I use this bulletin to update my story of two Cambridge Spies – Donald Maclean, one of the notorious set of 1930s communists, and Willem ter Braak, a member of the Abwehr’s LENA group who underwent a mysterious death in Cambridge in April, 1941. Because of its size, and the distinct subject areas it addresses, I have decided to split this report into two sections, even though there are areas of overlap. Part 2 can be seen here.

Donald Maclean

First, a recap. In ‘Donald Maclean’s Handiwork’ (coldspur, December 2018), I analysed the peculiar and provocative indications that Andrew Boyle and Goronwy Rees had left behind concerning the possible stronger clues that MI5 may have received to the identity of the Foreign Office employee identified (but not named) by Walter Krivitsky as a Soviet spy. Krivitsky had named (John) King as a spy in the Foreign Office, but only hinted at the person who was the ‘Imperial Council’ spy. Two strong hints appeared: the first was Rees’s belated identification of a photographer called ‘Barbara’, who had testified to Maclean’s abilities with a camera, and Rees’s suggestion that Krivitsky had recognized Maclean’s handiwork when he (the GRU officer) had last been in Moscow in 1937. The second was an enigmatic reference to a diplomat called ‘de Gallienne’ in a note in Boyle’s ‘Climate of Treason’, which attributed to him an early reference to Krivitsky and the latter’s description of the persona of Maclean.

At the time, I questioned the reliability of Rees’s deathbed testimony. Rees had historically been a highly dubious witness, and the posthumous account of the conversation he had had with Boyle, which appeared in the ‘Observer’, was a typical mixture of half-truth, downright lies, and questionable accusations. It sounded as if ‘Barbara’ was an inspired invention. As for ‘de Gallienne’, the name was probably wrong. I had discovered a diplomat called ‘Gallienne’, who was chargé d’affaires, and then Consul, in Tallinn in Estonia at the time, but it seemed a stretch to connect this official with Krivitsky and the information that the defector provided to the FBI or to his interrogators from MI5 and SIS in London.

And then – a possible breakthrough. I thus pick up the story and analyse the following aspects of ‘Donald Maclean’s Handiwork’:

- The identity of ‘Barbara’, and her relationship with Maclean;

- The investigations by MI5 and MI6 into Henri Pieck’s exact involvement in handling Foreign Office spies;

- The missing file in King’s folder, and how it relates to anomalies in the story;

- The Foreign Office’s obstinacy in the face of Krivitsky’s testimony;

- The possible contribution of Wilfred Gallienne, diplomat, to the investigation; and

- Boyle’s apparent reliance on Edward Cookridge and Guy Liddell for information.

‘Barbara’

As I recorded soon after I posted the December story, the author of the recent biography of Donald Maclean, Roland Philipps, suggested that ‘Barbara’ could well be Barbara Ker-Seymer, a well-known society photographer of the 1930s. Astonishingly, I had read of this woman only a week beforehand, in Hilary Spurling’s biography of Anthony Powell, Dancing to the Music of Time, where, on page 108, she describes Powell’s friend in the following terms: “As observant as he was himself, she was well on the way to becoming one of London’s most up-to-date photographers . . .”. Yet the Barbara-photographer connection with the Rees testimony had eluded me. A quick search on ‘Ker-Seymer & Donald Maclean’, however, had led me to a portfolio of her photographs at the Tate. The gallery contains an impressive set of artistic names from the 1930s, and on the album page 12 at https://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/items/tga-974-5-5/ker-seymer-photograph-album/14, alongside Cyril Connolly, can be seen a photograph of Donald Maclean, in Toulon, probably in the summer of 1936. Yet in the annotations provided by the Tate, a question mark appears next to Maclean’s name.

Other communists appear in the album. On page 19, Goronwy Rees can be seen at the 1937 May Day march, and on page 25 two photographs of ‘Derek Blakie’ appear. The editor has not seen fit to correct the script here, but the person is certainly Derek Blaikie, who accompanied Guy Burgess to Moscow in 1934. Blaikie had been born Kahn, attended Balliol College, Oxford, and become a friend of Isaiah Berlin, who suggested in a letter to Stephen Spender that he was a rather dangerous Marxist. Kahn changed his surname to Blaikie in 1933. According to Stewart Purvis & Jeff Hulbert in The Spy Who Knew Everyone, Blaikie’s primary claim to fame was to write a letter to the Daily Worker, just before Burgess’s introductory talk on the BBC in December 1935, in which he explained that Burgess was ‘a renegade from the C.P. of which he was a member while at Cambridge’. This letter, suggesting that Burgess’s conversion to the far right was a ruse, was intercepted by MI5, and entered in Blaikie’s file, but then apparently forgotten. Significantly, Helenus (‘Buster’) Milmo, the QC who interrogated Philby in December 1951, had access to this letter. In his following report Milmo quoted another passage, which ran as follows: “In “going over to the enemy” Burgess followed the example of his closest friend among the Party students at Cambridge who abandoned Communism in order successfully to enter the Diplomatic Service.” A massive tip was not followed up.

I asked Mr Philipps about the collection. I was amazed to learn that he was not aware of its existence and availability. Furthermore, when I followed up about a week later, he told me that he had not yet inspected the display, even though, for reasons he would prefer I not disclose, the albums contained several photographs that would have been of intense interest to him. I was a bit puzzled by the fact that the author of A Spy Named Orphan, which is promoted as ‘the first full biography of one of the twentieth century’s most notorious spies, drawing on a wealth of previously classified files and unseen family papers’ would show such a lack of curiosity in his subject. He then added: “ . . . I also don’t think that the man in that one is DM. He doesn’t seem tall enough or have quite the face and hair. Also, I didn’t find him mixing in that society much – he didn’t care for Burgess and I don’t know of any records of his connections with Rees and his rather more social circle.”

Is that not remarkable? That a biographer, without inspecting the photograph personally, instead relying on the on-line image, would distrust the evidence that the photographer herself had recorded? How the figure’s height can be determined when he is squatting, or how his hair could confidently be judged as unrecognizable some eighty years on, strikes me as inexplicable. The evidence for Philipps’s conclusion about Maclean’s social activity is sparse: if we consult his biography, we can find only a few examples of the spy’s life in this period. We learn that ‘wearing the regulation white tie and tails, with his silk-lined opera cloak draped around his tall figure, he escorted Asquith’s granddaughters Laura and Cressida to dances . . .’, and that he was Tony Rumbold’s best man in 1937. Yet Maclean also mixed in bohemian circles – especially after he moved to Paris in 1938. E. H. Cookridge wrote, in The Third Man, that Maclean ‘became a regular visitor to Chester Street’ (Guy Burgess’s residence), and that it was at such parties that he became a habitual drinker. (Cookridge’s anecdotes are, however, unsourced. For some reason he did not consider that Maclean was a Comintern agent at this time.) Nevertheless, no matter how well (or poorly) Maclean and Burgess got on, it would have been considered poor spycraft for them to have gathered together too frequently. As Philipps himself writes: “Acting on Deutsch’s instructions, Maclean never mentioned Burgess or Philby or spoke to them on the rare occasions when their paths crossed at parties.” Moreover, Maclean became a close friend of the louche Philip Toynbee. Thus I find Philipps’s instant dismissal of Ker-Seymer’s evidence, and lack of interest in pursuing the lead, astonishing – mysterious even.

As for Rees, his (and Blaikie’s) presence in the album only reinforces the fact that the Ker-Seymer circle included leftist enthusiasts. Philipps has told me that Ker-Seymer ‘adored Rees, but was wary of him’, while a letter to the Independent in 1993, after an obituary of Ker-Seymer was published, recalled Barbara with her ‘old friend Goronwy Rees sitting on a banquette during World War II’. Yet the connection sadly does not advance the investigation very far. The inveterate liar Rees may have bequeathed us all a truth when he declared that he and Maclean did indeed have a mutual friend Barbara, who was a photographer, but his testimony does not show that her studio was used by her, or by Maclean, as a location to take photographs of purloined Foreign Office documents. And her studio was not in Pimlico. So why would he bring the subject up? The quest continues.

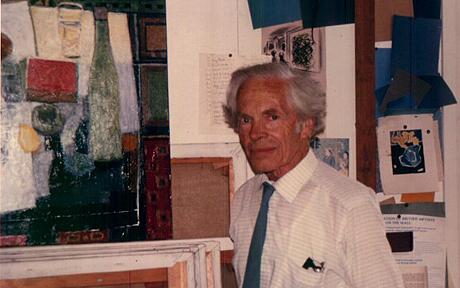

Henri Pieck and Krivitsky

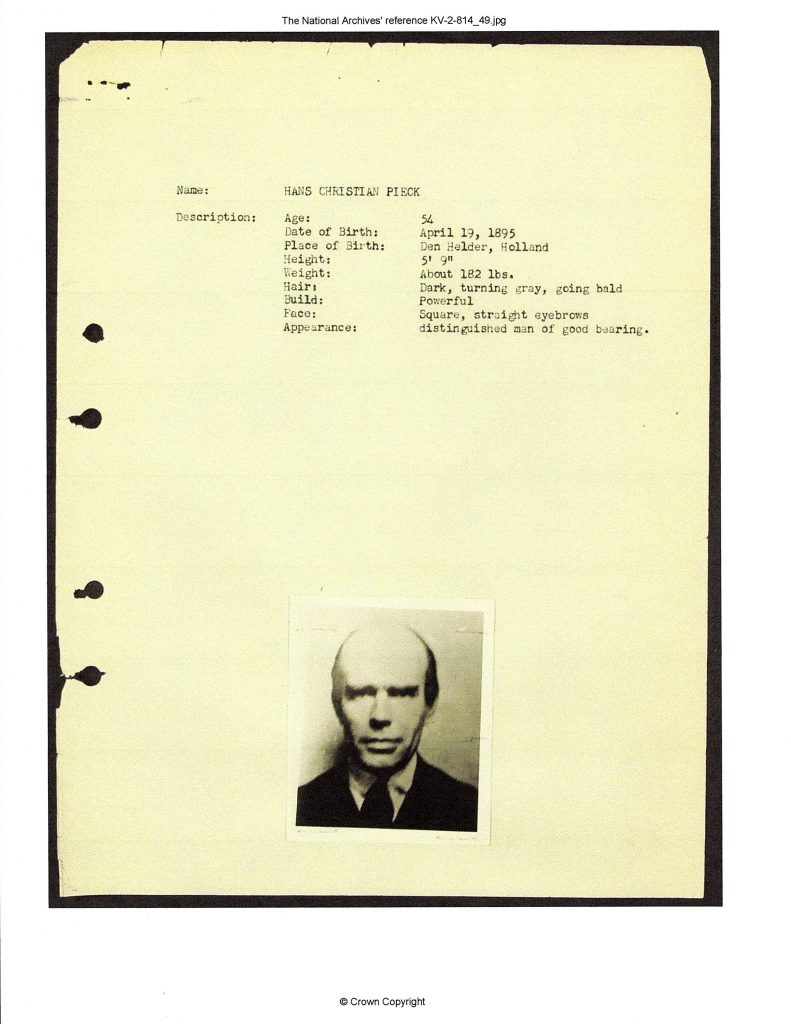

The career of Henri Christian Pieck, the Dutchman who recruited John King, and then handled him until his operation was suspected by British Intelligence, merits closer analysis. Ever since MI5 and SIS learned from Krivitsky that there was a second spy in the Foreign Office (the ‘Imperial Council’ source), they speculated whether Henri Pieck may himself have run both agents. This investigation picked up after Krivitsky was murdered in Washington in February 1941, especially since Pieck had made a bizarre attempt to leave Holland and work as a cartoonist for the Daily Herald in early 1940. Nothing came out of this venture, but, after the war, when MI5 betook itself to reinspect the vexing case of the Imperial Council spy, with new minds on the case, the evidence was re-examined for the purpose of verifying whether there were physical and logical links between Pieck and the unidentified traitor.

One might ask why Krivitsky, if he was so unwilling (or unable) to offer his interrogators the identity of the Imperial Council spy, but had readily provided them with the name of John King (a mercenary), was so forthcoming about Pieck (a dedicated communist, who had worked for Krivitsky in the Hague). The most probable explanation is that Krivitsky believed that Pieck was no longer working for the Soviets. Pieck had had to withdraw from handling King in early 1936, and to retire to Holland, although he did make one or two discreet visits back to the UK in 1937. Yet Krivitsky did suggest that, if Maly were still alive (of course, he was not), because of the good relationship that existed between Maly and Pieck, there was a possibility that Pieck could be resuscitated at some stage. Telling the British authorities about his role would surely have scotched that: it was not as if Pieck were a shadowy character without a public presence.

A certain amount of animosity existed between the two, however, which might explain Krivitsky’s diminished loyalty. Krivitsky considered Pieck’s expense account for the entertainment and bribing of his agents and friends in the cipher department of the Foreign Office, and others, lavish. When Krivitsky had gained an ideologically committed spy in the Foreign Office (Maclean), he told Pieck, who had had to leave London soon after Maclean was recruited because his ‘safe’ house was no longer secure, that he now had a much cheaper and more effective source. Pieck’s replacement as King’s handler, Maly, then recruited a further Foreign Office source, John Cairncross, before he was recalled to Moscow in the summer of 1937. King’s role thus became markedly redundant, and he was abandoned. Krivitsky may have taken pleasure in that. He was also critical of Pieck’s ingenuousness about the approach in Holland by the ex-SIS operative Hooper (who had ostensibly been fired), saying that it might well be a plan to infiltrate the GRU. He considered Pieck ostentatious and indiscreet: his spycraft was poor.

From his side, Pieck much later told MI5 that Krivitsky’s account of the attempt to acquire arms for the Spanish Republicans in the autumn of 1936 was false, even though Krivitsky’s presentation probably shows Pieck’s performance in better light than what in fact occurred. Krivitsky had described Pieck’s role to his interrogators without naming him, and had not specifically identified the ‘Eastern European capital’ in which the transaction was attempted as Athens. Perhaps trying to boost his own track-record, Krivitsky did not explain that the attempt made – when Pieck was accompanied by the Englishman William Fitzgerald – was a total failure. (The exchange was also reported back to Menzies, the head of SIS, by the local ambassador.) Yet one can also not trust Pieck’s account of his dealings with Krivitsky. He claimed that Krivitsky ordered him to kill Reiss: that is unlikely. Like Philby with Franco, he would not have made a reliable hitman, as the NKVD files attest on both of them. Finally, Pieck told his interrogators that he disliked Krivitsky and his wife, so there was clearly no love lost between them. Thus it seems safe to conclude that Krivitsky felt free in giving to MI5 and SIS a name to whom he owed no particular loyalty, and whom he felt they could pursue without any further exposure.

It did not seem to occur to MI5 that, if Pieck had indeed handled both spies, it would have been unlikely that Krivitsky would have talked so freely about him, as Pieck might have been able to reveal information which Krivitsky was clearly reluctant to share. But MI5 and SIS (the latter becoming involved because the breach occurred in the Foreign Office, and was being controlled from overseas), showed a track-record of sluggishness in following up the leads. They were constantly one step behind, and never resolute about what to do next. For example, the SIS renegade Jack Hooper knew, by January 1936, through Pieck’s business associate Conrad Parlanti, of the meeting-place in Buckingham Gate, and even told Pieck, at a house-warming party held by the latter in the Hague later that month, that MI5 knew he was a Communist and that he had been under surveillance in Britain. MI5 and Special Branch had supposedly been trailing Pieck all year. By then, of course, Maly had already replaced Pieck as King’s handler/courier, as Pieck no longer had legitimate reasons for staying in London, and it was taking too long for material to get to Moscow when Pieck had to take it with him to the Hague each time. Just as with Maly shortly afterwards, MI5 and Special Branch would let Pieck slip through their fingers.

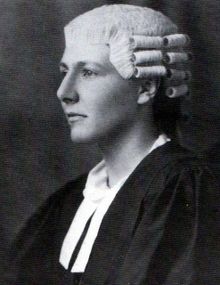

What is remarkable about this period, and highlights how unprepared MI5 and SIS were when they were faced with the evidence of an ‘Imperial Council’ spy, is the mess that Valentine Vivian (of SIS) and Jane Sissmore (of MI5, who became Jane Archer when she later married, on the day before war was declared) made of the Pieck investigation when they picked it up again in 1938.

Vivian and Sissmore Move In

Two years after Pieck supposedly had left the country for good, Vivian was exchanging memoranda with Sissmore about Pieck’s role in Soviet espionage. It appears that Sissmore was taking stock of the situation after the successful, but highly time-consuming, prosecution of Percy Glading, who had been passing on secrets from Woolwich Arsenal to his Soviet contacts. She had played a key role in preparing the case, and Glading was sentenced on March 14, 1938. Glading’s diary had triggered some valuable leads, including one that led MI5 to Edith Tudor-Hart. Pieck was another piece in the puzzle, but his exact role was still a mystery. We should remain aware that, through the agency of Hooper in early 1936, the Intelligence Services had learned of Pieck’s Buckingham Gate location, and what it had been used for, and the fact that Foreign Office documents had been ‘borrowed’ for photographing. The process was a mirror of the Glading exercise. Moreover, MI5 and SIS knew that Pieck had met Foreign Office clerks in Geneva in the early 1930s, and it could trace who those individuals were.

Given the later painstaking process that the CIA and MI5 undertook, in late 1949 and early 1950, to try to discover who in the Washington Embassy had access to the report that finally gave Maclean away, it is surprising that a similar procedure was not initiated on the important report that the ‘Imperial Conference’ spy had passed on. In fact, as her conversations with Krivitsky in early 1940 show, Jane Archer identified it as a secret SIS report, which had been distributed to several Foreign Office contacts by MI5. The exchange is vivid, as her report to Vivian in early February 1940 informs us: “In accordance with your instructions I took Thomas [Krivitsky] yesterday the photographed copy of the cover of the C.I.D. Imperial Conference document No 98., the last page and the portion dealing with the U.S.S.R. As soon as I showed it to him Thomas said ‘Yes, I have seen this cover several times in Moscow, in white on black form, in the office of the man who receives the material.’ Yet when Krivitsky read the text about the Soviet Union, it was unfamiliar to him.

Archer then tried something else. “I then showed him part of the very secret S.I.S. document of 25.2.37, particularly the paragraph on Page 2 marked (1). He read the first few lines and then said ‘this is the document’.” Archer did not provide a precise pointer to the document in question, but we can learn more about it from elsewhere in the Krivitsky file, at KV 2/405-1, a passage that is worth quoting in full. We find that, much later, on May 1, 1951, A. S. Martin, B2B, wrote: “Xxxxxxx xx [redacted] S.I.S showed me on 28.4.51 extracts from a file held by Colonel Vivian from which it was clear that in 1940 SIS had identified document which K had seen in Moscow. Its title was ‘Soviet Foreign Policy During 1936’; its reference was Mo.8 dated 25.2.37. It had been circulated by S.I.S to FO Northern Department, FO Mr. Leigh, War Office (M.I.2.b, M.I.3.a, M.I.3.b, M.I.5 and the Admiralty. Xxxxxxx told me that he had been unable to trace the document in the S.I.S. registry and he presumed that it had been destroyed. Xxxxxxx had passed the description of this document to Mr. Carey Foster of the Foreign Office. I subsequently found that the M.I.5 copy of this document was filed at 1a on SF. 420/Gen/1.’ (from). A handwritten note indicates that the document was in ‘K Volume 1’. If K means ‘King’, that was a file that was destroyed (by fire? – see below). Thus the investigation fizzled, and, as each year passed, the trail became colder.

In any case, Vivian’s insights on Pieck were seriously wrong, out of inattention or laziness. In his letter to Sissmore of March 25, 1938, he wrote: “Pieck has filled much the same position in this country as the ‘PETERS’ (Maly) and ‘STEVENS’ of the recent GLADING case. . . . If his statements are to be believed, he had established himself with certain Foreign Office contacts by the end of 1935 or beginning of 1936, and was able to get the regular loan of documents, which were photographed with a Leica camera and apparatus at an office, which he had taken in, or in the vicinity of, Buckingham Gate.” The ‘has filled’ is deplorably vague, suggesting that Pieck has recently played a role similar to that of Maly and was probably still active, and one of Britain’s most senior counter-intelligence officers appears to think that the purloining of state secrets is an act akin to the borrowing of library books. Should Vivian, moreover, have perhaps developed a mechanism by which he would first distrust the declarations of Soviet agents? Why would they tell the truth? He then shows his disconnectedness by representing the time when Pieck was withdrawn as the time that he started his conspiratorial work with the Foreign Office clerks.

What is even more surprising, given Sissmore’s sharpness and Vivian’s relative dullness, is her not correcting Vivian. MI5 had apparently done nothing in the interim: it must surely have informed Alexander Cadogan, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, some time back, because he refers to the leakages in his diary. Yet no suspects had been interviewed, security procedures had not been tightened, and, for all that MI5 knew, the extractions of secret documents could still have been going on. Just because Pieck had also told Hooper that he was out of the espionage game, why should MI5 believe him, as SIS apparently did? Should they not have attempted to verify? Had they been tracking his movements? After all, they had also learned that Pieck had made his unsuccessful bid to acquire arms for the Republicans in Spain when he and Fitzgerald approached the Greek government in the summer of 1936, as the British Embassy in Athens had reported the encounter to SIS. Pieck was thus still clearly active in the Soviet Union’s cause.

Archer wanted to bring Pieck over from Holland to talk, so she and Vivian must have regarded his commitment to Communism as weakening, and considered that he might now be willing to help his erstwhile target. This thought was balanced by a strange request from the Dutch Government. Vivian told Sissmore that his agent in Holland had learned from the Dutch police that Pieck ‘travelled frequently between Holland and England in 1937 and is believed by them to have had the confidence of a high official of Scotland Yard’. Yet his permission had now been withdrawn: they wanted to know why. Vivian could not add much, explaining that they had not been in touch with Hooper since 1935, but did not appear nonplussed by the Scotland Yard linkage. Did he perhaps think that was normal practice for Soviet agents? Moreover, he made an obvious error, as Hooper had had the significant meeting at Pieck’s apartment in January 1936. Was Pieck also stringing the Dutch police along?

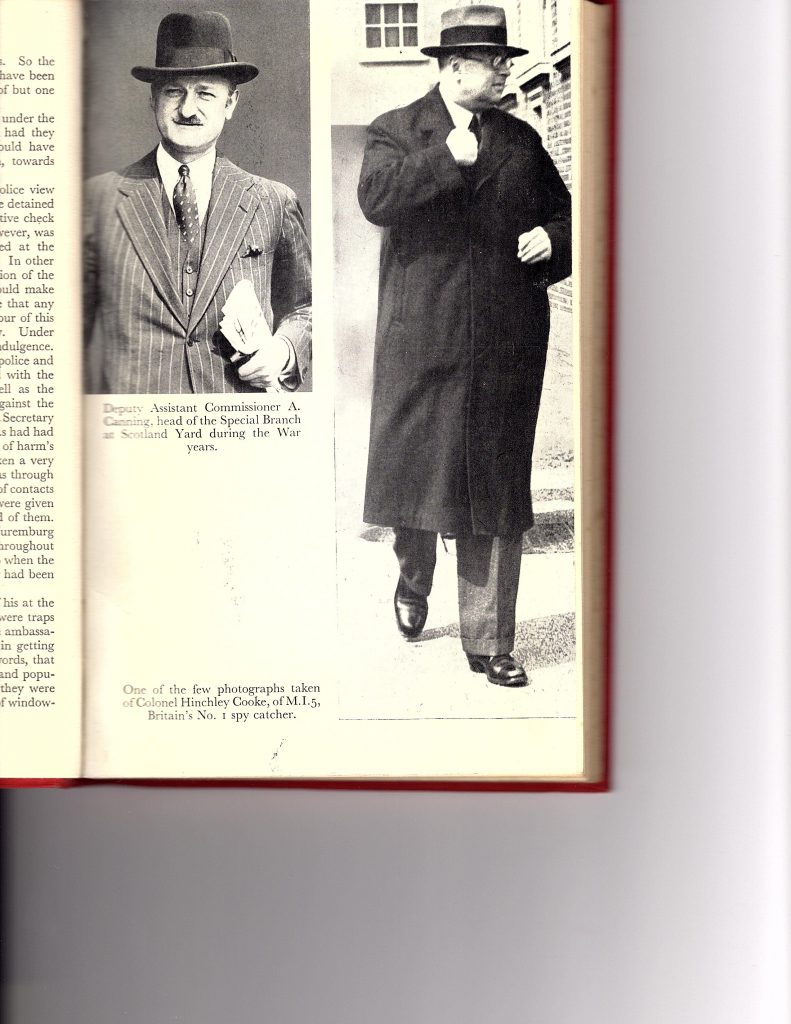

Moreover, if that assertion about Pieck’s travel habits was true, how on earth had he managed to fly or steam in to England under the noses of MI5 without being detected? Why did Vivian not express surprise at this revelation? After all, this was a man whom Special Branch had been watching assiduously in 1935, although they never spotted anything untoward. Sissmore had written to Vivian in April 1935 that they could not detect anything suspicious about his visits, but had noted that Pieck should be watched ‘if he ever came over again’. One might expect at least that all ports of entry were being watched. Sissmore next made an inquiry to Inspector Canning of Special Branch on September 2, 1938, and her words are worth quoting verbatim: “It is reported that Pieck is an espionage agent working on behalf of the Soviet Union, and is believed to have at one time filled the place of Paul Hardt (Maly) in the Glading espionage group in this country. He has paid frequent visits to England in the past, but is at present in Holland.”

This is an extraordinarily tentative and detached statement by Sissmore, in its vagueness about dates and use of the passive voice: one explanation might be that she had been unduly influenced by Vivian. Yet her letters to him do not indicate that she was in awe of him: she treats him very much as an equal, and he responds likewise. After all, who was authorized to perform the reporting, and articulating beliefs, if not Sissmore herself? And how could she get the timetable of events so direly wrong, indicating that Pieck had replaced Hardt (Maly), when she knew that Maly, who in fact had replaced Pieck, had left the United Kingdom for good in June 1937, barely escaping capture by Special Branch, and that Pieck’s most frequent visits to Britain had occurred in 1935? (She also unaccountably records this year incorrectly in her report on Krivitsky.) Did she really believe that Pieck had started up his subversive activities again in 1937, simply because of what the Dutch authorities said? And should she not have been a bit more careful in approaching the Metropolitan Police, if Pieck was claiming he had some kind of protection on high at Scotland Yard? Was she simply all at sea? It is an untypically undisciplined performance by MI5’s star counter-espionage officer. One could perhaps surmise that she was being directed to hold back. It is almost as if she were sending a coded message in her reports: ‘This is not my true voice’.

Inspector Canning was then able to inform Sissmore that Pieck had made two visits to England, via Harwich and Folkestone, towards the end of 1937, but these passages had gone completely unnoticed by MI5. What is more, their log showed that Pieck made fifteen visits to the UK in 1935, making his final departure for a while on February 14, 1936, not returning until October 14, 1937. The last trip was a lightning event, since he arrived on February 13 at Dover, and left from Harwich the following day, probably hoping that the change of ports would avoid immediate suspicions. So what did Vivian mean when he said that Pieck established contact at the end of 1935, or early in 1936, if the suspect then disappeared for twenty months? It appears that no detailed chronology – a sine qua non of successful detective work – had been created. The archival record is disappointingly blank after this – until the stories start to appear from Krivitsky and Levine a year later. Perhaps Sissmore and Vivian realized they had severely mishandled the job.

For those who relish

intrigue and conspiracy theory, they might find an explanation for Vivian’s

enigmatic behavior elsewhere. A Dutchman, F. A. C. Kluiters, has written an

article that suggests that Jack Hooper was a double-agent for the Abwehr and the NKVD, and was probably being

used by Claude Dansey to pass on disinformation to the Germans. The article can

be seen at:

https://www.nisa-intelligence.nl/PDF-bestanden/Kluiters_Hooper2XV_voorwebsite.pdf I do not recommend it lightly, as it is so

convoluted that it makes a typical chapter of Sonia’s Radio seem like Noddy

Goes to School. One day I may attempt to analyze this particular tale, but

all I say now is that, if this scheme actually had any substance, and was

indeed the creation of Claude Dansey, his arch-rival Valentine Vivian would

have been the last person in British Intelligence to know what was going on. Vivian

and Dansey were at daggers drawn on many issues, not least of which was the

treachery of Jack Hooper, and his subsequent re-engagement after being fired.

Vivian may well have been set up to perform a mea culpa over Hooper’s betraying to the Abwehr a spy named Dr.

Krueger, who had been providing the British with details of German naval

construction for some years.

Yet such theories of double-dealing should not be abandoned as irrelevant to this quest. In the authorised history of MI5, Christopher Andrew (who mentions Pieck on a couple of pages, but does not grace him with an Index entry) states that SIS was dangerously misled by Hooper, who, ‘it was later discovered, was in reality the only MI5 employee who had previously worked for both Soviet and German intelligence (as well as SIS)’. Sadly, and conventionally, Andrew does not provide detailed references for his sources from the Security Service archive, ascribing proof of King’s guilt to interrogations of German prisoners after the war, but he indicates that SIS made a poor decision in re-hiring Hooper in October 1939, after he had worked with the Abwehr in 1938-39. What is remarkable is that Keith Jeffery, in the authorized history of SIS, has only one line about Hooper, stressing instead the treachery of a Dutchman recruited by the SIS office in the Hague, Fokkert de Koutrik. I suspect Hooper’s role in the King/Pieck story has not been fully told. It is not often one comes across an agent with such multiple allegiances – especially one who survived. (Another is the mysterious Vera Eriksen, who landed alongside Druecke and Walti in Scotland on September 30, 1940, but escaped the death penalty. A book on her is about to be published.) This one will clearly run and run. Is anyone out there, apart from Mr. Kluiters, researching his story? (I notice that four files on Hooper were released by the National Archives in November 2017: they must form a valuable trove, and I look forward to inspecting them some time.)

A Fresh Look

The story moves forward to 1940, to the Krivitsky interrogations, and beyond. As readers of Misdefending the Realm will recall, Jane Archer was already being eased out of her job as MI5’s leading officer in communist counter-intelligence when she compiled her report on Krivitsky in March of 1940, and she was replaced by her subordinate, the unremarkable Roger Hollis. 1940 was a difficult year for MI5: the transition from Chamberlain’s administration to Churchill’s, the sacking of its Director-General, Vernon Kell, the imposition of the Security Executive layer of management, the insertion of unqualified supervisors, and the fear of invasion accompanied by the ‘Fifth Column’ panic, with the stresses of making thousands of internment decisions. Little attention was paid to concealed communists, with Hollis’s activities directed more at the possible unreliability of communists in the factories, and Guy Burgess doing a skillful job of directing energies away from his conspirators in government. During 1940, there were occasional communications about Krivitsky between Vivian and Cowgill of SIS, Harker, White, Liddell and Archer of MI5, and even the occasional guest appearance from the sacked supremo Kell. Krivitsky was in Canada for most of the year, and attempts were even made to contact him directly. Yet no apparent effort was made to pick up the unresolved matter of the ‘Imperial Council’ spy.

Unsurprisingly, we cannot read any reaction within MI5 to the announcement of Krivitsky’s death. Even Guy Liddell could not stretch to recognizing the event in his diaries: true, an item in his February 11, 1941 page has been redacted, but there is no corresponding entry for ‘Krivitsky’ in his Index. A half-hearted attempt was made, however, to investigate the Pieck case in the light of the disturbing murder set up to look like a suicide. In the same month, Pilkington in B4C tried to track down Pieck’s architect friend, Stuart Cameron Kirby, who had accompanied Parlanti in 1934 to see Pieck in Paris. In April, Pilkington eventually interviewed Kirby in Cambridge, where he had secured an impressive-sounding sinecure as ‘Home Office Assistant Regional Technical Advisor’, but nothing came of it. Two years later, Shillito of F2B (i.e. in Hollis’s new Division, split off from Liddell’s B) was requested to confirm that Pieck was still on the ‘Black List’ of dangerous communists. All thoughts of identifying the ‘Imperial Council’ spy appear to have been dispelled, however. The Soviet Union had become an ally, and all energies were directed towards the Nazis.

After the War

By the end of the war, however, the Soviet Union was accepted as the dominant threat to the nation’s security. But perhaps not by Alexander Cadogan, still Permanent Under-Secretary in the Foreign Office. Cadogan, who had been so distressed about the spies in his domain in 1939, had apparently forgotten about their existence by the autumn of 1945. Konstantin Volkov, the Soviet Vice-Consul to Turkey, approached the British Embassy in Istanbul in August of that year, offering to name nine agents who were ‘employees of the British intelligence organs and Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Great Britain’, as well as one who currently ‘fulfils the duties of the chief of a department of the English counter-intelligence Directorate in London’. As Nigel West reminds us in his new book Cold War Spymaster, Volkov’s follow-up letter was translated and sent to Cadogan himself. Rather than sounding alarm-bells in the Permanent Under-Secretary’s mind, the arrival of the message prompted an instruction simply to pass the document on to the Chief of SIS, Stewart Menzies. Likewise unable to fathom that perhaps a degree of caution was required in the circumstances, Menzies delegated the task to the head of Section IX, the group responsible for Soviet affairs, Kim Philby. Volkov was soon afterwards spirited back to Moscow and executed, and Maclean and Philby survived another shock.

A few months afterwards, in apparent ignorance of the Volkov affair (although Guy Liddell was very familiar with the incident), the possibility of a Pieck/Imperial Council spy connection was resuscitated. By then, stories had arrived about Pieck’s survival from Buchenwald. On September 13, 1946, Michael Serpell (F2C) issued a long report titled ‘The Possibility that Pieck was in Touch with the Source of the “Imperial Council” Leakage’. Serpell had quickly immersed himself in investigating Soviet espionage, and would soon become a notable player in the studies of Soviet spies. He was one of the officers who analysed the papers of Henri Robinson, the ‘Red Orchestra’ agent, that had been captured from the Gestapo in Paris after the war, and he would soon gain himself a reputation for dogged criticism of the handling of the Fuchs and Sonia cases. He was the officer who accompanied Jim Skardon to interview Sonia in Oxford in September 1947. He also interrogated Alexander Foote, recommending that he not be prosecuted for desertion, and then wrote the report on him that was distributed to such agencies as the CIA. His status was such that he was selected as the officer who accompanied the director-general of MI5, Percy Sillitoe, to Canada in March 1951.

In the case of the Imperial Council source Serpell’s instincts and objectives were correct, but his analysis wrong. He suggested that Pieck may have recruited an agent ‘at a much higher level than King’ when in Geneva, and that his large budget would have allowed for such a recruitment. Yet he slipped up badly on chronology, noting that the Imperial Council source (according to Krivitsky) had begun to become active in 1936. He assumed that the same camera at Buckingham Gate was probably used by this agent, but failed to note that Pieck had fled the country by then. He could hardly have ‘run’ the spy from Holland. In mid-stream, Serpell catches the contradiction, backtracking to claim that Pieck could have handled early examples of the photographic material. He admits that the main plank against his theory is that King described how he was abandoned after Maly’s departure in summer 1937, although he has been made aware of Pieck’s brief return to the UK in November 1937.

Serpell’s report rambles somewhat, and it is probably not worth any further inspection. Furthermore, what inevitably tainted his investigation was the fact that he and Roger Hollis had to communicate with SIS to gain information about what was going on in Holland. The officer they had to deal with was Kim Philby, who, while pretending to offer substantive support for Serpell’s inquiries, would surely have encouraged Serpell in his mistaken pursuit of Pieck as the handler of Maclean. To begin with, John Marriott of B2c was energised by Serpell’s research, especially since he provocatively admitted, in a letter to Commander Burt of Special Branch on December 12, 1946, that the idea that Pieck might have recruited other agents ‘is lent some support by our knowledge from more than one source that Government information has been communicated to the Russians since King’s retirement.’ After a meeting between the three of them, however, Marriott disagreed with Serpell. As the dispute carried on into 1947, Serpell’s arguments looked increasingly weaker: one might wonder whether he, as a tenderfoot, had been put on a false trail to give the impression of earnest endeavour. Marriott recommended dropping the investigation even though Serpell (now moved from F Division closer to Marriott as B1C) continued to disagree. Meanwhile, the prospect arose of MI5 actually being able to interview Pieck himself.

Dick White, now director of B Division, is the officer whose name appears as heading plans to bring Pieck to Britain, in the early months of 1950. After Pieck had been released from Buchenwald, the British had apparently been in touch with the Dutch authorities, and reminded them that Pieck had been a Soviet spy. It seems that a private security organisation had got in touch with Pieck, who declared that he was surprised by the Krivitsky revelations. But he also said that he was very short of money, and might be prepared to talk. After some local negotiation, however, he agreed to MI5’s terms for the interrogation, which involved no payments, but some protection from prosecution, and some conditions concerning confidentiality, and arrived in London on April 12. What is extraordinary is that, in November 1949, Pieck had made a visit to London, in a search for help with his embryonic exposition business, without MI5’s knowing about it.

Pieck and Vansittart

Another mysterious dimension to Pieck’s relationships with British officials needs to be explained, however. Before the war, Pieck had made puzzling references to his association with Sir Robert Vansittart, a very prominent figure in the Foreign Office. Vansittart had been the Permanent Under-Secretary until 1938, when his continued vigorous opposition to Germany’s aggressions resulted in his being ‘kicked upstairs’ to the purely symbolic post of Chief Diplomatic Advisor. At the time, British intelligence officers had interpreted Pieck’s references to Vansittart as a code for his acquaintance with John King, attributing the deception as a clumsy method of confusing them. Yet, after the war, Pieck indicated that he looked forward to meeting Vansittart again, and it transpired that in May 1940, with the Germans about to invade Holland, Pieck had expressed an urgent desire to flee to England, where he expected his friends in high places to welcome him. This was bizarre – or very brazen – behavior from a Soviet spy who knew that the British authorities had rumbled him.

Yet when it came to bringing Pieck over, and interrogating him, the MI5 officers, led by Dick White, made no attempt to question him about the Vansittart connection – or, if they did, the redacted record conceals the fact. Certainly, the consequent report does not mention him. The oversight might seem simply careless, or an admission that the reference was jocular, and thus not worth pursuing. Other evidence, however, points to more complicated entanglements. In a Diary entry for January 5, 1945, Guy Liddell had written: “Kim [Philby] came to see me about xxxxxxx, who had been taken on in his section. Jane [Archer] when introduced to him recollected that he was one of the people who might possibly have been identical with the individual described by KREVITSKY [sic] as acting as a Soviet agent before the war, and as being employed in an important government office. [sentences redacted] Kim was very anxious to get at the old records of the KING case in order to satisfy himself that he was on sound ground. I have put him in touch with Roger.”

As can be seen, the identity of this possible recruit has been redacted. Yet, when publishing his selections from the Diaries in 2005, Nigel West very blandly, and without comment, inserted the name of ‘Colville Barclay’ in the place of the redacted name. In his 2014 biography of ‘Klop’ Ustinov (the father of Peter), Klop, Peter Day went further. He claimed that Barclay had come under suspicion by Jane Archer and Guy Liddell when they interrogated Krivitsky, as Barclay fitted the profile of the ‘Imperial Council’ spy as described by the defector – aristocratic, artistic, Scottish, and educated at Eton and Oxford. Unfortunately, Day does not provide a precise reference for this claim. In the published version of the MI5 Debriefing (edited by the scrupulous Gary Kern), which faithfully reproduces the text from the archival Krivitsky file, no mention of Barclay can be found. But we should be able to rely on Liddell’s gratuitous recalling of what Jane Archer told him about Barclay’s coming under suspicion.

So what has this to do with Vansittart? In 1931, Vansittart married Sarita, Barclay’s mother, who had recently been widowed. Thus Colville Barclay became Sir Robert’s stepson. Moreover, in another memorandum that did not make the final Krivitsky report, Jane Archer did allude to Sir Robert. As the interrogations progressed, Archer would send a daily summary to Vivian in SIS, and this correspondence can be seen at the National Archives in KV 2/804. In the item dated February 5, 1940, Archer wrote: “The C.I.D. case was the first discussed with Mr. Thomas [Krivitsky]. He said that the Soviet authorities had a great regard for Sir Robert Vansittart and followed his activities with great interest. None of the information regarding Sir Robert, however came through the source which furnished them with the C.I.D. documents. In further attempts to identify the person who procured the C. I. D. information Mr. Thomas was asked whether any mention had been made of this man being the stepson of some highly paced official. The word ‘step-son’ certainly aroused some memories in Mr. Thomas’s mind.”

This is all I have found. It does not offer anything conclusive about Barclay or Vansittart, but begs for some kind of follow-up. Why did the Soviets track Vansittart’s activities with such interest? If not the ‘Imperial Council’ spy, who was it who provided them with information? John Cairncross? Why was the stepson’ reference not pursued? (Was Krivitsky being devious again, confusing the issue of orphans, sons and stepsons?) Peter Day reports that Barclay did not know that he had become a suspect: he told Day in 2003 that he had never been questioned. One might have expected some reflection of this conversation to have appeared in Archer’s final report, but, either she felt that it was not so important, or her superiors instructed her to omit any such potentially embarrassing details.

Any closer inspection of this web of intrigue will of necessity require a plunge into the murky waters described by Kluiters above, and I am not yet ready to do this. It would not be surprising, however, to see a relationship between Pieck and Vansittart confirmed. Vansittart came from an originally Dutch family; he was a fierce anti-fascist (and might have mistaken the objectives of Pieck: Vansittart was equally opposed to communism); he maintained a private intelligence group, and he apparently received information from both Putlitz in the German Embassy (according to Norman Rose), as well as from Soviet agents (according to Charles Higham). Thus we should not discount the fact that Pieck may have played a very cagey game, and skillfully exploited Vansittart.

Be that as it may, if Pieck’s interrogators expected to hear more about the Imperial Council source when Pieck arrived for questioning, they were disappointed. Pieck confirmed that he had started to photograph documents at the Grosvenor Hotel in 1935, but then switched to use his apparatus at Buckingham Gate. He stated, however, that he had never controlled a second source at the Foreign Office, although he had heard of one from Krivitsky. “Krivitsky told him they could get the same material from another man at a tenth of the price”, the report ran, and went on: “Pieck was unable to throw any light on the other facts about a Foreign Office source which do not fit into the King case: – a burglary from the Foreign Office, the disused ‘kitchen’ in the Foreign Office alleged to have been used by an agent for photographing documents, and the renting of a special house. Pieck did not train King in photography, nor did he give him a Leica.” MI5 reluctantly concluded Pieck was telling the truth, but admitted they could not be sure until the Imperial Source were identified.

But the sleuths were getting closer. The VENONA transcripts had helped identify Klaus Fuchs, who was sentenced on March 1 to fourteen years’ imprisonment. Sonia had escaped to East Germany two days before. Since 1949, MI5 and the FBI had been whittling down the names of possibilities for the agent with the cryptonym HOMER, as revealed by VENONA, and in April 1951 they were able to point quite confidently to Donald Maclean, because of the visits he made from Washington to New York to visit his wife. The defection of Burgess and Maclean in May 1951 would give MI5 the name of the ‘Imperial Council’ source they had not very vigorously been pursuing since 1939.

A Missing File, and other Embarrasments

One of the last enigmas of the case is the destruction of the first volume of the John King archive. In this, one might have expected to find such items as the complete correspondence between Washington (Mallet) and the Foreign Office (Jebb) concerning the information that Levine was passing on. If you look up the files on John Herbert King at the National Archives (e.g. http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C11050136 ), you will find under both KV 2/815 & KV 2/816 a note that says ‘Vol 1 destroyed’. You will have to delve elsewhere to learn more. For example, in the Pieck files (KV 2/809-814), you can find at least three references to the destruction, which say, variously that the file was ‘destroyed’, ‘destroyed by fire’ and ‘destroyed by enemy action.’

While all three statements could be interpreted as communicating the same truth, this strikes me as more than a little suspicious. It seems to this particular observer that an enemy attack would have to be particularly selective to destroy completely just one of the King files, but leave the others completely unscathed. We do know that MI5’s offices at Wormwood Scrubs were bombed in September 1940, and several records burned, but the histories tell us that they had all been photographed beforehand, and that nothing was lost. Is it possible that this event could have been used as a convenient alibi for the removal of material that was potentially embarrassing?

The process of copying individual records into files to which they were related means that some of the items have been preserved, and one can tell from their Serial numbers that their source was the missing file. For instance, the interrogation of Oake, a colleague of King’s, that took place on September 26, 1939, receives the following handwritten comment: ‘(Original in PF 48713 KING, 50A Volume 1 destroyed in fire)’. Yet all such comments are made in the 1946-1947 time-frame: the Pieck records from 1941 never refer to the destruction of any files, by fire or any other agency. Unfortunately, the salvaged records that I have managed to identify and inspect do not offer anything spectacular: maybe another sleuth can come up with more dramatic examples.

One awkward fact that Jebb and the Foreign Office may have wanted suppressed was King’s connection with Mallet himself. Michael Serpell believed that some of the missing records could have referred to Special Branch’s search of King’s property. In a summary of the tripartite meeting with Inspector Rogers, John Marriott and him that took place on January 6, 1947 can be found the following astonishing statement: “Rogers handled King, and elicited his confession. He does not believe King told the whole truth and suggests King may have been shielding friends such as Quarry, Oake and Harvey. King claimed he left his wife because she became mistress of Victor Mallet who was until recently the British Ambassador to Spain (or maybe Mallet’s brother.)”

Victor Mallet was indeed the chargé d’affaires in Washington who had been dealing directly with Krivitsky’s agent, Isaac Don Levine, and communicating with Jebb, in September 1939. It is not clear where Serpell derived this fact of King’s wife’s affair, or when King actually admitted it, unless Rogers himself had just divulged it: it was not until March 7, 1947 that Serpell recorded an interview with the ailing King, who had just been released from prison. (During this interview, it was revealed that King’s son lodged in Pimlico, and that King himself had lived there during 1935-36! Pimlico – the district that Goronwy Rees mentioned!) Yet this disclosure, if it were in fact true, must have been highly embarrassing. Mallet would surely have had to own up to Jebb about the connection, as the truth would surely come out in any investigation, and it would presumably have damaged his career. (If he had a brother, he appears to have sunk without trace.) From Washington, however, Victor moved to Sweden as Envoy during the war, and was appointed Ambassador to Spain in 1946. He did not suffer.

Thus one can only speculate what else might have been lost in the destroyed file – including the source SIS report which Krivitsky saw, as detailed above. Certainly we are missing the full set of exchanges between Washington and London. It is thus impossible to build a reliable chronology of exactly who informed whom. One of the earliest accounts is actually Valentine Vivian himself, who wrote a report titled ‘Leakage from the Communications Department, Foreign Office’, dated October 30, 1939, which appears in full as the second King file, KV 2/816. Vivian is very open about the failure of SIS to take seriously the evidence of ‘Agent X’ (Hooper), who was treated ‘with coldness, even derision’ when he tried to pass on what Pieck had told him two years earlier, and had ‘remained forgotten, and in abeyance’ until Conrad Parlanti came forward on September 15, 1939. Vivian then reflects the current Foreign Office thinking (see below) when he dismisses Krivitsky – testimony that he would presumably have preferred buried when the defector came over a few months later. “We had, therefore, the bare word of KRIVITSKI – at the best a person of very doubtful genuineness and one, moreover, whose ability to speak on such a matter with authority was even more doubtful – to incriminate Captain J. H. King of the Communications Department, whose record appeared on the surface to be quite impeccable.” Peter Cook would have been quite proud of that performance.

Yet a strange anomaly appears. In his report, Vivian says that, after the identification of King was received on September 4, he was instructed to go on leave until September 25, but was to be kept under surveillance. Oake was interrogated on the 25th, and King the following day, after which King tripped up by visiting his mistress Helen Wilkie, and was thus charged the same day. But Alexander Cadogan, Permanent Under-Secretary in the Foreign Office, wrote – in an unpublished part of his diary dated September 15 – that King was currently being interrogated. Is it possible that, because of the Mallet connection, the Foreign Office decided to undertake its own investigation without informing MI5 or SIS? Or, perhaps Vivian did know about it, but was encouraged to portray another series of events, and to record it in some haste? Is the fact that Cadogan’s estate prohibited Professor Dilks from including this item in the published Diaries an indication of this subterfuge? (I have contacted Professor Dilks, but he can shed no light in the matter, as the sources I refer to were not available when he edited the Cadogan Diaries fifty years ago.)

Further indication that the Foreign Office was unduly embarrassed by the King affair was its determination to keep the conviction secret. Nothing appeared in the press, and Levine even stated, in November 1948, that the disgraced cypher clerk had been executed. (He had in fact been released by then.) It was not until 1956 that the British Government was forced to admit the whole account, after Levine offered the same testimony to a Senate investigation committee. The Foreign Office initially denied that there had even been a spy named King, but, when faced with the prospect of awkward questions in the House of Commons, then had to reveal that King had been tried under the Emergency Powers Regulations, and sentenced on October 18, 1939. One might understand the coyness as war approached, but the desire to cover up when the convict had already been released seems simply obtuse.

Lastly, how did the Foreign Office regard the evidence of Krivitsky? It was exposed to the first of the Saturday Evening Post articles in May 1939, and was immediately dismissive. Such comments as ‘mostly twaddle’, ‘Don’t want the rest’, ‘a few grains of sense in this rigmarole’, ‘General’s “revelations” not worth taking seriously”, are scattered among the hand-written annotations of the file as it gets passed around, including from the pen of the head of the Northern Department, Laurence Collier. The degree to which this official was clued into current events – and the responsibilities of his own section – is shown by a plaintive note he sent to Gladwyn Jebb on May 24: “Do we know anything about Genl. Krivitski?”. At the end of May, Collier rather reluctantly sent the cutting, with a letter, to the Embassy in Moscow, writing: “On the whole we do not consider that these would-be hair-raising revelations of Stalin’s alleged desire for a rapprochement with Germany etc. are worth taking seriously . . .”. Collier must have been a bit chastened to hear back from his colleagues in Moscow a few weeks later that the articles ‘have excited considerable interest’, and that ‘the consensus of opinion is that they may well be genuine’. He still opined that Krivitsky was ‘talking nonsense’ but agreed that Washington should be asked for the complete series, which arrived at the end of July. (He did not know that Jane Sissmore had had copies of the articles in her possession since they came out.)

What is extraordinary about this exchange is the apparent awareness in Moscow of German-Soviet negotiations, while London was still vaguely planning for a British agreement with the Soviets. The mission to forge such a compact, led by the improbably named Admiral the Hon. Sir Reginald Aylmer Ranfurly Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax, left from Tilbury on August 15, and was thus doomed from the start, whether Chamberlain was in earnest or not. (Marshal Voroshilov is said to have inquired of our gallant emissary: “You are not one of the Somerset Ernle-Erle-Draxes, by any chance?”) Collier and his minions continued to pooh-pooh the contributions of the Soviet defector, but then the record goes eerily silent. The next item recorded is not until November, two months after Ribbentrop and Molotov had signed the Nazi-Soviet Pact. On December 27, an official notes that ‘Stalin is expert at reconciling the apparently irreconcilable, as recent events have shown’, to which Collier adds that ‘he will find this particular reconciliation harder than most’. Collier would also survive to see the ‘Imperial Source’ unmasked, but I have not discovered any record of what his reaction was.

The Elusive Gallienne

And what of ‘Wilfrid de Gallienne’, the diplomat whom Andrew Boyle credited with the information about Krivitsky? The British consul in Tallinn, Estonia, during 1939 was indeed Wilfrid Gallienne (sic), and he was deeply involved in discussions about the protection of the borders of the Baltic States, including Estonia of course, in any future negotiations between the Soviet Union and Great Britain. His main claim to fame, however, appears to be the disagreement he had with a British lecturer in the Estonian capital, Ronald Seth, who was providing information to the Foreign Office while bypassing the local resident diplomat. In his reports to his superiors in London, Gallienne justifiably complained about this irregular back-channel, and admitted that he had had to rebuke the nosy academic. (For readers who want to learn more about the extraordinary adventures of Seth, who was later parachuted into Estonia as an ill-equipped SOE agent, but survived, I recommend Operation Blunderhead, a 2105 account by David Gordon Kirby.)

Yet, despite the imaginative endeavours of my researcher in London, I have not yet been able to find any minute or memorandum from Gallienne that touches on Krivitsky. My next step is to explore the Andrew Boyle archive, and, as I write this in mid-February, I am waiting to hear from the Cambridge University Library whether it can send me photographs of the relevant papers. Rather than starting with what are presumably voluminous documents that concern the creation of A Climate of Treason, I have made a more modest request to inspect Boyle’s correspondence with E. H. Cookridge, Malcolm Muggeridge and Isaiah Berlin, as I suspect these smaller packets may provide me with a glimpse of the way that Boyle nurtured his sources.

Cookridge is a fascinating case. He was born Edward Spiro, in Vienna in 1908, and knew Kim Philby well from the spy’s subversive work with communists there in 1934. His Third Man (1968) is thus a most useful guide to Philby’s early days. While claiming in his Preface to that book that he had access to secret sources (“Through my work in the Lobby of the House of Commons I had access to sources of information not available to the public”), it is clear that he was used by the government as a method of public relations as far back as 1947. He published in that year a book titled Secrets of the British Secret Service, in which he openly acknowledged the help that he had received from the War Office and the Foreign Office. One must therefore remain wary that, while being given access to certain documents, Cookridge would have been shown what the authorities wanted him to see.

His relevance lies in the attributions that Boyle grants him in his Notes to A Climate of Treason. Much of Boyle’s information comes from named sources, and most of them are actually identified, rather than being cloaked in the annoying garment of ‘confidentiality’. While I have not performed a cross-reference, I would hazard that most of the correspondence with these persons is to be found in the Boyle Archive, where individual letter-writers are clearly identified. Of this period, Boyle writes, for example (p 455, Note 15): “Confidential information to the author as attested in E. H. Cookridge’s notes from Guy Liddell of MI5.” One might react: What on earth was Liddell doing speaking to Cookridge? Did Cookridge (who died on January 1, 1979) ever publish an account of these confidences? Did Boyle consider, now that Liddell and Cookridge were both dead, that he could safely write about these secrets, or did he still fear the Wrath of White? I hope that a study of the correspondence with Cookridge will clear some of this up. If anyone reading this lives in the Cambridge area, and is interested in inspecting the Boyle papers in a more leisurely, more efficient and less expensive manner, I should be very grateful if he or she could get in touch with me. Similarly, I should love to hear from anyone who can shed light on the Gallienne puzzle.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, all this evidence does not bring us much closer to determining how and when MI5 and SIS might have learned more about the identity of the Imperial Council spy, and thus have been able to apprehend Maclean before he did any more damage. Yet the fruits of the research do show that Andrew Boyle’s claims may have some truth behind them, and that the assertions of the rascal Goronwy Rees may indeed have some substance. Moreover, the multiple anomalies in the archival record suggest that some persons had a vested interest in muddying the waters, and even using the written documents to start a bewildering paper-chase that might distract analysts from the real quarry. If one considers such events as the following:

- The reluctance of Krivitsky’s interrogators to apply pressure on him;

- Pieck’s enigmatic claim to have protectors at the Special Branch;

- Pieck’s professed desire to escape to England as the Nazis approached in May 1940;

- Pieck’s carelessness in confessing to Hooper his illicit activities in London;

- The reluctance of SIS to listen to anything that Hooper told them for two years;

- Vivian’s obvious discomfort and confusion about the facts of the King case;

- The contradictions in the chronology shown up by Vivian and Cadogan;

- King’s alarming claim about Mallet’s affair with his wife;

- The coyness of the British Government in admitting the facts about the King trial and sentencing;

- The barely credible account of a single King file being destroyed by enemy action;

- The apparent destruction of the copy of the SIS report that Krivitsky recognized during his interrogation by Jane Archer;

- Jane Archer’s uncharacteristically unprofessional and detached approach to the investigation;

- Pieck’s ability to re-enter Britain unnoticed after a watch had been put on him;

- The official historian’s laconic but undeveloped comment about Jack Hooper’s having worked for MI5, SIS, the Abwehr and the NKVD;

- The enigma of Pieck’s exact relationship with Sir Robert Vansittart;

- The failure to follow up on the clue of the stepson, Colville Barclay;

- The dogged efforts to try to put together a case that Pieck controlled the Imperial Council spy as well; and, overall,

- The remarkably unenergetic efforts, over a period of twelve years, of MI5, SIS and the Foreign Office to try to unveil an important spy in the corridors of power;

one does not have to be a rabid conspiracy theorist to conclude that there was another narrative being stifled that would tell a completely different story. If I were forced, before this programme of research were over, to identify one theory that might explain the anomalies in the story of Sonia, the Undetected Radios, and the Imperial Council spy, I would doubtless point to the delusional belief of Claude Dansey that his wiles, accompanied by the fearsome reputation of British Intelligence, could somehow control all the agents of hostile espionage organisations on this planet, and probably some on galaxies as yet undiscovered.

Thus we have a double Dutch Connection to be pursued: Jack Hooper, the half-Dutch disgraced SIS officer, who apparently worked for both the Abwehr and the NKVD, and is a pivotal figure in the Krivitsky-King-Maclean case; and Willem ter Braak, who has been claimed to be both a Nazi fanatic in the Abwehr, and a well-disguised NKVD spy. Could Claude Dansey possibly have been behind all this, pulling the strings? I shall have to put my best men and women on the job.

This month’s new Commonplace entire can be seen here.

Dear Tony,

FYI: https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/public/research-brought-halt-national-archives/

Dear Tony,

You write that “A Spy Named Orphan . . . is promoted as ‘the first full biography of one of the twentieth century’s most notorious spies . . .'” I have written to Norton, Philipps’s publisher, pointing out that this is not correct, as my biography of the Macleans was issued a year or two earlier. It is not indexed in Philipps’s book, but it is followed closely and cited once or twice. Norton claimed it was Philipps’s business. A friend of mine spoke to Philipps at his club (of course) and Philipps said it was not any of his business, that it was the publisher’s doing.

Thank you, Michael.

Fair point, but I was merely echoing what Norton claimed: it was ‘promoted’ as the first full biography. I was not endorsing that claim, but observing that I would have expected a measure of greater curiosity if Philipps indeed had that stature.

Anyway, I am glad your comment is added to the record. It does not make much sense to me for Philipps to distance himself from what his publisher decided to do. Is he backtracking from that position, I wonder?