[This report is the third instalment of my coverage of the rather prosaic figure of Roger Hollis, who surprisingly rose to become Director General of MI5. The first piece can be seen at https://coldspur.com/roger-hollis-in-wwii/ , and, in case you missed it, here is the link to the recent follow-up article posted on February 14: https://coldspur.com/special-bulletin-hollis-the-cpgb-in-wwii/, a Special Bulletin that adds an important account of Hollis’s handling of the CPGB during the war. This third chapter reveals the astonishing fact that, early in the Cold War, Hollis was deprived of his responsibilities for Soviet counter-espionage, while the poorly qualified officer who took them over resigned eight months later in protest at the leadership of Percy Sillitoe. During that time, however, Hollis was given a fresh chance by being sent to Australia to investigate security leakages. My investigation thus describes a critical – and puzzling – period in Hollis’s career while also uncovering a hitherto untold period of turbulence in the senior ranks of the Security Service. This is a B-class report.]

Contents:

Introduction

Hollis and Petrie

Gouzenko and the Aftermath

The Year of Transition – 1946

The Sillitoe Era: Hollis as B1, 1946-1947

Counter-Espionage: A 1947 Quartet

The November 1947 Reorganization

The Sillitoe Era: Hollis in 1948

Conclusions

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction

One might imagine that, when Victory in Europe was declared on May 8, 1945, MI5 might have started to re-organize for the fresh challenges of defending the realm against the Soviet Communist threat. In many eyes, the Cold War had started well before then, the most significant event being the Soviets’ abandonment of the Poles in Warsaw in August 1944. Certainly, the War Office was alive to the threat, and Guy Liddell had a few times remarked in his diaries that he expected Stalin to constitute a real menace when the war was over. The Foreign Office, however, was overall in its mood of ‘co-operation’ with the Soviet Union, believing naively that if they accommodated Stalin, he would reciprocate by drawing in his horns. MI5 was not taken in by that appeasing stance, yet no structural changes were made until Director General Petrie was replaced by Percy Sillitoe in May 1946 – and, even then, those were minor. What was going on?

In fact, MI5 had been downsizing for many months, with a large number of counter-intelligence personnel who had been attached to Army units in Germany in the second half of 1944 leaving the service and returning to more traditional civilian occupations. Its sluggishness in adapting to the Soviet threat – a torpor openly admitted by Liddell and Petrie before the war was over – can be attributed also to the fact that a high-level investigation into the future roles and structure of MI5 and MI6 had been carrying on for some months. It was undertaken by Findlater Stewart, the Chairman of the Home Defence Committee. It was not surprising that Petrie and Liddell held their horses if the outcome might have been that the two security services were to be combined. Moreover, Liddell’s second-in-command, Dick White, did not return from duty in Germany until mid-October, and his opinions had to be considered. When interviewed by Stewart, Liddell had rather generously indicated that he thought there could be efficiencies made in such an amalgamation. That opinion would have been gleefully welcomed by Liddell’s opposition number in MI6, Valentine Vivian, had he heard it, since MI6 considered itself the classier and more mature organization, and expected its senior officers to be in charge of any unified service. Dick White probably thought otherwise. Stewart’s report was not released until November 1945, however, and it recommended maintaining the status quo.

Another complication was the election of a Labour government, under Clement Attlee, in July 1945. While Attlee and his Foreign Minister, Ernest Bevin, were solidly anti-Communist, their party had a large pro-Soviet contingent, and the memories of working in partnership with Stalin to defeat Hitler were still very much alive. Indeed, there were senior members of Attlee’s Cabinet, and in the party at large, who made influential noises about the dismantling of free enterprise, and of Britain’s pluralist democracy. Thus MI5 had to tread lightly immediately after the war, until Stalin’s ruthless purges and executions in the countries that the Red Army had annexed started to influence popular opinion more strongly.

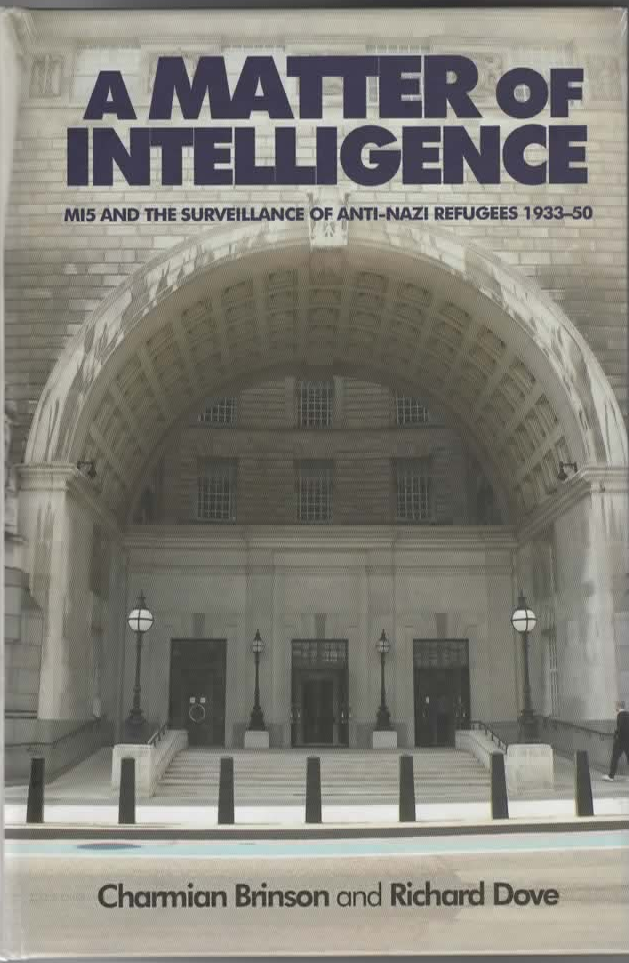

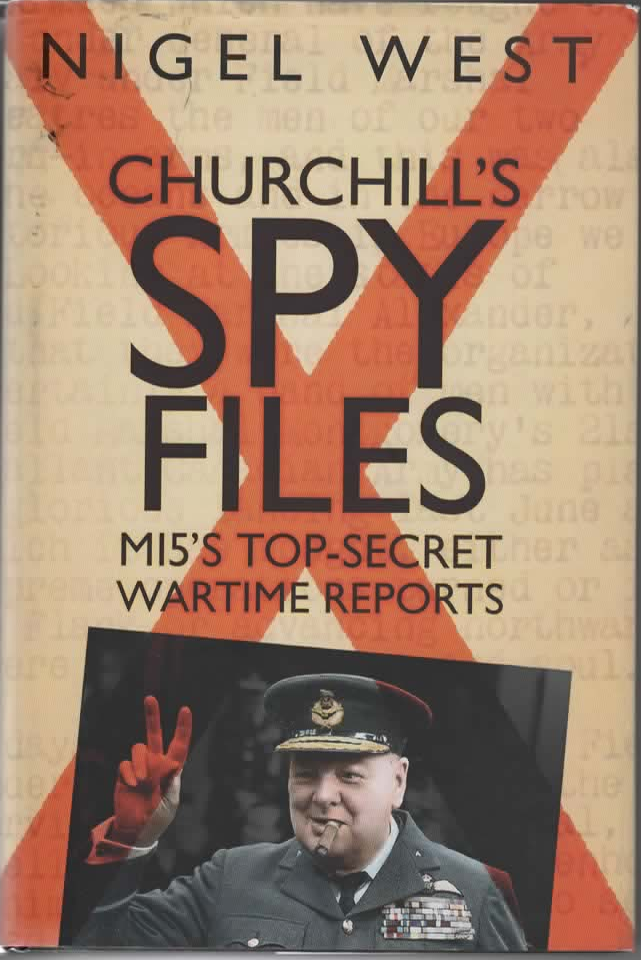

You will not find in Defend the Realm much of substance concerning MI5’s adaptations at this time. Christopher Andrew does not grant an entry in his Index to Findlater Stewart, but he offers two perfunctory paragraphs about the civil servant’s November report without analyzing the undercurrents behind it. He provides information (from the customary unidentifiable source) that the total MI5 personnel count in 1945 had dropped to 897 from its wartime peak of 1,271 in early 1943, and would fall further to 570 by 1947. But the authorized historian writes nothing about MI5 organization until he picks up Dick White’s ‘October Revolution’ of 1953 – an egregious lack of attention to the intervening eight years. Nigel West, in A Matter of Trust, his history of MI5 between 1945 and 1972, indicates that there was a changing of the guard after Sillitoe came on board, with the five divisions remaining intact. He presents White as replacing Liddell in the plum position of Director of B Division (with Liddell becoming deputy to the Director General), but he mistakenly has Hollis taking over C Division (Security) at that time, an appointment that did not take place until late 1948.

Hollis’s F Division was actually folded into B Division in 1946, with Hollis running B1, covering Communist and Fascist movements (the latter becoming a dying breed). Ewing, Mahoney and Moretta, in MI5, the Cold War, and the Rule of Law, characterize that move as a tactic responding to a need to withdraw from ‘the outright policing of communists and fellow-travellers’, something that Findlater Stewart had recommended in his ‘civil liberties’ lesson. Such ne’er-do-wells should not have their civil liberties removed, of course, but any open declarations of such seditious beliefs should have disqualified them from any government employment – a distinction that eluded Stewart. The essential fact was that Hollis retained his ownership of F Division for over a year after the war.

Hollis and Petrie

Even though he was head of a Division, Roger Hollis held the rank of ‘Assistant Director’ only. This was largely because his mentor and more experienced colleague, Dick White, also held that title, in B Division. White, who had performed creditably working for SHAEF as an intelligence adviser, and was promoted to Brigadier for his efforts, would have had his nose put out of joint if his protégé had enjoyed a superior rank in the Security Service. And, by summer 1945, as I described in my first piece, Hollis must have felt somewhat isolated, and his job at risk. He was not leading a happy team. He had disparaged Hugh Shillito, John Marriott had voiced to Liddell his frustrations about working under him, and Milicent Bagot had requested a transfer. In fact, Nigel West claimed that Bagot, ‘the veteran anti-communist’, worked as E1 under Kenneth Younger at the end of the war, so Hollis may have lost his invaluable source of expertise in, and knowledge of, the international communist threat.

Not that his reduced status appeared to harm Hollis’s relations with Petrie, who trusted his judgment. Christopher Andrew wrote (p 282) as follows: “In the final stages of the war Petrie had a series of meetings with Hollis to discuss the post-war threat from Soviet espionage”, this time sourcing his remarks to a real file, KV 4/251 ((which covers the topic of Communists in government in the train of the Springhall espionage case). I had referred to this file in my first report on Hollis: little took place in the first six months of 1945, but matters did pick up in the summer. On July 12, John Marriott (F2A) submitted a rather ponderous report on Communists in sensitive government departments. He provided a list of seven key establishments, and, rather shockingly, indicated that there were no less than eighty-four known CP members installed at R.A.E. Farnborough. Hollis moved cautiously, seeking agreement on action to be taken from other Divisional heads, and suggesting the use of existing ‘machinery’ (i.e. the Joint Intelligence Committee, and Sir Herbert Creedy’s new Inter-Departmental Security Committee) before raising his head above the parapet.

In contrast to what Andrew wrote (and there is, incidentally, little evidence of meetings between Petrie and Hollis, but only of memoranda being sent, and Petrie’s hand-written comments being recorded), the espionage threat is not explicitly called out. Concerns about the return to their native countries of foreigners who had been legitimately employed during the war, and having had legal access to confidential information, are voiced. The listing of CP members (who must presumably have been quite open about their affiliations) reflects the fact that Communists in principle owed their loyalty to another institution or regime, although the evidence does not indicate a belief that such persons had been planted by the Soviet Union. The problem was that they had been legitimately hired, and that firing them would be politically dangerous. Efforts could be made to vet candidates in the future, but that would also face roadblocks.

And then the events of September 1945 (see below) caused Hollis to sharpen his stance radically. On September 6, Petrie had written a short memorandum endorsing Hollis’s approach, indicating that the Cabinet should have to approve any action. After an overture to Menzies in MI6 was made, in order to gain further reinforcement, Petrie added a handwritten note on September 17 that confirmed Hollis’s recent statement made ‘before he left for the USA’ on September 15. Petrie may have presented Hollis’s destination as the USA intentionally: Hollis, who had returned from holiday on September 14, flew to Montreal via New York for reasons of security. He departed on September 15 to consult with the Canadian authorities on the fall-out from the Gouzenko affair, and from the latter’s identification of Nunn May as a Soviet spy.

Yet, in a diary entry for February 4, 1946, Liddell noted that Hollis had been to the USA in the recent past, to liaise with the FBI. The previous August, Hoover of the FBI had invited Hollis over, specifically and repeatedly, an overture that rankled Menzies and Vivian in MI6. As late as September 3, Liddell reported that Petrie, under pressure, had not yet accepted Hoover’s invitation to Hollis. By mid-month, however, Liddell knew that Hollis would manage to fit in a visit to Washington on his return from Canada, and that his selection for representing MI5 in Ottawa was a convenient assignation. Liddell’s coyness about it at the time may have been adopted as a way of misleading Philby.

Gouzenko and the Aftermath

I have written extensively about the defection of Igor Gouzenko, and the manner in which Hollis’s role has been distorted and misrepresented by a number of authors who have either been careless in their research (with particular negligence over chronology and geography), or have had an ulterior motive in crippling Hollis with devious schemes to conceal his own guilt as a Soviet mole, or his assumed identity of ‘ELLI’. ELLI was the mysterious agent described by Gouzenko, and determining the name behind the cryptonym very much occupied Liddell and others in the following weeks. The dedicated reader may want to turn to https://coldspur.com/on-philby-gouzenko-and-elli/, and https://coldspur.com/who-framed-roger-hollis/. I summarize here my key findings from those reports, while amending them to some degree in the light of subsequent research.

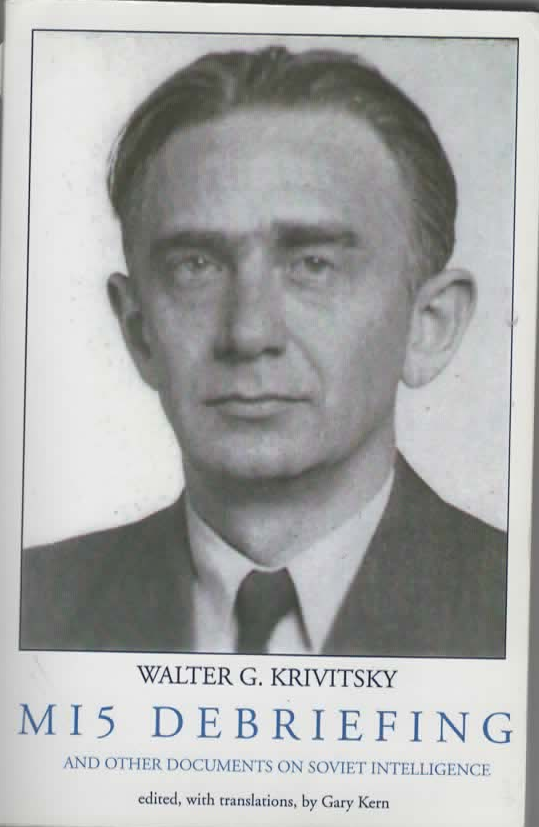

I pointed out then that MI5 had acted very sluggishly in letting MI6 (in the person of Philby) take control of the case, when it was the responsibility of MI5 to handle such matters in the Dominions. Philby had recommended that Hollis be sent out, but, contrary to what Chapman Pincher, Amy Knight and others wrote, Hollis’s mission was to handle the high-level political implications of the actions of Nunn May, who had been unmasked by Gouzenko, not to interrogate Gouzenko himself. I suggested then that, if an interrogation of Gouzenko had been sought, the team of Jane Archer and Stephen Alley should have been sent out to reprise their success with Krivitsky. I indicated that no disciplined interrogation of Gouzenko took place, and, in any event, Hollis did not meet him until the end of November.

On reflection, I judge that it would have been of little use sending out Archer, either. Gouzenko would not have provided many insights into Soviet spy tradecraft (two years later, Alan Foote would suggest that he did not understand the structure of GRU cells at all), but he was knowledgeable about ciphers and codes, and the Americans were able to take advantage of his expertise. Frank Rowlett, of the ASA’s Operations Division, led the project to interrogate Gouzenko. Rowlett arrived in Canada on September 25, and, accompanied by a Canadian Sigint officer (Gilbert Robinson) and an RCMP inspector (Leopold), was taken to Gouzenko’s refuge ninety miles from Ottawa. Significantly – and rather scandalously – no officer from GC&CS was invited to attend. (In Code Warriors, Stephen Budiansky, relying largely on the Benson/Phillips history of VENONA, writes that ‘in response to a prompt entreaty by the British the Canadians allowed an American expert on ‘crypto matters’ to come an interview the Soviet defector’, but his assertion is unsourced. The requester was probably the Canadian head of British Security Coordination, William Stephenson, since in his diary entry for September 25 Guy Liddell complains bitterly about Stephenson’s interfering in the case.)

It is worth describing in more detail the circumstances in which Hollis was hurriedly sent out. Philby suddenly was occupied by the Volkov business – the alarm of the would-be Soviet defector in Turkey. He may not have wanted to send out his assistant, Jane Archer, as she was too sharp. He therefore recommended Hollis to Liddell, in the knowledge that Hollis would not be so incisive. Yet Liddell took a superficially thoughtless attitude towards the notion of responsibility, being slow to point out that Canada came under MI5’s bailiwick. Moreover, the Canadians might have been shocked if a woman were sent over for such a delicate task. Yet, considering that the goal of the visit was not to assist in the interrogation of Gouzenko, but to discuss the implications of the case at a high level, Guy Liddell or Dick White would have been a better choice. White was, however, still in Germany, and did not return until mid-October. Thus B Division could not have been left without its Director and Assistant Director.

On September 14, Liddell recorded in his diary: “Kim has pressed SIS to let Roger go out and take charge of the case and this has been agreed. Roger is coming up today from leave.” Before Roger returned, however, Liddell displayed further incompetence by suggesting that Herbert Hart go out for a week to ten days while Hollis finished his holiday (an observation that suggests Hollis was breaking his leave to be briefed: he must have been holidaying locally, in Broadstairs, say, rather than Barcelona or the Bahamas). The group concluded, however, that ‘as we were committed to sending an expert on Soviet espionage Roger ought to go’. Little did they know how meagre Hollis’s expertise in Soviet espionage was. In any event, Gouzenko had by then been whisked away to a secure location, and would soon be interrogated by Rowlett. Moreover, Hollis arrived in Montreal the same day (September 17) on which Nunn May arrived back in Great Britain. Liddell would have to handle the management of May with Hollis largely offering guidance from afar. His second visit lasted from October 22 to the end of November, a mission in which he was trying to encourage the Canadian government to move with more urgency on the lessons from Gouzenko.

For the record, Chapman Pincher’s coverage of the events is a typical mix of invention and speculation, lecturing his readers on what Hollis should have done in response to the Gouzenko affair. Typical is his citation of a declassified letter ‘which he dictated and signed in his tiny handwriting on September 10, 1945, when he may have been beset by fear and the need for evasive action’. It was (according to Pincher) despatched from Blenheim to the Foreign Office. Yet Hollis was on leave that week, and he knew nothing about the news from Canada. Pincher even points to Hollis’s possible furtive consultation with Philby at this time, and also cites Hollis’s ‘gratuitous letter and facile report’ to the Foreign Office about the views of German Communists in Britain (unidentified and undated, of course) as evidence that he was not taking the revelations about May seriously.

As I described above, on his return, Hollis drew attention to the Gouzenko affair – and the guilt of Nunn May, in particular – in order to strengthen his case for banning leftist scientists from key positions that offered access to confidential information. He was thus heavily involved with the fall-out from the case. In fact, 1946 can be seen as a year when three threads involving Hollis came to be woven together, in an outcome that may have surprised him: i) the continuation of his project to protect government institutions from possibly unreliable Communist elements within them; ii) the pursuit of the May case, and the need to bolster MI5’s Soviet counter-espionage efforts; and iii) the re-organization of MI5 under Sillitoe.

The Year of Transition – 1946

On the first thread, the archival record is somewhat bare for 1946, but the documents from KV 4/251 can be complemented by observations from Liddell’s diaries. In March 1946, after an inquiry from Group Captain Peter Paynter in the Air Ministry concerning Civil Service policy on Communists, Group Captain J. O. Archer, D3 (Jane’s husband) drew Hollis’s attention to the increasing problem, and saw Paynter’s communication as a way of seizing the initiative. Consequently, Hollis wrote a paper that highlighted how the danger had increased during the war, but that the terms of engagement had shifted from possible ‘political strikes and even to revolutionary outbreaks’ to a more subtle hazard. “The higher social status of the present membership has brought a new danger to the fore as the scientists and professional workers, who are now in the Party ranks, have access to far more secret information than had the pre-war membership.” He outlined in particular possible subversion in the Royal Air Force, and indications of leakage, but his whole focus was on Party members, not on a more clandestine cadre.

It was in fact the Foreign Office’s Harold Caccia (then chairman of the JIC Sub-Committee) who raised the bar by seeking Hollis’s opinions, in a memorandum of May 11, 1946, that merits quotation in full:

Another question that occurs to me is the lessons to be learnt about the steps which the Russians are likely to take to penetrate our own governmental organisations, particularly the Foreign Service. From the report it looks as if the Foreign Service ought to be particularly on their guard against any members or ex-members of the Party and against ‘drawing room’ Communists. But is this a fair deduction and are there others that affect our security?

This was a very shrewd observation from Caccia, and it is difficult to determine what prompted his suspicion that there might be ‘Enemies Within’ (pace Richard Davenport-Hines). Was it his attendance at Trinity College, Cambridge, and his familiarity with such as Maclean and Talbot de Malahide? Hollis rose partially to the bait, but not with obvious conviction about the opportunity, rather weakly just asking Caccia to provide particulars if any such cases occurred. A more imaginative officer would have arranged a meeting to gain deeper insights into how Caccia had arrived at his concerns. An important file on ‘Communists in the FO’ appears to be open at this time, Y Box 5925. And that is the last entry in the file for Hollis as AD/F.

The fact that Hollis was occupied with traditional duties is shown by an entry that Liddell made in his diary for February 19, 1946, when Hollis was reporting to the Director General’s meeting the status of a Cabinet Committee still investigating Fascism. An intriguing note from May 10 indicates that Liddell was accompanied by Hollis when he attended a JIC meeting to discuss ‘Russian sources’. This was followed by the cryptic observation that:

A number of other suggestions have been made and the JIB are to set up a committee to discuss the availability to press material [sic]. A decision was also reached about periodic reviews and appreciations of Russian activity.

These annotations may have been deliberately elliptical, although comments that Liddell later inserted that day indicate that the discussion may have been due to incidences of leakages from the Cabinet and from the Ministry of Supply. Liddell seemed keen to follow these important matters up, but was receiving cautionary sounds from Prime Minister Attlee, who demanded strict observance of ‘defence of the realm’ constraints, and seemed very nervous about suspects’ names appearing anywhere. (This was still early in Attlee’s administration, and he always had an eye on his left wing.)

On May 28, Hollis pressed for more extensive vetting of short-term Service officers. Liddell and Hollis discussed intelligence relating to atomic energy, again showing how the May case was starting to blend with traditional security concerns. Liddell wanted all factories producing relevant equipment to keep MI5 informed: Hollis agreed in principle, but was reluctant to intervene until they ‘had eliminated Brock, who could only think in terms of barbed wire and fences’. Who Brock was, I do not know, but this sounds like a recurrent security theme over the ages, like locking PCs in place when information could be smuggled out on thumb drives. The last significant item from this era comes from July 22, when Liddell defended Hollis in a discussion with the Director General (now Sillitoe) over vetting. Apparently Hollis was in a dispute with one Adam, who had a fogeyish and sadistic approach to vetting. (This was probably Lt. Col. Adam, who had been responsible, as D4, for port security during the war.) Liddell touted Hollis’s abilities as the only person really qualified to express an opinion as to whether a Communist should be employed or not, since he ‘had been responsible for making a file on the individual and knew precisely how to evaluate the documents’. To my jaundiced eye, that policy seems remarkably indulgent, and it is clear from the archives that Hollis did not want to insert himself in such a procedure, and to assume that important responsibility. One might counter that, if a man or woman was an avowed communist, he or she had no business being employed by any government department. But this was the Attlee age, and well before Burgess and Maclean.

The second thread, namely the fallout from the May case, and the assessment of the state of MI5’s Soviet counter-intelligence, can be detected primarily from Liddell’s diaries. (For a breakdown of the way that May was arrested and then confessed, see Andrew, pp 342-348. The authorized historian also covers Hollis’s spirited response to Philby’s interference, which I also wrote about in my earlier article.) The fact is that the May case was receiving close attention at a level higher than Hollis. On October 1, 1945, Liddell held a meeting with Akers, Cockcroft, Hollis (in between his visits to the Americas), Marriott and Rothschild to discuss it. They went over the ramifications of May’s bringing back documents from Canada to which he was not entitled, and even considered possibilities for deception, namely planting documents on May, a project that Akers and Cockcroft quickly deflated. The next day Hollis showed his serious intentions, at a time when the Canadians were weakly considering appeasing the Soviets, by showing Liddell a draft telegram ‘which he wishes the F.O. to send to Halifax and Macdonald dispelling certain doubts which seem to exit in the minds at any rate of the Canadians that a show-down with the Russians is likely to cause serious damage to political relations’. Liddell supported Hollis’s stance, as he judged that a failure to strike hard could ‘only cause a loss of prestige in Russian eyes’. Whether that telegram was despatched is not clear.

Despite Hollis’s more aggressive inclinations at this time, he was apparently not entirely top candidate for taking over Soviet counter-espionage. In a weird note from October 12, Liddell reports on a dinner he had with Dick Brooman-White, asking him whether he would agree to return to the fold. (Brooman-White had transferred from MI5 to MI6 in 1943, had been beaten as a Conservative candidate in the general election of 1945, but would go on to win the seat of Rutherglen in 1951. A contemporary of Philby at Trinity College, Cambridge, Brooman-White gained some notoriety by defending Philby in the Marcus Lipton affair of 1955.) “I had in mind that he might perhaps do something towards getting Soviet counter-espionage on its feet,” Liddell wrote. Apart from the fact that, if that function were indeed prostrate, Liddell was as responsible as anyone, the admission revealed Liddell’s ultimate lack of confidence in Hollis. Everything that Liddell writes thereafter about Hollis’s ‘indispensability’ in B1 should be treated sceptically. Brooman-White showed interest, but indicated that he wanted to work abroad.

Liddell was not helped in his cause by the timid stance taken by the outgoing Petrie. He took Hollis with him to a meeting with the Director General on October 18, as he judged that progress on the Canadian business was being thwarted by a lack of decision-making at the top. Petrie did not want to see Attlee over the matter, and suggested that the pair should meet with Menzies, with a view to the latter going to the Prime Minister. That was pusillanimous. Apparently, Menzies quickly agreed to see Liddell and Edward Bridges (Head of the Home Civil Service), and he committed to taking Hollis with him to the meeting. I do not know whether it ever took place, and, if it did, whether its outcome has ever been recorded, but four days later Hollis was steaming out of Southampton on the S.S. Queen Elizabeth on his way to Halifax. On October 30, Liddell reported sending a message to Hollis, reflecting some frustration at the Canadians’ continued refusal to take any action.

Liddell’s relevant entry for November 9 is worth quoting in full:

Marriott showed me a telegram from Roger saying that if the Canadians went off the deep end on the CORBY [= Gouzenko] case he thought we should do something about MAY on the grounds that if the latter had not already gone completely to ground he certainly would on hearing the arrests in Canada. Moreover, the Canadians might not think that we were playing our part. Roger is to meet the PM, the President and Mackenzie King in Washington, if required. They will be having a discussion on the whole case, after they have settled the little matter of the atomic bomb, and its handing over to the Russians or to the Security Council.

This points me to a couple of conclusions: i) One advantage of the Canadians’ dilatoriness was that it gave the British a chance to catch May in the act. As the Gouzenko archives show, Hollis was most insistent that plans should proceed to entrap, but the quarry failed to turn up for a rendezvous. He had obviously been warned. ii) Hollis was held in quite high esteem if he was authorized to parley with the three countries’ political heads, and his visit to Washington obviously gave him cover to meet Hoover.

The project for establishing the new counter-espionage order plodded on. On November 30, Liddell had a meeting with White and Hollis to discuss the formation of ‘a Russian section’. “Roger is now convinced of the necessity of this”, he wrote (reflecting Hollis’s revival in the light of the Gouzenko/Nunn May business). What is suggested is a nucleus of John Marriott and Michael Serpell, with Hollis’s role left inexplicit. Yet it still requires Petrie’s approval. Liddell adds that he has in mind also Hill of B.1c and Skardon, but that their participation is problematical for a variety of reasons: Hill owned a private business, and there were complications over Skardon’s pension with Special Branch. There is no mention of Milicent Bagot. Strangely, Petrie still seemed to want to put his imprint on the structure, even though he was shortly to retire. He wanted to keep Soviet counter-espionage in F Division, but he accepted that Marriott and Serpell would constitute the nucleus. And then the uncertainty over Canada’s timorousness over the Gouzenko affair was blown when Drew Pearson, a newspaper columnist in the USA, drew attention to the events in February 1946. Liddell characterized Pearson as ‘bitterly anti-British’, although his outburst may have helped the UK government in its prosecution of Nunn May. Liddell had a meeting with Hollis, Burt, Cussen and Sinclair over the legal implications, and whether May was still subject to the Official Secrets Act.

At this stage, the third thread (the reorganization) dominated. In fact, Sillitoe had little to do with it, although he had been lurking in the wings since December 1945. Liddell had learned about Sillitoe’s appointment by the worst possible method, on December 17, when Desmond Orr, having heard the strong rumour, leaked it to him. Liddell went to see Petrie, who gave him a lame excuse as to why he had not been appointed, and Liddell catalogued in his diary the several reasons why appointing a policeman to head the Security Service were ill-advised and demoralizing. Petrie’s cowardice is shown by the final sentences of Liddell’s entry for that day:

I asked him [Petrie] whether he was going to tell the office. He said no, he thought it would be better if it leaked out gradually. I asked if he had any objection to my telling a few senior members working under me. To this he rather reluctantly assented. Personally I cannot see the point of not informing the office, who have got to know sooner or later and may feel somewhat insulted. DG I gather had said that he would not stay later than 10th March but at Shillito’s [sic!] request he is now staying on until April. This is unfortunate since for 3 months he will be filling Shillito up with all the wrong ideas.

Findlater Stewart had wanted Petrie to hang on for a couple of years. Yet his enduring even a few months caused tensions.

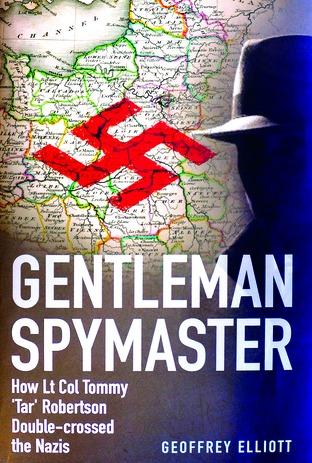

The initial feedback on Sillitoe was not good, from Curry, from Hart, from Burt, from ‘Tar’ Robertson, and from others. Liddell discussed the appointment with Menzies on December 31: there might have been some Schadenfreude in Menzies’s sentiments. He saw the appointment as a downgrading of MI5, and declared that the move was undesirable in giving it a police stamp. Menzies said that he had declined an invitation to appear on the selection board for the post, and he gave Liddell a little lecture on what measures had contributed to his own survival. Thereafter, Liddell and his crew had to buckle under Petrie’s determination to leave his mark. Liddell had been having deep discussions with Dick White about re-organization ever since the latter’s return from Germany. Even then, White’s promotion to head of B Division, if Liddell became either DG or DG’s deputy, was not a done deal. Curry was still anxious to take over. On January 8, Petrie asked Liddell to ‘consider the future of Russian espionage’ (an odd way of describing the matter).

Petrie introduced Liddell to Sillitoe on February 8, and four days later Petrie expressed his strong objection to the amalgamation of E and F Divisions into B, which is what had been worked out by Liddell, Hollis, White and Horrocks. “So far he has only seen Horrocks and Charles on the subject”, Liddell wrote. “They had a sticky passage and the question is at the moment in abeyance.” ‘Tar’ Robertson was one of the most vociferous critics of the Sillitoe appointment, and eventually resigned over it: Liddell was trying to find him a prominent role in B Division. Petrie climbed down a bit on February 27, at a time when Liddell was earnestly trying to build some bond with Sillitoe. As Liddell wrote:

The D.G. held a meeting to discuss B. Division and its amalgamation with E. He has approved of the charts. He raised the question of F Division and was still hankering after putting Russian espionage into B. and leaving the rest of F. where it is. We all said that this was a bad idea and he decided for the time being therefore to leave Russian espionage where it is.

That is an odd observation, since, as recently as November, Petrie had expressed a desire to see ‘Russian espionage’ remain in F Division. Liddell did not seem to notice the inconsistencies.

That very same night, Liddell left for a tour of the USA and Canada, not returning to the office until April 25. He found that White had in the interim been busy shaping the new B Division. Sillitoe was now ready to move in; MI5 would henceforth report directly to the Prime Minister, and Sillitoe would have audiences with Attlee every fortnight. Jasper Harker (still Deputy DG) had been given a reprieve until September, when he was definitely going to leave – a departure that, in my opinion, might well have opened up the possibility of Jane Archer’s returning to the fold. It was Petrie who now told Liddell that he would succeed Harker as Deputy Director General in September. Liddell judged that Petrie was being apologetic, and the diarist recorded that he was afraid the job would turn into a backwater. He determined to discuss the matter with Sillitoe, who officially took up his post on May 1.

The reorganization debated dragged on. Liddell had a long talk with Sillitoe on May 23, observing: “As far as amalgamation of B and F were [sic] concerned the matter was simple. All that was necessary was to call F Division B.1.” A further discussion was held on May 27, Liddell acknowledging that the amalgamation could be effected more profitably when F Division was housed in the same building as B, Hollis strongly supporting the motion. For the purists, Liddell noted: “It was left for consideration whether F.3 should go into B.2 and whether B.1. should also go into B.2. F.2 would then become B1.” F3 was the section that monitored Fascists and other dubious groups like the Peace Pledge Union and Jehovah’s Witnesses: it was wisely left alone. In the event, B1 and B2 would remain separate for a year or so, with B2 continuing to watch espionage from non-Soviet sources. Yet still no firm decision was made: presumably everyone was waiting for Harker to retire. Liddell could not move into the Deputy DG’s office, and hand over his B Division leadership to White, until Harker was out of the picture.

I should point out that this potentially represented a critical career move for Hollis, and change in status. As head of F Division, he was nominally a ‘Director’, but held the position of ‘Assistant Director’, as explained above. Moving his Division under White, as the incoming B Division Director, would have constituted some sort of demotion. Moreover, Liddell was pressing to eliminate some of the titles in currency, including that of Assistant Director. What Hollis thought about all this is unknowable, but the diffidence he showed earlier about grasping the reins may be attributable to such considerations.

In any event, Hollis expressed his frustration at a DG meeting on June 11, although his complaints seemed to be more with MI6 than the sluggishness within MI5. He had attended a JIC meeting, where the JIC had requested a report on Communist activities throughout the world. As Liddell wrote in his diary:

He did not know who according to the present charter was really responsible. SIS had written a certain amount but Hollis thought that much of it was rather off centre and that many of the old fallacies about the Soviet Govt. and the Comintern were creeping back. Jane Archer had rather let herself go on her old theories and had not included in her note any reference to the very important conference of C.P.s which had taken place in Prague. This conference was really a reconstitution of the Comintern Conference except that those present were confined to representatives of countries within the Soviet sphere of influence. Jane said that she had not seen this report. I said that, in my view, we were, in accordance with the charter, really responsible for the overall preparation of the report. Hollis said that SIS seemed to take a different view. The net result was likely to be a bad report.

I find this a fascinating gobbet. It shows that Hollis was meeting regularly with Jane Archer, but was trying to take a leading role, trying to show a realistically more hawkish stance than his previous mentor, but still determinedly focusing on the Comintern, and what replaced it. Why the conference in Prague was ‘important’ was not stated, nor was it clear what Jane’s ‘old theories’ were. (What were those ‘old fallacies’?) It is possible, but unlikely, that she had been unduly influenced by her boss, Kim Philby, in MI6. I normally associate her with strong suspicions about the true motivations and machinations of Stalin and his gang, and the person who took a firm lead in comparison with her less forceful male colleagues. Maybe she had simply, but correctly, dismissed the importance of Comintern-like conferences, and her ‘old ideas’ were related to Krivitskian insights into subversion, notions that Hollis was reluctant to assimilate.

Sillitoe obviously had to approve the reorganization, but he was taking time getting up to speed. He held a meeting to discuss it on August 6. Nothing much happened, except that Sillitoe wanted Liddell to give Curry the offer of B2. Liddell undertook to do this, although Curry had already told him that he could never work under White. On August 12, however, he told Liddell that he would accept it, but he seemed depressed. And then, on September 16, Liddell reported that the new organization had been made official, with his own position as DDG clearly defined. F Division was amalgamated with B Division, and Roger Hollis was now head of B1, and responsible for all Soviet counter-espionage.

The Sillitoe Era: Hollis as B1, 1946-1947

Hollis’s term did not start auspiciously. At the end of June, Klaus Fuchs had returned to Britain to take up a position as head of the Theoretical Division at AERE Harwell. In August, Henry Arnold joined the establishment as Security Officer, and he immediately contacted MI5 with concerns about Fuchs. The investigation into Fuchs’s loyalties lasted for over a year: the story has been told in many places. I covered it in Chapter 9 of Misdefending the Realm; Mike Rossiter, with a scientific bent, tackles it in Chapters 14, 15, 16 and 17 of The Spy Who Changed the World; the atomic expert Frank Close has an excellent account in Trinity, where he also dives into some of the social shenanigans at Harwell; Chapman Pincher even gets many of the facts right in Treachery, in Chapter 34. Both Rossiter and Pincher misidentify ‘J. O. Archer’ as ‘Jane Archer’, and Pincher is predictably severe on Hollis’s role, when in fact the process constituted a typical MI5 bureaucratic muddle.

I recapitulate the brief highlights of the case. After Fuchs took the opportunity to inform Arnold of his planned movements – not an action that had been requested – Arnold, taken aback by his behaviour, contacted J. A. Collard (an officer in C2, part of Security and Vetting) in early October, informing him that Fuchs was engaged on Atomic Energy work of extreme importance. In turn, Collard sought clarification from B1C (Russian and Communist Espionage and Information) and from B4 (the operational support group then being run by ‘Tar’ Robertson). Robertson, addressing B1C (Serpell), seemed a bit surprised that Fuchs already had a Personal File created for him. He had assumed that Fuchs had been vetted. At the same time, Serpell raised the alarm that Fuchs might be passing information to the Russians, simultaneously bringing in B1A (Left Wing Subversion) into the discussion. All this prompted Serpell to write a long memorandum in mid-November, explaining how circumstances had changed, and reminding his readers of Fuchs’s communist past, especially of his association with the dangerous Hans Kahle. He also raised the possibility that Rudolf Peierls, a close friend of Fuchs, might be equally dangerous.

On November 19, Hollis wrote a brief note, as follows: “I consider that present action should be limited to warning W/C [Wing-Commander] Arnold about the background of Fuchs and Peierls. We should ask him for a report in due course.” This was a weak response. Peierls did not work at Harwell (as Collard immediately pointed out), and Hollis’s meek reaction went against the grain of his recent more vigorous efforts to root out Communists in other government positions. Now John (‘Jo’) Archer got into the act, also in C2, and wrote to his boss, J. M. Allen, making an urgent appeal that both Peierls and Fuchs should be divorced from any work on atomic energy. Allen was cautious in his response, recognizing the considerable differences of opinion, and wanting to reach ‘a balanced view’.

Meanwhile, Hollis had asked his right-hand man Graham Mitchell (B1A) to verify that the Claus [sic] Fuchs being discussed was the same man who had been interned in Canada in 1940 – a quite remarkable show of ignorance by the officer who was supposed to be the expert in these matters. Mitchell investigated, confirmed that the two were the same, and volunteered the information that Fuchs had been one of the first to be sent back from internment in Canada in January 1941. Hollis’s response of December 4 was again weak: given how tough he had appeared over Nunn May earlier in the year, his assessment was inconsistent, at least. He acknowledged the facts, but saw nothing ominous. “I myself can see nothing on this file which persuades me that FUCHS is in any way likely to be engaged in espionage or that he is any more than anti-Nazi.” He went on to conclude:

If Lord Portal wishes to exclude people with records such as those of FUCHS and PEIERLS, we must, I suppose, lend our assistance, but I think he should be advised that it will lead to a very considerable purge which will presumably have to include a number of very highly placed scientists.

And that was, of course, the nub: a ‘Purge Procedure’, which definitely should have happened then. Hollis laid it out in black and white that he was not in favour of it, and would only reluctantly contribute to the project.

Yet Liddell was similarly wishy-washy, recording his agreement with Hollis’s judgment on December 12. He recapitulated the case against Fuchs (and that against Peierls, which seemed to be based purely on the facts that he had a Russian wife, and had visited the Soviet Union in 1937), and he brought White into the chain:

On the other hand, I do feel that there is a prima facie case for investigation, and that where such important issues are at stake we cannot possibly afford to leave matters as they are. I think it would be unwise to make any approach to the Ministry of Supply until we know more about these people.

All that White said as a rejoinder was that the case should be considered by B1A (Left Wing Subversion) rather than B1B (Russian and Communist Espionage Investigation), which seems a bizarre and petty observation, by any standard. Was White not in charge? Had he not made the missions of his groups clear? Was there really an important distinction between the two, and did White and his crew really know how to distinguish origins and precise motivations from threats who might not play with a straight bat?

The outcome was that Hollis applied for Home Office Warrants on Fuchs and Peierls on January 1, 1947, so that their mail and telephone calls could be intercepted, and Mitchell duly executed the request on January 18. Yet their dawdling for several months assumed that nothing was happening in the meantime. At the time, however, Fuchs was desperately trying to make contact with his old Party friends, but was thwarted by the fact that some instructions for assignations were wrong, or people he sought out (e.g. Jürgen Kuczyski) could no longer help him. (SONIA’s brother was in trouble with the CPGB.) It took Fuchs until July 1947 before he made contact with Hannah Klopstech, and he then had his critical encounter with Feklisov on September 27. By then the surveillance had been called off by Mitchell, on April 4, 1947. Fuchs’s correspondence had not revealed anything subversive: the project had never involved tracking his physical movements. Archer agreed with the stop notice. On May 22, Liddell approved the cancellation of the Warrants, concluding that MI5 had no case on which it could make an adverse recommendation to the Ministry of Supply.

It apparently took Hollis another six months before he picked up the story with his new boss Dick White, when he belatedly recommended to him that the Service had no objection to the establishment of Fuchs. It is not clear why White had not been more fully involved before this time, but he tried to cover himself as well, writing to Liddell on December 2: “I incline to agree with 104 [the Hollis minute], but in view of your previous interest in this case, I should like you to see these papers before action is taken on the lines suggested.” Action? What action? And what papers did he think Liddell had not seen? It was all a bureaucratic muddle.

However one interprets the bumbling that went on, it is hard to interpret Hollis’s actions as those of a Soviet mole overcoming the instincts of his superior officers. First of all, the status of Fuchs has to be considered. He was a UK subject, having been nationalized in July 1942, and was thus free to move around. Despite vetting concerns, his employment had been considered vital to the Tube Alloys project, and the DSIR (the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research) had overridden MI5’s concerns. Fuchs had returned from the USA with important secrets on atomic weaponry, and handed them over before the McMahon Act (forbidding the sharing of such with other countries) became law on August 1, 1946. At a time of nervousness about oppressing left-wingers early in Attlee’s administration, it would have required a very bold offensive by MI5 to recommend an aggressive pursuit of Fuchs (or others) without gaining incriminating evidence. Thus the period of surveillance was a necessary step in the project.

Yet the environment had changed. The Soviet Union was no longer an ally in the war against Hitlerism, and the Cold War was in full swing. The dangers of employing communists (with obvious loyalties to the Soviet Union) in sensitive positions with access to strategic information were well recognized by Hollis and his cohorts. The main hawkish thrusts, however, did not come from the senior officers, namely Liddell, White and Hollis (with Sillitoe almost certainly out of the picture), but from those with less to lose in their careers – the old stager, Jo Archer (no doubt getting advice from his wife), Collard, and the young Michael Serpell, perhaps anxious to make a name for himself. So the Warrants were initiated, and were then called off in May when they had produced nothing incriminating. Now, if Hollis had been a mole, he would have known that it would be safe for the NKGB to make fresh contact with Fuchs by mail or phone, and he would surely have informed his handler how Fuchs could be found. Yet Fuchs continued to flounder on his own initiative for several months. What do you say to that, Pincher old chap?

Liddell does not write much about Hollis in 1947. On July 2, however, he did enter an illuminating item in his diary, worth reproducing in full:

I discussed with Harry [Allen] his C. Division memorandum, with which I agree. I am certain that it would be a mistake to split up C. Division, or in any way to down-grade it. It should remain basically in charge of preventive security. As regards his successor, I thought TAR [Robertson] would be the best bet; an alternative was HOLLIS, who could ill be spared from B.1. As regards Jo ARCHER, there is no obvious successor. PAYNTER is not bad, but hardly has sufficient experience, and COLLARD is too young *. Harry thought that possibly Furnival-Jones could act as No. 2 to TAR and carry Jo Archer’s job as well. The only difficulty is Cookie, who will have to come under TAR, at any rate for everything except his wartime Portland Travel Control Group. Dick, with whom I have spoken, is in general agreement. He will, however, have to have someone to replace TAR. The only suitable officer that he can think of is Bill Magan. A possible alternative might be George JENKIN, although it is difficult to bring such a senior officer into an organization like ours; he would, of course, be a tremendous asset, as he would stimulate production all round the Empire.

[* Collard’s relative youth is a puzzle. He is recorded as being ‘Lieutenant-Colonel Collard’ in a visit to Arnold at Harwell in April 1948: see KV 2/1245. C Division took control of the Fuchs case until September 1949, when the fresh evidence of espionage demanded that it be handed over to J. D. Robertson in B2.]

The reader might feel that he or she has dropped into Mrs. Dale’s Diary, with the problematic ‘Cookie’ filing the office with gloom. (“I’ve been a bit worried about Cookie recently.”) It sounds as if someone (Hollis?) had wanted to carve up C Division on Allen’s retirement – which was not due for another year, by the way. Moving Hollis in might have addressed the latter’s possible status concerns, but it would sound like a down-grading in importance, unless Protective Security had been considered a more vital task than Counter-Espionage. The notes confirm Archer’s lack of fear in speaking up about Fuchs: Archer was to reach the retirement age of sixty that year, and left the office on September 22. On the other hand, why had Arnold been reaching out to Collard if he was still wet behind the ears? The shadowy figures of Magan and Jenkins seem to have been working for the Middle-Eastern group (SIME).

Nothing happened for a while: thoughts of further re-shuffling were in the works. On September 27, Liddell discussed with White and Hollis a problem officer in the B1C Research Section, a unit that his colleagues wanted to expand, so that a good deal of the work being done by the B2 sections could be better covered. The name of the unfortunate incumbent – a poor man-manager – has been redacted. Liddell thinks that Moreton Evans should take over. Reorganisation discussions went on. On October 7, Liddell noted that the ratification of B Division’s new structure could not occur until Sillitoe returned (from Canada) on October 25. On October 27, Liddell had a somewhat argumentative meeting with Sillitoe and White, where they discussed the new plans for B Division. Liddell recorded that ‘Tar’ Robertson would indeed take over B2. Meanwhile, Hollis’s involvement with conventional security issues was demonstrated by other activities. On October 10, he accompanied Liddell on a visit to see Sir Donald Ferguson, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Ministry of Fuel and Power, to discuss communist influence in the Miners’ Union, and a week later made a similar pilgrimage to Sir Arthur Street of the Coal Board.

In my more cynical moments, I ask myself: ‘What exactly did these senior MI5 officers do all day?’, what with their endless organisation planning, and dealing with querulous and dissatisfied officers, their attendance at JIC meetings, DG meetings and the like, their lunches at the Club with their counterparts from the Foreign Office, the troupes of visitors from overseas coming to chat to them, and, of course, their extended leaves (and diary-writing for one in particular). Did they ever work out policy and determine: this is what we should do when events change, and give clear instructions to their subordinates? It does not seem like it. They were continually reacting, and they constantly had to be on their watch to ensure their career longevity as they tried to gauge the temperature of their political masters. It was all so different from the frenetic months of 1940, when, in somewhat chaotic surroundings not eased by the eccentric interferences from Lord Swinton, MI5 officers were (according to John Curry) working long into the night.

Yet the recent moves afoot to increase Hollis’s authority would soon undergo a surprising, regressive blow. Before I describe the reshuffle of November 1947, however, I need to step back and summarize B1’s other activities during 1947.

Counter-Espionage: A 1947 Quartet

While Fuchs was the main theme for most of 1947, B Division’s year was coloured by the stories of four espionage agents: Peter Smolka, Engelbert Broda, Alexander Foote, and Ursula Beurton. While Smolka and Broda now constituted more of a distant threat, the dynamics of Foote’s dramatic return from Moscow, his surrender to the British authorities in Berlin, and his subsequent revelations cast a disruption of potentially career-damaging severity on MI5’s senior officers. His previous association with Sonia in Switzerland turned the spotlight on her and her husband Len Beurton. Yet any close involvement by Hollis with the whole exercise of challenging her is hard to detect.

After the war, it was a time of removal and return. The unsuspected spy, Fuchs, returned from the USA to British shores. On the other hand, most of the Soviet spies resident in the UK set their sights eastwards to Stalin’s satellite countries, where they no doubt aspired to help build his utopias. Litzy Philby and her lover, Georg Honigmann, went to East Germany. Peter Smolka returned to Vienna, where he hoped also to pick up his business interests. Broda, former lover of Edith Tudor-Hart, feeling threatened perhaps by his associations with Nunn May, in early 1947 also planned his return to Vienna. Yet it was not plain sailing for these exiles. The local Communist Parties treated them suspiciously: they had not fought in the trenches and sewers during the war. They had had a comfortable time riding it out, and were considered ‘bourgeois’ and ‘westernized’, even suspected of being capitalist spies. The Honigmanns and Smolka were especially threatened.

My analysis here has two main foci: i) the connections between the agents, and ii) the roles that the sections of B Division played in the investigations – especially that of Hollis’s B1. Smolka was by now an outlier. MI5 believed that he was still some kind of asset, and it consumed with alarm the updates on his behaviour and associations from Vienna that they received from MI6 locally in London. Broda came under fresh scrutiny because of his acquaintance with Nunn May, but there was little that the Security Service could work on. Foote was another matter entirely, however. Apart from his intimate and long association with Sonia in Switzerland, he had connections to Gouzenko, since the Rote Drei had had sought funding from Canada: Foote’s file shows that he displayed great interest in the events there. Yet the most remarkable disclosure arising from his length interrogations in the summer of 1947 is the breadth with which his confessions were promulgated within MI5 and beyond.

Both Hollis and Sillitoe were involved with the investigation into Broda, Sillitoe taking on the identity of B1A to write to the Chief Constables of Cambridge and Edinburgh in an attempt to track Broda’s movements. The ‘true’ B1A was Geoffrey Wethered, who liaised with MI6, while Collard of C2 was in communication with the Ministry of Supply. When Broda left the UK for Vienna in June 1947 – taking the secrets he knew with him in his head – not much more could be done about him. (Yet he made a return visit to the UK on April 15, 1948. By that time a fresh new suite of officers was in place.) On Smolka, G. R. Mitchell (another officer in B1A) was the lead officer on the case, and on November 7, 1947, he issued a report that Smolka was replacing Michael Burn as the Times representative in Vienna. When a brief flurry of interest surfaced in early 1948, B1A was still the unit following Smolka, although the B1A officer was one J. J. Irvine. What is clear, however, is that both studies were seen as coming under ‘Left Wing Subversion’, not ‘Russian and Communist Espionage’, which was the territory of B1B and B1C. It was a strange decision.

When, in early July 1947, Alexander Foote suddenly emerged from the shadows in Berlin, Hollis turned to his whole force to address the case. Foote, who had been a vital member of the Soviet Rote Drei network in Switzerland during the war, had made an audacious journey to Moscow, where, after interrogation and training, he had been despatched back to the West as an agent with a German identity destined for South America. In Berlin he had ‘defected’, or maybe more accurately ‘surrendered’, to the British Army, had been interrogated there, and had then been brought back to England on August 7 for deeper inquisition. By then his association with Ursula Beurton (as her name then was, the notorious Agent Sonia) had been determined, and Foote had also given testimony that she had been involved in espionage in 1941 and beyond. Serpell subjected Foote to intense questioning on July 20 and 21. (For a comprehensive account of Foote’s career, see https://coldspur.com/sonias-radio/ , Chapter 6.)

On July 25, Hollis decreed that Hemblys-Scales (B1C, Investigation into Soviet Espionage) should be in charge of the project, and the latter’s team (Serpell, Joan Paine, Jim Skardon, and an unidentified ‘JK’) took over the details. B1A, primarily in the shape of Baskervyle-Clegg, dealt with outside agencies, such as the Air Ministry, who might have had an interest because of Foote’s absconding from his employment with it, but declined an offer to discharge him formally. B1C, meanwhile, kept the US Embassy informed, and ensured that Thistlethwaite in the Washington Station was kept updated on progress. B1B, in the form of John Marriott and Ronald Reed, started the investigation into the Beurtons. On September 5, Reed urged that the Beurtons be interviewed soon, since Foote would shortly be released, and presumably might try to warn them. (In fact he had already done so, through an intermediary.) What is remarkable about the decision to follow up is that, as the Beurtons’ file KV 6/42 shows, it was taken by the group of White, Serpell, Marriott, Skardon and Reed. Hollis was not involved. Eventually, on September 13, Skardon and Serpell went to ‘The Firs’ at Great Rollright for the extraordinary interview with Ursula and Len that has puzzled practically everyone since.

Even Chapman Pincher cannot explain the indulgent manner in which the interview was carried out, and the subsequent inactivity, and he presents the evnets in terms that identify Hollis alone as the culprit. His chapter 37 in Treachery (‘The Firs Fiasco’) laments the ineffectualness of the whole campaign, and he points out how relieved Hollis must have been when he received Marriott’s report on September 20 that closed down the surveillance. Yet Pincher consistently writes about ‘the White-Hollis Axis’, as if his victim were in partnership with his boss, presumably crediting Hollis with powerful means of persuasion and influence over White. He casually overlooks the archival evidence that Hollis had for some reason been excluded from the critical decision-making of how to handle the Burtons. Pincher did not realize the irony of the situation, and did not consider that White may well have had other reasons for not taking the lid off the Beurton hotpot.

What is crucial to the overall drama is Foote’s testimony. The record in his Personal Files (primarily KV 2/1611-1613) is extensive, and constitutes a fascinating series of disclosures, ranging from facts about Foote’s relationships with Agent Sonia, the complicated goings-on in Switzerland, and the methods and techniques of the GRU cells there during the war. The most dramatic portion, however, is Foote’s revelations about Sonia’s divorce, marriage, and subsequent passage to the United Kingdom. Foote admits that he gave perjurious testimony to the Swiss court concerning Rudolf Hamburger’s adultery, thus enabling Ursula to marry Len Beurton. He also describes how, in the ‘Farrell’ business (Farrell being the MI6 representative in Geneva: see https://coldspur.com/special-bulletin-the-letter-from-geneva/ ), Len Beurton was allowed to return to Britain some time afterwards. Serpell was justifiably aroused by these disclosures. He had his last interview with Foote on September 19, where Foote’s perjury was again confirmed, and he recorded his opinion that he had not been at all surprised at Sonia’s nervousness six days beforehand.

Now one might consider these facts (as facts they surely must be, since they helped explain a lot about Sonia’s unique escape, and the declaration of them was very incriminatory for the man who issued them) would have been guarded very carefully, as they implicitly bore some menace for the roles and reputations of MI5 and MI6. Yet they were not only treated in a cavalier manner, they were promulgated inside and outside MI5. Even Serpell was party to the project. On October 16, he wrote a note to Hollis that ran as follows:

We spoke about the attached general account of Alexander Allan FOOTE’s case and its circulation to Office Representatives overseas. You wished to discuss the question with B.3. and I have annexed a draft covering letter for your signature when the circulation is determined.

B3 was responsible for overseas liaison, and it appears that ‘Tar’ Robertson had by then taken it over in addition to his role as head of B4, the general support section that included Watchers, Agents and Informers, and Technical Facilities. On October 20 Robertson hand-wrote a note that requested twenty copies of the report to be sent around the world to various offices, and he initialled his contribution as ‘B3’.

And the dissemination went further. The same day, Hollis instructed Serpell that the report could be given ‘verbally’ (of course, he meant ‘orally’) to the FBI. Serpell prepared a doctored version (i.e. one that omitted most of the English end of the story – except for Sonia – including the ‘Farrell affair’) for Thistlethwaite. The final version that went around the world to MI5 stations, nevertheless, was very explicit about Foote’s perjury, laconically recording simply that ‘in December 1940 SONIA succeeded in establishing herself as a British subject by marriage and left for the UK’. Any self-respecting intelligence officer should have immediately questioned how so challenging a journey could have been accomplished with such apparent ease. Yet the distribution was approved at the highest level. Dick White congratulated his team on the project, and on October 30, Hollis signed the memorandum on behalf of the Director General, with the B1C identifier, that proudly drew attention to B1C’s achievements in compiling an accurate account of Russian intelligence activity.

The very next day, a new wave of reorganizations occurred.

The November 1947 Reorganization

The evidence is clear from the Foote PFs: suddenly the assignments of the officers have changed. On November 5, Serpell has moved from B1C to B2B; likewise Paine. On November 10, Robertson is now B2; Hemblys-Scales has also moved from B1C to B2B. What is astonishing is that, as recently as September 27, Liddell had been writing about B1C’s expansion: now it was being transferred lock, stock, and barrel to another unit. Thus Hollis’s role was being dramatically reduced. The bare facts can be found in KV 4/161 & /162, which files record MI5’s organizational changes after the war. (Ewing, Mahoney and Maretta offer, in their very useful Appendix to MI5, the Cold War, and the Rule of Law, a summary of this re-organization.)

The announcement was made on November 1. The most important aspect of the reshuffling was the fact that two important segments of Hollis’s empire, B1B (‘Investigation’) and B1C (‘Information’) were moved across to B2, becoming B2A and B2B. Instead of non-Soviet espionage coming under Hollis’s wing, the most strategic functions were moved to a section that appeared to have no experience in dealing with the threat. ‘Tar’ Robertson, who had specialized in Double-Cross during the war, and the miscellanea of B4 since, was indeed appointed head of B2. Bagot’s B1D (‘International Communism’) became B1B, however, remaining under Hollis, and, in a bizarre twist, ‘a new B1D was formed, monitoring those foreign subversive groups in the UK formerly undertaken by B2A and B2B, not covered by B1A (left-wing counter subversion) and B1C (right-wing counter subversion), and the investigation of potential espionage cases’. That last clause hangs uneasily: what is it supplemental to?

This seems like a mess. Why would potential espionage cases be separated from important investigations into the prime Communist threat, managed by B2A? Ewing, Mahoney and Maretta have an answer. “Essentially, B1D was required to tackle those cases perceived as presenting less immediate threats to the defence of the realm, and to pass more serious cases on to B2. The section was also given responsibility for housing and controlling defectors.” Furthermore, in a Footnote the authors cite, in a passage that is worth reproducing in full, a report on a statement by White:

This incarnation of B1D had been established in November 1947 as a section wholly separate from Miss Bagot’s B1D – her international communism work continued, as noted above, under the designation B1B – and B1D appears to have been subsequently treated as a dumping-ground for roles that other sections would not take. In January 1948, White stated that it should monitor ‘foreign espionage activities in the UK other than those studied by B2A. However, having isolated for specialized study by B2A the potentially hostile ones, B1D’s responsibilities need not comprise more than the tackling of actual cases as and when they arise’.

A less useful mission given to the poor sap who had been handed this ‘dumping-ground’ would be hard to imagine. And what other countries or ideological bases apart from international Communism were carrying out serious espionage in the UK, pray?

Robertson’s appointment is also bizarre. The previous incumbent, John Curry, had been absent ill for a while, and Marriott had deputized for him. Why was Marriott not promoted? Was Robertson given a plum because he had expressed dissatisfaction, and may have been bored? It is possible, but why load on him immediately all the extra responsibilities of B1C and B1D that had been managed by Hollis? After all, Hollis had been presented as the expert on international communism (and Soviet espionage!) at the time of the Gouzenko affair, and Liddell had not so long ago reflected how Roger would be missed if he had to be taken away from his valuable work as head of B1. (One has to assume that Liddell frequently played to the gallery in his diary entries: he can be very equivocal about Hollis’s talents.) In any event, Hollis, as the rump of B1, had undergone a massive decrease in authority. Moreover, the expertise of Bagot (who had wanted to get away from his tutelage) stayed with him, when it would surely have made more sense to have her closer to the B2 units, and he was left with a mixed bag of non-Communist subversive activities to handle.

The fact that ‘Tar’ Robertson needed help is ironically revealed by what Anthony Blunt told his handler, Rodin (aka Korovin) in January 1948, soon after Robertson’s appointment. Nigel West and Oleg Tsarev report in The Crown Jewels (p 176) that Robertson had confided to Blunt that ‘the difficulty is that we can’t clear up anything about Russian espionage’, and had asked him to let him know if any useful ideas occurred to him. That Robertson would seek assistance from Blunt rather than his boss, Dick White, is amusing: maybe the message of frustration was something that Hollis had passed to him. That possibility had eluded West and Tsarev: they appear to be unaware that Robertson had recently replaced Hollis as officer in charge of Soviet counter-espionage, since they describe him as still being in charge of B4. In any event, Blunt soon afterwards reported that MI5 had stepped up its surveillance of Soviets when Hollis had departed for Australia, Blunt gaining his insights from ‘indiscreet Security Service personnel’.

What prompted this shuffle? I considered four major causes: 1) The status of Protective Security (C Division); 2) Discipline, namely the execution of the Foote/Beurton project; 3) The Exposure in Australia; and 4) Insurrection in the ranks. Something must have accelerated these changes, which were by all measures premature, certainly disruptive, and did not reflect a sensible allocation of resources.

- Protective Security: In this scenario, Sillitoe and Liddell regarded the needs of Protective Security as more important to the success of MI5 than Soviet counter-espionage. With Allen due to retire in the autumn of 1948, it was important to line up the best man for the job, and that officer was Hollis. In fact, he was publicly appointed on July 1, 1948, even though he did not take up the post until December. Yet that decision did not require such an early changing of the guard, and Hollis would have been under-employed for a while as he watched his colleague Robertson learn the ropes for a year or so. The dramatic reduction in authority would have constituted a strange signal to the troops, especially if the subject were soon to take on an even more important task. There was no need effectively to demote Hollis, and hand over much of his responsibility to ‘Passion-Pants’ Robertson, already disillusioned, and not familiar with the turf.

- Discipline: Within this hypothesis, Hollis was shown to have badly mismanaged the interrogation of Foote, and to have bungled the interview with the Beurtons. His careless eagerness to disseminate the details of the Foote disclosures to all and sundry was seen as irresponsible, and he had to be brought down a peg. Yet Hollis was not involved with the final strategy for handling the Beurtons, and the evolution of the Foote case appeared to have been received with acclaim by White and Sillitoe. Moreover, Sillitoe must have agreed with the decision to distribute so broadly the report that sharply highlighted the dubious practices of British Intelligence in Geneva. Again, this is a scenario that does not hold much water.

- The Exposure in Australia: As I shall explain soon, MI5’s agenda was rapidly overtaken by the need to investigate intelligence leakages in Australia. Attlee asked Sillitoe to investigate personally, and the Director General selected Hollis to accompany him, as Hollis had been one of the few officers to have shown him any respect. Thus it was essential to reduce Hollis’s workload as soon as possible. This otherwise attractive scenario falls down over chronology. The awareness of the security leaks appears to have reached Sillitoe only in late December, and, if anything had been whispered earlier, it would have been unlikely for Hollis’s name to come up as a player, or for any expectation to have arisen that he might have to be absent for months.

- Insurrection: While there is no direct evidence for such a scenario, I recall that Bagot, Marriott and Shillito had earlier expressed their frustrations in working for the uncommunicative Hollis, who tended to keep information to himself. There may have been a broad rebellion in B1. The sudden shift in perceptions by White and Liddell as to the health of Hollis’s section, with their readiness to expand B1C, followed by the quick compression of B1’s charter, suggests to me that they perhaps learned of dissatisfaction in the ranks towards the end of the Foote project. Thus the cobbling together of a revitalized B2 unit, under an officer broadly liked and respected, seemed the most appropriate fix, despite Robertson’s lacking in relevant experience. I judge this to be the most likely option.

A significant, but absent, part of this process is the role of Dick White. As the manager to whom Hollis reported, he must have had the lead in deciding Hollis’s future. His re-shaping of B1 and B2, including the introduction of the now rebellious and unsuitable ‘Tar’ Robertson, can only be categorized as bizarre. Its timing is bewildering. And the lack of confidence he thus expressed implicitly in Hollis as a leader represents a weird foretaste of his advice, in 1956, that Hollis should replace him as Director General.

Lastly, I for a while nourished a theory that Jane Archer might have been brought back into MI5 at this time. I see many clues. Jane was pressing Sillitoe and Edward Bridges for some kind of re-instatement, as she had lost her pension on being fired at the end of 1940. Liddell was talking to Vivian of MI6 in the autumn of 1947 about Jane’s future, and he would have been keen to see her return to the fold. Could Liddell have been preparing to bring Jane back to B Division? Yet again, as supporting evidence for the November reshuffle, the chronology does not work. On November 5, 1947, Jane was still negotiating furiously with Sillitoe and Bridges about her pension, and, with her tendency for making enemies by being very blunt in her demands and opinions, she was by no means assured of a future with MI5 at this time.

One or two cryptic entries in Liddell’s diaries do hint, however, that she may have been hired in some clandestine way in 1948. He describes speaking to an unidentified ‘B1’ in his diary entry for June 14, 1948, at a time when Hollis was still B1 – and Hollis was on that day in Washington with Sillitoe. Moreover, Liddell always referred to Hollis as ‘Hollis’ or ‘Roger’, as indeed he did later in the same diary entry. The announcement that Graham Mitchell would become Hollis’s ‘deputy’ in B1, pending the latter’s eventual transfer to head C Division, was not made until July 24. Thus this reference is very enigmatic. A correspondent has pointed out to me that ‘B1’ could well mean the whole group, and that Liddell was thus having a meeting with all of its members. But the context is very provocative. Liddell is following up a question that concerns proscribed organizations in 1933, and he goes to B1 to seek help. Who would have been around in 1933 to know about the list, and that it had not been kept up to date? There could not be many candidates, and it would not be much use addressing the whole group, would it?

Finally, I recall that, in the summer of 1951, Archer was evidently working within MI5, and active in the Philby inquiry, when she worked with Arthur Martin on compiling the dossier on Philby. See The Perfect English Spy, p 125.

The Sillitoe Era: Hollis in 1948

Roger Hollis’s morale could not have been high in November 1947. Two years ago, he had been hobnobbing with Presidents and Prime Ministers in the wake of the Gouzenko defection, and now, having been represented as the expert in Soviet communism, he has had his counter-espionage responsibilities stripped away from him. It must have been the nadir of his career. Maybe the C Division post had already been dangled in front of him, but it would have been an embarrassing twelve months before he would be able to assume its reins. And then, towards the end of the month, what eventually became a lifeline turned up. On November 25, Liddell first noted the initial conclusions about a security leak in Australia:

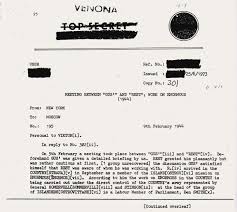

I gather that some progress has been made with Russian B.Js. * 300 Americans, headed by two experts of L.S.I.C. #, were working on the job in the U.S.A., and a considerable number were similarly employed in this country. Some success was achieved over a message in Australia, dated around 1945, indicating that a Government document, supplied by us to the Australians, had leaked almost in toto. The Department for External Affairs in Australia is probably responsible. This is disquieting, since so much of our information is going in that direction and experimental work on rockets, etc. is being conducted in Australia.

* ‘Blue Jackets’: a holdover from WWII, when Enigma messages were held in such.

# The L.S.I.C., London Signals Intelligence Centre, was a temporary name for GC&CS on its way to becoming GCHQ.

This was, of course, the first inkling of the VENONA project. Hollis was still involved with desultory matters at the end of the year, such as the final dispensation of the Fuchs investigation. Meanwhile, the tensions over the Australian leakage grew during December, and Sillitoe had to inform Prime Minister Attlee of the events at the end of the month. By January 14, Hollis was involved. On January 12, Liddell reported a meeting called by Sillitoe, at which White, Drew, Travis (of GCHQ) and Dunderdale were present. Attlee wanted Sillitoe to go to Australia and see Prime Minster Chifley about the leakage. With the situation so sensitive, and the Americans so suspicious of Australia’s reliability at a time when it was getting more involved with testing of nuclear weapons, MI5 had to act very cautiously in not divulging that the insights had come from VENONA. The true source could thus not be revealed, and a cover-story intimating that the intelligence on the leak had come from a defector, code-named ‘Excise’, had to be prepared. The task of drafting the report fell to Drew and Dunderdale, and they devised a cover story that eventually embarrassed Hollis

On January 14, the cover story was approved – but it contained a fresh twist, namely the inclusion of a second document. Liddell wrote:

There is no evidence that this second document did in fact reach the Russians: it has been included in order to give cover to the first document and to help Travis in getting agreement of the Americans to the proposal to warn Chifley. Hollis and I both objected, first that it would mislead the Australians in their inquiries, and secondly that if it reached the Russians it might cause them to think that the whole cover story was phoney. It was felt, however, that we should have to take a chance on this.