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI’s chief, never told the CIA anything. Carter (17) says that the FBI waited several months before telling Martin. To select Martin as their target would have been highly irregular, as it would have bypassed the proper level of communication. Even if Hoover and Sullivan had trusted Martin more than they trusted Hollis, it would have been a crass political move.

Yet the FBI and MI5 appeared overall to enjoy a positive relationship. Roger Hollis went back with Hoover a long way. As the Liddell Diaries inform us, in the summer of 1945, Hoover had made repeated requests to MI5 Director-General Petrie for Hollis to visit the FBI to help them with plans for countering Soviet espionage. In 1950, during the Pontecorvo investigations, Hollis had felt impelled, when head of F Division, to tell George Strauss, the Ministry of Supply of the ‘special relationship’ between the two organisations. As Edward Perrin reported on November 9: “Roger Hollis of M.I.5 was present at the meeting with our Minister last Monday and he made it very clear that the utmost care should be taken to avoid release of this information [concerning BSC, RCMP, and US Embassy in London], particularly in view of a recent agreement reached between Sir Percy Sillitoe and Mr. Edgar Hoover of the F.B.I. to the effect that neither organisation would say anything about the other’s actions without consultation and agreement.” (FO 371/8437) (In the light of the Fuchs and Pontecorvo fiascos, Hoover may have been assuaged by the fact that he had just been awarded an honorary KBE.) And Richard Deacon, in his 1982 memoir With My Little Eye, wrote (p 226) that Hollis ‘had been on exceptionally good terms with the allegedly anti-British J. Edgar Hoover to be given a signed photograph and a set of golf clubs.’ Strangely, Andrew offers no analysis of the relationship between the FBI and MI5 between 1950 and 1963. Liddell refers frequently to Hoover’s temper, but it seems that the FBI director was much more concerned about his personal reputation and status than he was about relations with MI5.

There appear to be no available archival records of any early communications on the Straight business from the FBI to MI5. Andrew states, however, that Hollis flew out to Washington at the end of September, having been encouraged to do so by the Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan (1). Hollis had been barraged by a cabal of MI5 officers (Wright, Martin, Winterborn, and one other), who each threatened to resign unless MI5 were open with the FBI about the Mitchell investigation – a worrisome lack of group judgment, as it turned out. Wright claimed in Spycatcher that Hollis faced opposition from his officers when he was more cautious about revealing MI5’s embarrassing inquiries to the Americans (11): it is not clear whether Andrew extracted this fact from Wright’s book, or had access to an alternative source, so readers should be naturally cautious. In any case, Hollis had been unnerved enough to have to consult with White over the visit, and then gain the approval of the Prime Minister. Since Macmillan had been required to inform President Kennedy of the possible exposure caused by the suspicions over Mitchell, and had been ‘humiliated’ by the experience, he was anxious that no more secrets be withheld from the Americans, and gave the nod.

For some reason, Martin followed a day later, to go into the details of which American intelligence sources might have been compromised (1). Yet, if Hollis did glower across the table at Martin, and say he would brief the Americans himself, he might have decided to do so in order to request of his counterparts that the rewards from the Straight confession not be shared with Martin when he followed. As West claimed, Hoover’s deputy, Sullivan, had been ordered not to reveal Straight’s existence (20). And, if Martin did indeed fly over the following day, Hollis could hardly have succeeded in convincing his team that he perform the briefing exclusively himself, since he was not familiar enough with the details.

Another version of the story has Dick White playing a more active, almost interfering, role. In this scenario (15), White recommends that Hollis inform the FBI and the CIA about the state of the Mitchell inquiry, at which Hollis ‘reluctantly’ flew out. If this is true, it shows that Hollis was even more under the influence of White, taking instructions from him on how to handle the situation. Hollis certainly would have bridled at revealing what had occurred to the arch-molehunter James Angleton of the CIA, but, since the latter would otherwise have been informed by Maurice Oldfield, White’s man in Washington, it was something he had to swallow.

In any case, it would seem hard to imagine that the meetings in late September would not have presented the perfect opportunity for Hoover and Hollis to discuss the Straight confessions. And, when he returned to the UK, Hollis surely shared what he learned with White, but probably with none of his subordinates in MI5 – certainly not with Martin. That is what Pincher surmised (8). The intelligence from Straight provided Hollis and White with a perfect opportunity to inform their political masters that proof of Blunt’s guilt had come from an outside source, thus distracting attention from their own fumblings. The two of them may then have decided that a further session with Blunt was called for, and prepared to invite Straight to come over to confront him.

That would explain the suggestion that Straight was in London in the October-November period (19), and what Straight himself admitted to the CIA (21), where he actually stated that he had a private fifteen-minute meeting with Blunt before the MI5 officers entered the fray. This visit was confirmed by what Straight ‘later’ told the FBI about confronting Blunt in London, claiming that his challenges to Blunt ‘broke’ him and made him admit his espionage (22). Pincher refers to a letter concerning Straight sent to the US Embassy in November (8), but does not present the details. It may have referred to Straight’s coming visit. Of course, the ‘confrontation’ may have been a staged act by the pair of them, but the event surely occurred. Straight may have lied to the FBI about the nature and extent of his own espionage, but it is hard to imagine why he should have deceived them over the external circumstances of this encounter.

As for the secrecy within MI5, Pincher wrote that Martin ‘was not informed about Straight in the November time-frame’ (8), which represents a very strong indication that an important meeting did occur then, but that events were not explained to Martin until some time in 1964, when Martin’s career crisis occurred. (Pincher declares that, at the time, in January 1964, Martin believed that the Washington encounter was the first occasion where MI5 had heard about Straight and his information.) The source for this assertion is, tantalisingly ‘the Straight-Martin correspondence’. * Obviously, if Martin had been told about the November agreement at the time, he would not have been interested in listening to Straight in Washington in January. Correspondingly, Straight must have been sworn to an oath of secrecy about his visit to London: otherwise, he would have briefed Martin about it in Washington. It seems highly likely that Martin and Straight exchanged letters after April 1964, and Martin thereby learned the whole story. Pincher also makes the strange claim that Straight ‘was ignored by MI5 during the November visit’ (8), but that can be interpreted as the fact that he was overlooked by the rank and file because they were not aware of his presence in London.

[* In Too Secret Too Long (p 360), Pincher refers to ‘Correspondence Between Straight and Martin in 1982’, but his note suggests that Straight corresponded with Pincher in 1982, referring to earlier letters exchanged with Martin. These letters have not been located, so far as I know.]

The conclusion must be that the immunity agreement with Blunt was made at the end of 1963. The primary source evidence is scarce, admittedly, but no scarcer than that supporting the April 1964 confrontation, and the secondary indications are stronger and more consistent. Blunt presumably successfully sought immunity as well for Leo Long and John Cairncross (at least), who were the leading lights that he identified to his interrogators. Hollis and White were surely the only intelligence officers who knew about it, and Hollis hoped to keep it that way. Whether Dick White had any ulterior motives must be an issue for debate. Yet the situation was thrown into rapid turmoil through the fortuitous but unfortunate entry of Cairncross himself into the drama.

Cairncross and His Visa:

John Cairncross’s appearance in London, probably in December 1963, can only be an extraordinary coincidence. The existence of the Graham Greene-Cairncross correspondence proves that Cairncross had approached the author as early as August 4, 1963 for a reference for the position at the Western Reserve University (30), so it is impossible that MI5 could have lured him from Karachi to be interrogated in London as a result of Straight’s involvement. Thus Cairncross’s appearance there, before travelling to Rome to pick up his paperwork, must have caused much embarrassment. First of all, Blunt had very recently named him as a fellow-conspirator, a fact that MI5 would have to address. Secondly, Cairncross had applied to the USA authorities for a visa. If MI5 concealed from US Customs and Immigration (via the FBI) what they had learned from Blunt, it would no doubt turn out to be a frightful indictment when the FBI found out about it later. If MI5 informed the FBI, Cairncross’s visa would surely be denied, and the publicity risk of preventing an apparently harmless citizen from pursuing his career would have to be faced. In fact, even without the recent unveiling of Cairncross, if he had been honest in any interviews he had with the US immigration authorities, his previous political sympathies should have excluded him, as the Foreign Office files suggest (25).

All this leads to explain the extraordinary shenanigans that were displayed by Cabinet Secretary Burke Trend and his colleagues (27). MI5 wanted the job appointment to go ahead, and to pursue the serious interrogation of Cairncross on foreign soil, where any testimony would have less standing. Thus they had to ‘fix’ the FBI. If we are to believe Pincher (23), Martin flew out to Washington in early January, presumably to explain the dilemma, and to convince the FBI to go along – at least temporarily – with the plan to indulge Cairncross. The Foreign Office files prove that Cairncross had applied for the visa some time before February 7, 1964, albeit with a degree of urgency. Martin must have performed his task effectively, because a later memo confirms that his visa had been granted (25).

Thus the conflict over Martin’s presence in Washington appeared to be quickly resolved. It was not as a follow-up to the ‘Mitchell inquiries’, as Pincher was led to believe early in the cycle (8). The need to talk to the FBI about Mitchell had evaporated, and nothing of that nature would have required such an extended stay. (Pincher’s claim that Hollis deputed the task of interviewing Straight to Martin, and then recalled him before the interview (8) is patently absurd.) It did not arise as a result of Martin’s accepting a long-standing invitation by Sullivan to talk to Straight (7). West asserts that Sullivan had been ordered by Hoover to be very discreet about Straight, and not reveal what had occurred (20). It is impossible to imagine that Martin would have been given permission by Hollis to visit Washington on such a pretext, and again, such a project would not have taken weeks. Martin had been sent to handhold the FBI through the Cairncross project.

Martin was in ignorance about the recent Blunt confession. As laid out above, Martin told Pincher that he did not know about the ‘November confession’ (8). He was assuredly also not told about the Cairncross interview that must have occurred, where Cairncross was instructed in the role he had to play. And then, when he arrived in Washington, Martin was told by Sullivan that he needed to meet an important person. This is the encounter that Straight describes in his memoir, expressing surprise that he had not been called ‘before January 1964’ (7). Where they met is a matter of dispute, though probably immaterial. Straight’s Daily Telegraph obituary says Martin ‘attended a lunch given by the FBI’s Bill Sullivan, where he met Straight, who volunteered to confront Blunt’. Nigel West has told me that Penrose and Freeman were wrong in indicating that the meeting took place at the Mayflower Hotel, and that the lunch was held at Straight’s club in Washington.

What is more important is why the encounter was arranged. One can believe that the molehunters in the CIA – enthusiastically led by Angleton – would by now have become extremely frustrated by the lack of follow-up on MI5’s part after Straight’s unmasking of Blunt. The meeting was surely set up without Hoover’s knowledge, and I have pointed out that Sullivan had been forbidden to mention his name to any MI5 officer. That, in itself, must have bred resentment. Martin had been working closely with Angleton ever since the arrival of the defector Golitsyn, and Martin disclosed that he had had to be discreet about Straight because Sullivan had been ordered not to reveal his existence (20). What is potentially ominous, however, is the possible involvement of Maurice Oldfield. In the memoir of his uncle, Martin Pearce makes the claim that Sullivan liaised with his ‘MI6 associate’, Oldfield, and that Oldfield ‘arranged for Arthur Martin to fly out to interview Straight’. This is a provocative statement, as the official lines of communication were MI6-CIA and MI5-FBI, and the FBI and the CIA were jealous enemies. Yet Martin had gained the confidence of Angleton, showing that the contacts were by now more flexible. I have not been able to gain a confirmation of this item from Pearce, but, for the multiple reasons given above, it sounds totally implausible that Dick White, notwithstanding his influence over Hollis, would have been able to arrange for Martin to fly out on such a mission.

Martin was no doubt astonished and energised about Straight’s revelations, thinking he had fallen on a scoop. Yet he did not immediately return home in excitement, contrary to what Penrose & Freeman, Bower and Perry all asserted (9, 15 & 19). Nor did he meet Straight after his interrogations of Cairncross, as West claims in his books on MI5 and in Molehunt (5, 6 & 10). Pincher distorts the events utterly (8 & 23). Whether Martin subdued his excitement until he returned home, or whether he sent a cable to alert his bosses, cannot be determined. If Sullivan warned him appropriately, he probably kept it to himself until his return. For Martin was to stay out in the United States for several weeks, as the Cabinet papers prove (27).

Finally, an analysis of Straight’s evidence is in order. Martin was impressed enough by what Straight told him to believe that it was the information that MI5 needed to nail Blunt. He was ‘elated’ (7). But what did Straight tell him? If he repeated to Martin what he had told the FBI, as he claimed, his account did not point to espionage on Blunt’s part, but to his role as a messenger. It referred to ‘anti-fascism’, ‘the Third International’, to an opinion that Straight was required to gather economic data in New York, that Straight’s ‘protests had been rejected’, and that Blunt was a ‘mild communist’, and was acting on behalf of Burgess (22). Yet in his memoir, Straight clearly indicates whence Blunt was getting his instructions, as the latter refers to the fact that Straight’s reluctance had been discussed in ’the highest circles of the Kremlin’.

Reliable information indicates that MI5 already knew that Blunt was not just an ‘intellectual communist’, and had direct links to Moscow. Professor Glees wrote an article for the Journal of Intelligence and National Security in 1992 (Volume 7, Number 3), titled War Crimes: The Security and Intelligence Dimension, resulting from an assignment with the British Government. In this piece, Glees wrote that, in 1952 (the Sillitoe era), MI5 had discovered from an Eastern European ex-Soviet intelligence officer that an ‘art adviser of HM the King worked for Soviet intelligence’. This is, to me, an astonishing revelation, indicating a far more serious indictment of Blunt than a casual supplier of military secrets to a wartime ally, which is how White and Hollis probably viewed him at that time. Even if, again, the evidence would not stand up in court, the direct identification would surely have been something that Blunt would have struggled to deny. Glees stated that this item would have been presented ‘to the very highest level in the Security Service’. * Assuredly so, and Martin, and the other officers who repeatedly interrogated Blunt, were not made aware of it.

[ * The information did not apparently reach Guy Liddell, deputy Director-General in 1952. His Diaries show that he continued to seek Blunt’s advice over problematic communists in the summer of 1952, and even came to the spy’s defence when he was warned – probably by Goronwy Rees – about Blunt’s shady past. Did Sillitoe pass on the information to White on the latter’s accession in 1953? I imagine so.]

The Cairncross Confession:

The confession all happened very quickly. Andrews suggests that Cairncross had been ‘pleasantly surprised’ that MI5 had done nothing to stop his visa application, and confidently travelled to London to perform research at the British Museum and see his estranged wife, Gabi (30). Yet it was a while before the application was approved. In a rather breathless minute, Street in the Foreign Office reported, on February 18, that not only had Cairncross’s application been approved at last, but the subject had also already confessed! Cairncross had flown to New York on February 11, and had been notified by a Customs official that he would be needed for further questioning when he reached his destination. Martin had visited him at his hotel in Cleveland on Sunday, February 16, and apparently gained a confession immediately. The haste and efficiency of the whole operation were almost unseemly, and certainly suspicious.

Why had Cairncross confessed so rapidly? The explanations are hardly convincing. Cairncross’s own story is unreliable, primarily because he sets the event as occurring in April (16), presumably to grant the timing rather more credulity. In his version, an FBI officer arrives first, informing him that Arthur Martin will be calling shortly. When the MI5 officer declares that he believes that Cairncross has not told the whole story, Cairncross folds, out of a desire to ‘make an end to this cat and mouse game once and for all’. He guesses that someone has informed on him, and concludes that it must have been Blunt, a notion espoused by Costello (12), thereby giving ammunition to the theory that Blunt confessed first, as Geoff Andrews boldly indicates (24). West has a slightly different representation: the meeting was ’by appointment’, and Cairncross ‘attended’ because he was fearful about his job (20). That goes against the grain of Smith’s account, which states that Cairncross was ‘doorstepped’ (29), suggesting an element of surprise.

But what would one expect the normal reaction of a person in Cairncross’s position to be, as an innocent academic who has just been cleared for employment in the United States? He is warned at US Customs, but seems to express no alarm. When Martin and the FBI turn up, he does not reflect: why on earth did these people allow me to come all this way, and then immediately harass me about these long-ago events? When Martin approaches him with the soft-ball challenge that he may not have told him all before, why does he not send him away with a flea in his ear, and tell him he has nothing more to say? It must have been because he was primed for the whole episode before he left London, and it was explained to him that Blunt had confessed, and that he likewise would be given immunity from prosecution if he admitted everything on foreign soil.

So all the references to ‘a second bite of the cherry’ – after twelve years (10), ‘D Branch retracing its steps’ (7), and Cairncross’s being ’thrown to the wolves’ by Blunt (29), must be discarded. So must any assertion that Cairncross received no immunity, and thus risked returning to London at his peril (30), although.in his book on Klugmann (24), Andrews singularly does state that Martin offered Cairncross an immunity deal. Claiming that Klugmann had been his recruiter, and thus distancing himself from Blunt, was part of that agreement. Now Hollis and Trend have to go through the machinations from the Cabinet Office (27), trying to establish what the FBI and the US Immigration Authorities will do, hoping to avoid publicity, and attempting to ensure that Cairncross finds a safe haven in a foreign country (Italy) where he will not be able to cause any trouble. And the FBI duly expels him in June – not to Cairncross’s obvious surprise, it seems.

As I have shown, Martin did not rush back after this interview. He had to stay while the panjandrums discussed what had happened, and decided what to do next (27). On February 19, Trend informed the Prime Minister of the confession. Douglas-Home convened a meeting, at which it was determined that gaining a statement under caution should be attempted. On March 2, Martin was thus instructed to return to Cleveland, and the news quickly came back (on March 4) that Cairncross had declined the invitation. So, probably in mid-March, Martin was able to return to London, and brief Hollis and White on the Straight breakthrough. According to Bower, White, in true Captain Louis Renault style, was ‘shaken’ by the news (15).

Hollis must have been furious, however. First of all, how and why could Sullivan of the FBI break the commitment that Hoover had given him about keeping the Straight business confidential? And why had Martin been snooping around in Washington, communicating with CIA people without instructions to do so, when he had been sent specifically to liaise with the FBI on Cairncross? Moreover, on his return Martin must have pressed for interrogation of Blunt, and prosecution. He was probably told that the evidence that Straight provided would not stand up in court, and that Blunt would continue to deny everything. Fresh from his triumph in Cleveland, however, Martin probably believed he was on firm ground. Even though Hollis was infuriated by Martin, he was probably encouraged by White to appease him, and that is where the rumour started that it was Martin’s idea that Blunt should be offered immunity (despite Martin’s lack of sympathy for the idea), and that Martin would be chosen to interview Blunt in his flat (4). And that is what led to the pantomime of late April, where the key players (except for Martin) repeated their roles from the previous November.

The Role of Arthur Martin:

Arthur Martin remains an enigmatic figure. Why was such an ordinary but volatile officer selected for such an important task? How much did he know? Why had he become such an enthusiastic acolyte of James Angleton? Why did Dick White recruit him after Hollis had suspended him? And, most intriguing of all, why did he spread such conflicting stories about the Blunt confession?

(A profile of him can be found at https://spartacus-educational.com/SSmartin.htm, but it contains several egregious errors, primarily on chronology.)

Martin had his champions. Michael Straight found him ‘sophisticated and urbane’, in contrast to FBI agents (7), and told the CIA that he was ‘the original for George Smiley’ (21) – an unconvincing comparison. According to William Tyrer (who accessed the Cram archive), Cleveland Cram, CIA officer and historian of the agency, may have been echoing what Straight told him when he observed that Martin was ‘generally agreed to have been the counterintelligence genius of the British services’, surely an over-the-top assessment. Penrose and Freeman, while characterising him as ‘unprepossessing, self-made, and down-to-earth’ (does the suggestion of plain speaking jibe with ‘sophistication and urbanity’?), went on similarly to portray him as ‘a creation of John le Carré; a brooding spycatcher’ (9). Furthermore, they wrote: “His mind was a constant blur of bluffs and double-bluffs and, although he never claimed to be an intellectual, he was quick-witted and open-minded.” (Martin may have helped promote that image himself.)

In his Guardian obituary, Richard Norton-Taylor referred to Martin’s ‘sharp, analytical mind’ (but that could surely be said of most intelligence officers worth their salt), and in his BBC piece, described him as ‘a hardened interrogator’. Cairncrosss described him as ‘one of the most effective intelligence officers I have ever met’ (16), yet, since Cairncross probably met few such animals, and doubtless wanted to provide a solid explanation as to why he had quickly confessed, he probably over-egged the pudding. And Nigel West offered Martin praise for his performance at the Courtauld, writing of ‘the carrot dangled skilfully’, which appears a bit of a travesty when the record is inspected carefully. Peter Wright claimed that Martin proved himself ‘a brilliant and intuitive case officer’ (11).

Yet Martin had his critics and detractors, too. His close associate, Peter Wright, was also one of the most outspoken, writing that he was ‘temperamental and obsessive’, and ‘never understood the extent to which he had made enemies over the years.’ Bower expressed some surprise at White’s ‘tolerance’ for Martin (15). White was told that Martin ‘had a chip on his shoulder’, a judgment echoed by Gordon Corera, but then White was overall too trusting of people until it was too late. Christopher Andrew depicted Martin as follows: ‘a skilful and persistent counter-espionage investigator . . . , but he lacked the capacity for balanced judgement and a grasp of the broader context.’ (1) Andrew also considered him and Wright ‘the most damaging conspiracy theorists’, one of the most damning dispensations the historian can deliver (see https://www.mi5.gov.uk/mi5-in-world-war-ii ), and this characterisation was echoed by John Marriott of MI5, who wrote in an earlier memorandum: “In spite of his undeniable critical and analytical gifts and powers of lucid expression on paper, I must confess that I am not convinced that he is not a rather small minded man, and I doubt he will much increase in stature as he grows older.” (1; 28)

Martin had worked for the Radio Security Service (RSS) in World War II, and then moved to GCHQ, where he was liaison officer to MI5. Andrew informs us that it was Kim Philby who recommended him to MI5 in 1946, having met him in his RSS days. (Martin was apparently disappointed to have been replaced by Elliott for the mission to Beirut to interrogate Philby, though why an MI5 officer would have been considered for the job is not clear. Gordon Corera claims that White believed that Philby would be more likely to confess to an old friend.) Martin’s Guardian obituary stated that he was the first to learn – from the CIA – that Klaus Fuchs was a Soviet agent. Yet this would appear to contain some grandstanding. Serial 260/9 in KV 6/134 shows that Maurice Oldfield communicated the breakthrough news to Martin on August 17, 1949, and that it resulted from the efforts of Dwyer and Paterson (the MI6 and MI5 representatives in Washington), working on research performed by Philp Howse of GCHQ. Thus the first symptoms of Martin’s vainglory appear. In his Historical Dictionary of British Intelligence, Nigel West reinforces Martin’s contributions, but it is hard to identify any specific counterespionage feat he accomplished, apart from those placed in his hands by such as VENONA and the disclosures of defectors.

It was Martin’s encounter with the defector Golitsyn that set him on the trail of believing that the British intelligence services were infested with moles, and I turn the reader to Chapter 10 in Section D of Andrew’s Defend the Realm to learn more about his dogged efforts, and the obstacles and objections he faced in his pursuit of traitors (although the details of some events, such as the transfer of Cumming, and the reorganisation of D Division, are wrong). In the episodes when first Graham Mitchell, and then Roger Hollis, were suspected of being Soviet agents, Martin gained an inappropriately sympathetic ear from Dick White, who had been his mentor when Martin acted as White’s emissary in 1951. Then Martin had helped to plant hints on the CIA that Philby was the primary candidate for abetting the escape of Burgess and Maclean (see DickWhite’sDevilishPlot.) White, of course, had been a senior officer in MI5 at the time, and shifting the blame to MI6 helped him protect his position and career. In 1963 and 1964, from his vantagepoint as chief of MI6, White was now quite happy to suggest that MI5 was the leaky vessel, in order to achieve a similar goal.

Thus Martin was an unlikely choice to carry out a careful interrogation of Blunt. It was not that he had similar successes under his belt, unlike the experienced (but overrated) Jim Skardon, for instance. His noted successes with the Portland Spy Ring and Vassall cases were prompted by information from defectors rather than superlative sleuthing. Gordon Corera credits him with his persistence in trying to pin down Philby’s guilt, and convincing Dick White of the fact, but White himself had understood that back in 1951. The exercise was probably set up as a sop to his vanity: having believed that he was going to impress Hollis and White with his news from Straight, he was rebuffed by their lack of enthusiasm. Hollis and White had their hands forced, but would later be able to represent the faux confession as something imposed on to them by Straight’s revelations, when in fact they knew about the facts all along. They needed to try to keep Martin loyal. Martin had not been told of the November-December 1963 negotiations with Blunt (as his comments to Pincher indicate (8)), or the details of the Cairncross interviews in London, but he must have been informed of the requirements of the Cairncross case, as he was sent on a delicate mission to strategise with the FBI some weeks before Cairncross’s arrival in the United States.

And then he got into trouble with Hollis, becoming such a disruptive influence, frustrated that Blunt was continuing unpunished, demoralised that Cumming was moved into the D Division as his boss, and next having key personnel removed, that he had be suspended, and then dismissed. Corera writes: “Even his friends acknowledged that he lacked tact, but he became increasingly reckless, even self-destructive, in his single-minded pursuit.” (The Art of Betrayal, p 204) Yet for White to then hire him, in November 1964, was very controversial. As Aldrich and Cormac write in The Black Door (p 241): “Remarkably, Dick White, who had been director-general of MI5 and was now chief of MI6, was inclined to agree with Martin, and felt that suspicions lingered around his former colleagues Hollis and his deputy, Graham Mitchell.” The whole episode is redolent of what happened to Jane Sissmore, when Guy Liddell had to fire her in 1940 under dubious pretexts, whereupon she was picked up by MI6. White’s action was a monstrous insult to his protégé Hollis.

Lastly, what could Martin’s motivations have been, in adopting such a scattershot approach to leaking information to journalists and writers? Was he undertaking an official disinformation exercise? And, if so, was he simply chaotic and disorganised, with a faulty memory? I think not. In his 2020 poorly titled but overall engrossing study of how intelligence analysts should approach their tasks, How Spies Think, David Omand, former head of GCHQ, explains what is essential to detect a successful disinformation project. “The corollary is that to detect deception as many different channels should be examined as possible. It requires great skill to make the messages consistent on each channel and avoid errors. One inconsistency may be enough to reveal the deception.” (p 267) Thus, if an agency is going to peddle a Big Lie on any target audience, it has to have a watertight, well-conceived story – such as the legends developed by the Double Cross team in World War II.

Yet Martin’s (and Wright’s) stories are all over the place, riddled with inconsistences, conflicting chronologies and details, and unconvincing psychological portraits. I have come to the conclusion that Martin probably did this deliberately – to draw attention to the fact that a gross injustice had been performed, and a cover-up perpetrated, and to provide solid hints for the more intrepid and inquisitive of those who chronicled the events that the story was not as it seemed. Andrew Boyle got a portion of the way there, but the baton was scandalously dropped by every analyst afterwards. And one of his stories even reached the authorised history, thus receiving officially blessing.

Martin retired from MI5 in 1969, and took on a job as a clerk at the House of Commons. In 1984, he collaborated with Stephen de Mowbray in writing an Editor’s Foreword for their ghosting of Golitsyn’s New Lies for Old. He died in 1996, after expressing public doubts that Hollis had been a spy. As Anthony Glees records in the Secrets of the Service (p 316), Martin had written in the Times, on July 19, 1984, that only new evidence could shed light on an inconclusive case. His second marriage was to Guy Liddell’s secretary, Joan. According to West, both he and his wife ‘abhorred’ the notoriety that his doggedness over KGB penetration had brought him.

Summary:

Here follows my version of events.

Sometime in 1963, probably in April, Michael Straight and Anthony Blunt agreed to try to regularise relations with their respective intelligence authorities. In June, Straight confessed to the FBI, and the news was passed on to Roger Hollis, who kept it to himself and Dick White. In September, Hollis in person impressed upon Hoover the need for secrecy. Straight was invited over to the UK in October, where he briefed Hollis and White, and a highly confidential immunity agreement for Blunt was made with the help of Cabinet Secretary Trend, Home Secretary Brooke, and Attorney General Hobson. Blunt revealed the involvement in espionage of (at least) Cairncross and Long, and pointed the finger at several other dubious characters. Cairncross unexpectedly sprang on the scene in December, when he arrived in London in the process of trying to gain a USA visa to work in Ohio. MI5 convened a hurried session with Cairncross, where they explained to him the situation, promised him immunity if he would talk, and explained that they would prefer to interrogate him formally in Cleveland. MI5 started negotiations with the FBI for the approval of Cairncross’s visa.

Martin was sent on to Washington in advance, to finalise the visa arrangements, prepare the ground for Cairncross’s interrogation, and to alert the FBI of the sensitivity of the situation. With Oldfield’s assistance, Martin was immediately introduced to Straight, as Angleton and the CIA had grown impatient with the lack of evident action on the interrogation of Blunt. Cairncross arrived in the USA in February, and swiftly confessed, but Martin had to stay on to try to gain a statement from him under caution, which Cairncross not surprisingly declined. Martin returned to London, armed with the new evidence and expecting a hero’s welcome, but was chagrined at the lack of enthusiasm for interrogating Blunt. Hollis and White then decided to re-stage the confession, with Blunt’s obvious compliance. But Blunt remained not only unprosecuted but unscathed. Martin quickly realised that he had been hoodwinked, and started to make boisterous objections, which eventually cost him his job. He landed on his feet under Dick White in MI6, but the resentment lingered, and White became an enthusiastic supporter of his theories about a mole in MI5.

Conclusions:

I present five main areas of conclusion, on the essence of the hoax, on the policy of offering immunity, on Hollis’s lack of leadership, on White’s duplicity, and on the failures of authorised history.

The Hoax:

Some might argue that this was no hoax, since no obvious victim was deceived. Perhaps the events were just part and parcel of the cloak-and-dagger activities that are intrinsic to the business of the ‘Secret World’. Yet a large deception was undertaken. And why did MI5 plant a bogus document in the archives, unless they intended seriously to mislead someone? The authorized historian was deceived, swallowed the whole story, and everyone who followed him trusted what appeared in Defend the Realm.

In a partial sense, Blunt’s confession was a hoax. He committed to give a full confession, but prevaricated and dissembled, so that his interrogators never gained the full story. But the major hoax was that perpetrated by Hollis and White, in the deceptions they played against various agencies. They claimed to the Home Secretary and the Attorney General that that it was Straight’s testimony that proved Blunt’s guilt, when they already had powerful evidence of his traitorous activities that they had kept to themselves. They concealed from their own officers in MI5 the fact that a very private deal with Blunt had been concluded in December 1963. They prepared documentation for posterity that indicated that an authentic confession had been elicited from Blunt in April 1964, when the whole episode had been choreographed. In addition, in a supplementary plot where they tripped over themselves in the chronology, they suggested to the Foreign Office that Cairncross had confessed for the first time, in Cleveland, in February 1964, when they had in fact followed up Blunt’s revelations the previous December and interrogated Cairncross in London.

In The Historian as Detective: Essays on Evidence, edited by Robin W. Winks (1969), Jacques Barzun and Henry F. Graff made an important distinction between the genuine and the authentic. They wrote: “The two adjectives may seem synonymous but they are not: that is genuine which is not forged; and that is authentic which truthfully reports on its ostensible subject.”. In this scheme, the Hitler Diaries would be ungenuine and inauthentic, a counterfeit copy of a book would be ungenuine but authentic, and Arthur Martin’s description of the Blunt Confession would be genuine but inauthentic. It is that document – if it exists – that is the kernel of the hoax.

The Failure of Immunity:

Offering immunity from prosecution in exchange for full cooperation is not a strategy.

This policy might be called the Macmillan Doctrine, since the Prime Minister, when admonishing Roger Hollis for proudly informing him that MI5 had caught the spy John Vassall, declared: “When my gamekeeper shoots a fox, he doesn’t go and hang it up outside the Master of Foxhounds’ drawing room; he buries it out of sight”. Yet Macmillan overlooked the fact that, while dead foxes may tell no tales, pardoned spies usually have witnesses, who will frequently seek that fairness and equity be observed. As Ewing, Mahoney and Moretta remind us in their recent book on MI5, MI5, the Cold War and the Rule of Law, in 1961 Macmillan pressed for immunity to be granted to George Blake, in exchange for his full co-operation, but Dick White insisted that the business go to trial. Blake was sentenced to forty-two years, and the later comparison of the fate of Blake (a Dutchman with a Jewish father) with that of the aristocratic Blunt helped fan the flames of the protestors’ cause.

The problem is that the authorities will never know how much co-operation they are getting from their suspect. In his August 7, 2020 Times Literary Supplement review of A Question of Attribution (the British Academy and the Matter of Anthony Blunt), edited by David Cannadine, Richard Davenport-Hines wrote: “The compact between the Security Service and Blunt was broken by a novice prime minister fifteen years later.” Yet that is a perversely one-sided interpretation of what happened: the news had escaped through no fault of Margaret Thatcher, but Blunt remained unprosecuted. Blunt did not fulfil his side of the bargain, as his wishy-washy written ‘confession’ shows. Moreover, one condition of Blunt’s immunity deal, insisted upon by the Attorney General, John Hobson, was that he admit that he had not spied after 1945, as Miranda Carter reported (17). So what did Blunt do? He made that assertion to Martin, one which turned out to be untrue.

That does not necessarily mean that Blunt should have been prosecuted. A public trial – or even one held in camera – would have been very embarrassing, and even the Arthur Martins and Peter Wrights of this world would have recognized that. But, apart from the fact that he should never have been recruited by MI5, Blunt should never have been treated so leniently when he was found assisting Leo Long in espionage in 1944, should never have been trusted during the Burgess-Maclean fiasco, should never have been used as a ‘consultant’ in the Philby business, or by Liddell in further investigations of dangerous communists, and certainly should never have been sent to Beirut to warn Philby of Elliott’s impending arrival (as the evidence strongly suggests). He should have been asked to resign his posts, have his perks and privileges taken away, and found his own new niche – perhaps even a minor chair at Liverpool University, which he might have regarded as only slightly more appealing than exile to Moscow. And this should have been effected with a promise that he would maintain his silence. The secret might still have leaked out eventually, but at least the objections to his tolerant treatment would not have been so strong. (Contrary to what Professor Sir Michael Howard claimed in a letter to the Times, Blunt was never used as channel of disinformation to the Soviets: see https://coldspur.com/double-crossing-the-soviets/ for a debunking of this absurd notion.)

Thus the policy as executed for Leo Long and John Cairncross – and maybe others unknown – and planned for Kim Philby, was a misguided show of passivity and evasion.

The Weakness of Roger Hollis:

Roger Hollis must be held accountable for much of this failure, since most of it occurred on his watch (1956-65). One must recall that, during this eventful year of 1963 (so far as the actions surrounding Blunt, Straight and Cairncross were concerned), Hollis also had to deal with the Profumo case. This had problematic outcomes: Stephen Ward had committed suicide, while John Profumo had been let off extremely lightly, considering the misdeeds and lies he undertook. Ewing, Mahoney and Moretta (see above) make a strong case that, even though Hollis was cleared by Lord Denning in the latter’s inquiry, Hollis had in fact acted very indolently in not informing the Home Secretary of what MI5 knew about Profumo, Ward, Keeler and Ivanov, and that he had avoided the truth that it was an issue of ‘defending the realm’.

Hollis clearly had more important matters on his mind. But that is no excuse: as the saying goes, ‘it came with the territory’. Hollis was yet another senior MI5 officer who let himself be taken aback by events, and had not worked out what the agency should do if unpleasant surprises came along. Maybe that was an outcome of MI5’s exact statutory footing’s being indistinct, but that had been clarified to a certain extent by the Findlater Stewart report at the end of the war, and the following Attlee and Maxwell Fyfe Directives. Hollis had enough time to attempt to resolve such issues, but preferred to keep his head down, and try to maintain a quiet life. Moreover, Hollis was apparently far too much under the influence of Dick White, with MI6 officers also appearing to be meddling in MI5 affairs far more than was suitable.

Thus the strategy over Blunt and Cairncross, of trying to keep the secret to as small a number of persons as possible, was bound to fail in the long run. It was one thing to conceal important facts from the incoming and possibly naïve Prime Minister Alec Douglas-Home (where Hollis was abetted by the Cabinet Secretary, the Home Secretary and the Attorney General), but the policy of deceiving junior officers, with their natural inquisitiveness and interest in internal gossiping, did not inspire trust as the story went around. Perhaps it is surprising that the secret remained in the private sphere so long as it did. Hollis died in 1973, and thus did not live to see his handiwork unveiled.

The Duplicity of Dick White:

Dick White’s contribution to the whole affair is controversial, even sinister. He had recommended Roger Hollis as the officer who should succeed him when he was appointed head MI6 in 1956. And maybe Hollis looked for guidance from his mentor when he took over the reins as director general. In any case, White appeared to maintain a very active involvement in MI5 affairs. No doubt he kept in close touch with Arthur Martin, who had been a loyal servant to him during the machinations of the Burgess-Maclean business. It is White who encourages Martin to pursue the Mitchell inquiries, and Hollis is regularly consulting with White, for example when the information from Straight arrives. It is White who encourages Hollis to fly out to Washington to explain the details of the Mitchell case to the FBI and the CIA.

Yet White apparently did not have a high opinion of Hollis’s capabilities. Chapman Pincher, in Treachery (p 428), cites a letter that White wrote to Hugh Trevor-Roper (Lord Dacre) in 1984: “Hollis was never interested in CE (counter-espionage) work, having one of those crabbed minds that prefer protective security measures to the fun of sniffing things out.” This was a highly unprofessional statement for White to make. Either he deliberately wanted MI5 to fail under the leader he had recommended, or MI5 had no other candidates who could have competed. But, if White had always had this opinion of Hollis (‘never interested’), it would have been incumbent upon him to recommend that someone be appointed from outside. (Cleveland Cram dubbed Hollis ‘the biggest dolt to come down the pike in years’.) After all, there had been two recent precedents for such a decision (Petrie and Sillitoe).

White had as much to lose in the Blunt business as anyone, having been the sole surviving officer in the agencies who had witnessed his recruitment in 1940, and he had been hoodwinked by him and his cronies ever since. White had believed that Philby was guilty back in 1950, or earlier, but had avoided MI5-M6 strife by channeling his accusations through the FBI. On taking over MI6, he had banished Philby, but the spy had managed to get back on the books as an unofficial contributor. Now Philby had disappeared, and it suited White to suggest that someone within MI5 (where the main molehunt was occurring) had been responsible for leaking the news of the impending visit by Nicholas Elliott. Gordon Corera writes (p 194) that ’it was Martin’s theory that his old foe had been tipped off that most intrigued the MI6 chef’, but, in light of Blunt’s visit to Beirut, it is safe to assume that White played along with Martin, and saw a great opportunity for camouflage.

So was White a serious believer in the presence of an ELLI in MI5, whether Mitchell, Hollis, or anyone else? I doubt it. Yet he very quickly turned against Hollis. When Hollis fired his troublemaker, Martin, White quickly recruited him. Shortly afterwards, Hollis’s deputy, Furnival Jones, after discussing the problem with Dick White, agreed that an inter-agency investigative committee needed to be set up, and White convinced a reluctant Roger Hollis that it was a good idea Thus the FLUENCY sub-committee, under Peter Wright’s chairmanship, was established, and it soon had to consider whether Hollis himself was a spy. The outcome was inevitably destructive, and may have contributed to Hollis’s early death in 1973.

White retired from MI6 in 1968, somewhat detached from the fray that he had set in motion. In 1974, however, after the less eventful tenure of John Rennie, a fresh anti-MI5 thrust emerged from MI6. As Professor Glees described in The Secrets of the Service, Stephen de Mowbray of MI6 (a member of the FLUENCY team) ‘broke his cover’ to write an article in Encounter magazine that revivified all the theories of Soviet subversion within MI5, and the probable guilt of Roger Hollis. The new head of MI6 was Maurice Oldfield, White’s molehunt facilitator from Washington.

Authorised History:

My final observations concern the phenomenon of authorised history – and specifically Christopher Andrew’s work. Readers who are swayed by my theories about the confessions will agree that the exposition in Defend the Realm is, in the coverage of Blunt and Cairncross, erroneous. It contains misrepresentations and oversights. Yet Andrew’s book is generally regarded as biblical in its authority, even to the extent that historians and biographers will ignore evidence before their own eyes that suggests an alternative story in favour of Andrew’s account. In May 2017, in my piece ‘Officially Unreliable’ (https://coldspur.com/officially-unreliable/), I laid out my objections to authorised histories in general, with Defend the Realm as one of my examples, and I withdraw nothing I wrote at that time. In fact my message is reinforced by the Blunt case.

In many respects Defend the Realm is an impressive work, with a masterful synthesis of complex issues. Yet it is deeply flawed, primarily in its indiscriminate use of dubious sources, and in its vast number of citations of anonymous archival records that cannot be verified independently. The passage describing Blunt’s confession is the latest notorious example. I see no reason why the document that is claimed to play such a major role in Andrew’s narrative, and those related to it, should not be released by MI5, so that independent historians could make their own assessment of their authenticity, and how they shed light on the events of 1963 and 1964. Moreover, I suspect that Andrew, and those who assisted him, may not have maintained a scrupulous cross-reference of documents and citations so that a full concordance could be constructed if and when the authorities see fit to make the archival material accessible. (It is not as if relevant Freedom of Information requests can easily be made, as there are no identifiers to refer to.) I made this point in my original script, and I know at least one distinguished historian who maintained such a system in his researches and writing.

The scope of Defend the Realm is surely too ambitious. So much released material exists that a new History could probably be divided up into volumes covering the stewardship of each Director-General. That would have to be complemented by a judicious and methodological treatment of other literature (memoir, biography, other government sources, etc.). I happen to believe that my own contributions in this area, covering such as Fuchs and Peierls, Agent Sonya, Dick White and the Burgess-Maclean affair, Liverpool University, the RSS and the Double-Cross System, the LENA spies, VENONA and HASP, the Portland Ring – and now Blunt and Cairncross – constitute a valuable corpus of material that should be used in any fresh enterprise.

Yet it is difficult to see how such a programme would evolve. For example, despite the best efforts of Professor Glees and me, it has been a struggle to gain serious attention over the hubbub of publicity given recently to Agent Sonya, and correct Ben Macintyre’s story. Serious historians do not seem to want to challenge the establishment history of MI5. A few years ago, the FBI gave serious airtime to the debate about ELLI and Roger Hollis (see https://fbistudies.com/2015/04/27/was-roger-hollis-a-british-patriot-or-soviet-spy/ ), but it fizzled out. I do not see any mechanism in the UK for performing a similar exercise on MI5 molehunts, but, if anyone decides that it should be pursued, I am very willing to contribute.

Late-Breaking News!

I have not yet received my copy of the February 26 Times Literary Supplement in the mail, but my on-line colleague Michael Holzman has just informed me that the following item appears on the back page:

‘Antony Percy writes from Southport, NC, to point out a near-enough coincidence: as we were quoting John le Carré (January 22) wondering if the future might bring about a “fairer, less greedy world” than the present (with its “jingoistic” England – “an England I don’t want to know”), Hunter Davies was recalling in The Times (January 21) how le Carré, fifty-odd years ago, “handed over £2.6 million to a tax avoidance schemer in the West Indies – and lost it all”. The top rate of tax at the time, Mr Percy omits to mention, was 95 per cent.’

What the columnist fails to consider is that, if John le Carré had been serious in wanting to contribute to a ‘fairer, less greedy world’, he would presumably (unlike me) have supported the government’s ‘progressive’ tax policies, as it obviously would have been far wiser in spending (ahem, ‘redistributing’) his hard-earned income than he himself was.

New Commonplace entries can be found here.