The main purpose of my visit to the U.K. this month was to attend the degree ceremony at the University of Buckingham and to receive formally my doctoral award. As many readers will recall (wake up at the back, there!), my thesis covered the subversion of MI5 by communist agents and influences at the beginning of WW II. A symptom of this institutional failure was the later indulgence shown to the Soviet spy Leo Long after he was caught red-handed passing military secrets from MI14 in 1943, my claim being that this ‘Sixth Man’ may have been even more dangerous than the pentad of Cambridge graduates that has gained practically all the publicity. (The latest issue of Christ Church Matters, the alumni magazine of my Oxford college, contains an article about my research, titled ‘The Moscow Plot’, and it can be viewed here.) Followers of my subsequent research on ‘Sonia’s Radio’ may also have noticed that I have hinted at the remote possibility that the 1956 death of Alexander Foote may have been faked by MI5 (with the connivance of SIS) to prevent his assassination by Soviet military intelligence. The relevance of these two items will become clear by the end of this blog entry.

On the first evening of my trip, after I had arrived early in the morning at the Battersea residence of my brother, Michael, and his wife, Susanna (who has courageously and gratifyingly recovered from her cancer treatment), Michael and I went to the Instituto Cervantes near the Strand to attend an interview with Professor Sebastian Balfour, Emeritus Professor of Contemporary Spanish Studies at the London School of Economics. Professor Balfour and Michael had become friends when they were both in hospital, and the Professor had very kindly ensured that Michael received special attention when he was in dire straits. I had met the Professor and his wife, Grainne, at Michael’s house on my previous visit, and was eager to learn what the Professor had to say about Spanish matters in the last century, and later even, right up to the secession attempts now being made by Catalonia. What with Philby’s association with Franco, Spender’s mission on behalf of the Comintern, Foote’s action with the International Brigades, as well as the whole sorry story of the Soviet-directed elimination of the anarchists, and the orchestration of the stealing of Spain’s gold by Orlov on Stalin’s behalf, the events of the Spanish Civil War were very relevant to my research area.

Professor Balfour offered us some excellent insights, skillfully weaving the experiences of Spain in the twentieth century into the fabric of today’s cultural and ideological dynamics. Moreover, at the party after the event, I was pleased to meet Mark Ezra and his wife, who were neighbours of the Professor. Mark turned out to be a film-producer, and I was happy to take his address as a possible contact for arranging a deal for the script (based on the central event of my thesis) that my friend and colleague Grant Eustace has been trying to place. Moreover, in one of those strange coincidences that tend to aggregate as one gets older, I discovered later that Mr Ezra had attended Ampleforth College, and had been educated both by Susanna’s father (Haughton) as well as by her first (deceased) husband (Dammann).

After the Spanish event, Michael and I took a taxi to Chelsea, where Susanna was winding down a dinner with four long-standing friends, all outstandingly bright professional women, and wonderful company.

Nicola, Nemeen, Mo, Janie & Susanna

The conversation was lively, and one of the friends (Mo, who is a psychotherapist) decided to issue nicknames to us all. I was given the cryptonym POLARBEAR, (surely in ignorance of my austere reputation as COLDSPUR), which prompted me to respond that my times must be numbered, as the beast ran the risk of soon becoming extinct. This was a highly enjoyable and lively end to the day, which had started by seeing me deplane at Heathrow at what was in fact 3 am in Southport, North Carolina (already on summer time), and which closed by my collapsing into bed at midnight local time.

I had arranged to meet Grant Eustace for lunch in Victoria the following day (Friday 10th), and was able to pass him the lead. Grant and I exchanged sympathies over the struggles with making headway in the worlds of publishing and the media, but maybe something will become of this opportunity. In any case, Grant is always working on some stimulating project, and I enjoy learning about his new ventures. On Saturday morning, I had to catch a train to Newcastle, in the North of England, since I was attending, as my more impulsive alter ego of HOTSPUR, the annual Listener Crossword Setters’ Dinner in Gateshead. I had not attended this event for ten years, but the opportunity was too great to pass up, even though I was a bit embarrassed by the mistake in my centennial Alan Turing puzzle of five years ago. I need not have worried: I was not booed on arrival. It was an excellent occasion, where I re-encountered some old friends, and established new ones. The pseudonyms of the setters often resemble the cryptonyms of agents working for Soviet Intelligence: thus my friend Ian Simpson (who was one of my testers) bears the same sobriquet (HOMER) as the Cambridge Spy Donald Maclean. The photo below shows Ian sitting next to Richard Heald, a renowned solver. THIRD MAN (Richard England, not Kim Philby), who holds the current record of most consecutive Listener puzzles correctly solved (103, I believe, and still active), was supposed to be in the photo, but he, who remembered me as a fellow London Society Rugby Football referee, somehow was recorded only in a short video-clip. (‘Third men’ customarily prefer being airbrushed out of history.) I was honoured to be sitting next to SHACKLETON (John Guiver), who won the prize for the best puzzle of 2016. This event is a very British affair, and a great institution, populated by smart, inventive and congenial people, who love words, and crosswords, and all the cultural trappings that accompany the Listener puzzle. But 2017 will probably be my last dinner.

Ian Simpson & Richard Heald

The Elusive Third Man (Richard England) (video not yet displayable)

Hotspur & John Guiver

I took the return train to London the following morning, arriving back in Battersea in mid-afternoon. That evening I was fortunate enough to meet the philosopher John Hyman, Professor in Aesthetics at the University of Oxford, who is also a friend of Michael’s and Susanna’s, and had been invited to dinner. John had expressed interest in my thesis since he knew Isaiah Berlin (indeed he had once been on a bus with him, and thus considered Isaiah and himself ‘fellow-travellers’) and asked me several penetrating questions. I was happy to discuss the implications of Berlin’s friendship with such as Guy Burgess, Lord Rothschild, and, most of all, Jenifer and Herbert Hart, since Jenifer had been Berlin’s lover, and Herbert had been a most important influence on jurisprudential philosophy, being acknowledged several times in Hyman’s recent Action, Knowledge and Will, a volume I might perhaps not have picked up otherwise. I prepared for the occasion by reading the most relevant chapters on the train from Gateshead, but (perhaps fortunately) we ran out of time before I could be questioned on the arguments. (I regret I am a bit slow on these matters: I am still trying to come to grips with ‘Freddie’ Ayer’s 1936 Language, Truth and Logic.) But again, a most enjoyable evening.

Monday saw me meeting my old friend David Earl, who picked me up at East Croydon Station, whence we repaired to a pub for lunch and caught up with each other’s news. David has always shown a solicitous interest in my research, and asked me again whether I had been ‘tapped on the shoulder’ over my subversive line of inquiry. I suggested to him that it might be a bit late for that, and that any such warnings would now only aid publicity for my forthcoming book. Later that afternoon, I went to Whitgift School, where I was able to see two long-standing friends, Tia Afghan, the Head Librarian, and Bill Wood, the Archivist, before preparing to attend the AGM and Annual Dinner of the Old Whitgiftian Golf Society, a group I had joined on a previous visit to the U.K. Some of the gentlemen attending I had never met before, a few I had played golf with, but I was delighted to see again some old colleagues from the rugby and cricket fields, such as Mike Wilkinson, Paul Champness, Alan Cowing, Howard Morton, and Jeremy Stanyard. It was another highly enjoyable evening: golf is thriving at the School, and while the Headmaster chose the occasion to give a rather supererogatory motivational speech, it did not detract from the sense of fellowship. Howard Morton kindly drove me home to Battersea.

Messrs. Stanyard, Wilkinson & Champness (centre)

Peter Abel (left) et alii

Work followed on Tuesday. I went to the National Archives at Kew, where I had to wait to get my Reader’s ticket renewed, and then hung around while my requested files were retrieved. My goal that day was to dig around in the records of the Radio Security Service to discover what attempts had been made to intercept unfamiliar and unauthorised radio traffic either being received or transmitted within the UK’s shores in the 1940s. I also managed to inspect the missing volume of the files on the Rote Kapelle: for some reason, the third volume of biographical information on RK members and affiliates had not been digitised, and thus I had been unable to download it from my home in Southport. When I brought this oversight to the attention of the Kew authorities a few weeks ago, they could not explain it, and committed to rectify the problem, but were in no rush to do so, especially as I was about to visit the Archives. I discovered several nuggets, some that addressed enigmas, some that provoked new ones.

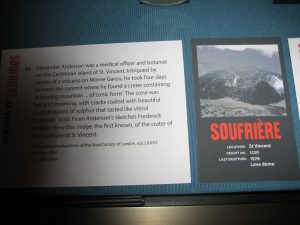

The next day saw Michael, Susannna and me driving to Oxford, where we were scheduled to be shown round the exhibition on Volcanoes at the new Weston Library of the Bodleian by its lead curator, David Pyle, Professor of Earth Sciences at the University. This visit had been arranged by another coincidence: I have been a Friend of the Bodleian for some years, and when I met Jessica Brown of the Development Office last summer, I had happened to mention that my wife Sylvia had been born in St. Vincent. A few weeks later, astutely recalling the connection, Jessica contacted me about the Volcanoes plans, saying that the eruptions of La Soufrière on the island constituted an important part of the coming exhibition, and would I be interested in it? I was able to inform her that Sylvia and I had trekked up to the top of the mountain in the autumn of 1978, whereupon our guide – who had never seen smoke emanating from the base ̶ wanted immediately to dash back down the mountain for fear it were about to erupt again. Moreover, I was able to extract from my files a report on the adventure that I had written back in May 1979, after the major eruption that occurred on Easter Friday. (See here.) The long and short of it was that I agreed to help fund a video and audio display about the Caribbean volcanoes in the transept space at the exhibition, and the personal attention of the kind and expert volcanologist, Professor Pyle, was our reward. The exhibition contained a remarkable set of accounts, illustrations, and maps from the Bodleian Libraries, as well some items borrowed from outside. I heartily recommend a tour: the exhibition closes on May 21.

La Soufrière at the Bodleian

Michael, Susanna & I on the roof of the Weston Library

We then moved on to Christ Church, my alma mater, where I had arranged a visit to the Library. Dr Cristina Neagu, who is keeper of the Special Collections, was able to show us a rich and assorted set of documents, from commentaries by Maimonides to recently discovered notebooks and publications by Lewis Carroll, as well as the remarkable Graz camera that is contributing to an exciting digitisation project at the Bodleian. The wealth of the Special Collections is extraordinary, and is being made more broadly available through the interpretation of scholars, and the efforts of Cristina and her team, supported by innovative digitisation techniques. This was another very fascinating experience, and we returned to our hotel at Peartree Road well stimulated, ready for some excellent refreshment and dinner at the Trout at Godstow.

No relaxation! The next day (Thursday), Susanna was seeing a friend in Oxford, so Michael drove us to Bletchley to spend a day at Bletchley Park, the wartime home of the Government Code and Cipher School (renamed Government Communications Headquarters at some stage during the war). While I knew a fair amount about GC&CS from my reading (especially about the analysis of ENIGMA traffic), I had never visited the place itself. For me, much of the inspection of the various huts was less than overwhelming, but the experience was enhanced by a brief tour of Bletchley Park House itself (in which the office of its chief, Alastair Denniston, stood), and capped by a remarkable exhibition in Block B, where a moving account of Alan Turing’s life and tragic end was given, as well as a crisp and articulate demonstration of a reconstructed ‘Bombe’ at work. An ENIGMA message was decrypted with the help of a ‘crib’ that relied on the fact that no letter could ever be encoded as itself, the multiple wheels rotating until a trial set of complete matches was made. The (volunteer) demonstrators performed a superlative job: one of them told us that her father had worked at Bletchley Park during the war, and then, after learning Russian, had moved on to manage English Accessions at the Bodleian. But the exhibition was also a little coy about the controversies that still surround wartime security and management. For example, in the Visitor Centre, three plaques show Stewart Menzies (head of SIS, to whom GC&CS reported), Alastair Denniston (who led GC&CS from 1921 to 1942), and Edward Travis (director from 1942 to 1952). Menzies is graced with his ‘Sir’, but with no dates. Denniston and Travis are both given their years of birth and death, but no titles, although Travis was given his knighthood a few months after his appointment, while Denniston was shamefully never given one. Maybe embarrassment over this snub still lingers.

Susanna took the bus from Oxford to Buckingham to join us on Thursday evening, where we were staying in preparation for the degree ceremony on Friday. Friday turned out to be the coldest day of my stay: I had to pick up my cap and gown in good time before setting off for a meeting with Christopher Woodhead, the editor at Buckingham University Press. We had not met in person, so it was good to discuss across the table plans for the book based on my thesis ̶ indexing, illustrations, cover, launch. We appear to be on target for a September publication. And then ̶ off to the Church of St Peter and St Paul for the secular Convocation for the Conferment of Degrees. This was a very well planned and executed ceremony, one of five held over two days, so that each graduand could receive a personal introduction. Sir Anthony Seldon, Vice-Chancellor of the University (and also my internal examiner) gave a bravura performance in orchestrating the ceremony, which was enhanced by a wise and amusing speech by Lord (Mervyn) King, former Governor of the Bank of England, and honorary graduand for the School of Humanities. It was followed by an excellent buffet, where we were pleased to be joined by my supervisor, Professor Anthony Glees, and Sir Anthony Seldon, as well as by the MP for Buckingham (and Speaker of the House) John Bercow. The whole event was a grand example of British pluralism: persons of many countries, creeds, colours and cultures (and ages) coming together (in a Protestant church) to celebrate academic achievement and to be individually recognised, before dispersing to their different groups and associations. Pluralism, not multi-culturalism, in the spirit of the endorsements in my thesis. A very satisfactory day, and I am proud to be associated with the sole independent university in Britain with its motto ̶ Alis Volans Propriis (‘Flying On Our Own Wings’). I was sorry that Sylvia and Julia could not be there to witness it, but the support of Michael and Susanna meant a lot.

Sir Anthony Seldon & Michael

Susanna & John Bercow

So then back to London, and champagne. The next day I had a reunion of the 1965 School Prefects at Whitgift, held at a pub near Hyde Park Corner. On my way there, I saw Howard Morton, who lives in Chelsea, and I was introduced to his charming Rwandan-born wife, Yvonne, and son, James. Twelve prefects attended the lunch: three of them I had not seen in over fifty years. Of course we each had perfect memories of what happened all that time ago, even if they did not all coincide, but Peter Kelly had brought along a few artifacts to provide documentary evidence, and to provoke lively discussion. We all fondly remembered our former leader and Head Prefect, John Knightly, who had sadly succumbed to cancer a couple of years before. I was sorry that not all could make the event, but Peter kindly arranged it at fairly short notice, and it was good to see so many old friends again. One remarkable fact that arose from the occasion was that Andrew Jukes (one of those whom I had not seen for fifty years) told me that he was in Washington (where his father worked in the Embassy) at the time that Burgess and Maclean absconded in 1951 . . .

Sunday was a day off. I needed a rest, and to catch up. On Monday morning, I took the train to Minster ̶ between Canterbury and Ramsgate ̶ to have lunch with Nigel West (Rupert Allason), the doyen of writers on intelligence and espionage matters. I have read (and own) several of his books, but I keep encountering vital titles that I have overlooked and need to read. Nigel had attended the seminar I held at Buckingham a few years ago, so I was able to update him on the progress of my research and conclusions. We covered a lot of ground, including ELLI’s identity, Sedlacek and Roessler, Alexander Foote and Claude Dansey, the mistreatment of Denniston, the ISCOT program, and Sonia’s broadcasts. (Nigel once interviewed Sonia.) Nigel is not surprised by Denniston’s lack of a knighthood, pointing out that neither R. V. Jones nor Commander Godfrey was thus honored, but I continue to maintain that there is a deeper, murkier story behind the insult. Nigel also explained to me the reason why one’s effects are checked before entering the Archives at Kew: an academic had been detected inserting falsified documents into files, and then claiming breakthrough ‘findings’ some time later. (Not in my field, I hope.) That story can be inspected in West’s latest book, Cold War Counterfeit Spies. I was also very happy to meet Nigel’s charming wife, Nicola, a professional violinist, and the time went all too quickly before I had to catch the train back to London.

I needed one more day at Kew, so on Tuesday I caught the train from Clapham Junction to Richmond, switching to the ‘Underground’ to Kew Gardens, with an easy walk to the National Archives. I had a few files I needed to re-inspect, namely Dick White’s apologia to the Cabinet Office, the records of Leo Long, as well as the Kuczynski files that are not available on-line, in order to catch any details I had overlooked beforehand. I also discovered another intriguing RSS file, which included a highly provocative 1943 letter from Richard Gambier-Parry (head of Section VIII in SIS) to Claude Dansey, requesting his support in an attempt to tighten up radio security in the light of unauthorized foreign traffic from England. This was interesting, since Guy Liddell of MI5 Counter-Espionage frequently complains about Gambier-Parry’s lack of concern for such matters, while Dansey has never been known as showing much interest in wireless technology. Gambier-Parry also wrote, alongside SOE, about a unit named ‘P5’, which I had not encountered before. (The structure of wartime SIS is a highly confusing topic: the authorised historian of SIS Colin Jeffery suggests that P5 was a group liaising with Vichy France, while Phillip Davies indicates it dealt with the Polish government-in-exile and the Free French, which is a much more likely scenario.)

Before I left Kew, I bought a copy of West’s Cold War Counterfeit Spies, as well as Peter Matthews’ SIGINT: The Secret History of Signals Intelligence 1914-1945, which appears to fill an important gap in the literature by concentrating on German interception and decryption techniques. From a quick scan, I noticed that Matthews makes the confident assertion (on p 196, though curiously without providing a reference or source, or even listing Foote in the index) that Alexander Foote was working for SIS in Switzerland, and passing on to the Soviets the valuable ULTRA information. (This is a hypothesis I am attempting to prove in ‘Sonia’s Radio’.) Thus casually do narratives get confirmed in the historical record, so I was naturally intrigued in the evidence after which he came to this conclusion, which directly contradicts what Professor Hinsley, the authorised historian of British Intelligence in WWII, has written about the release of ULTRA information to the Soviets. I look forward to reading the work from cover to cover, but have already succeeded in making contact with Mr. Matthews, and he has just informed me that he was actually with the Army in Berlin when Foote defected there in 1947! (He also carried out at that time several interviews with German radio intelligence officers.) He has promised to inspect his files to find out what sources confirm the impression he had at the time. But I certainly agree with him in one respect: Foote’s life story ‘could fill another book’.

Time to come home. I left Battersea for Heathrow at 5:30 on Wednesday in order to catch my 8:50 plane to Charlotte. It left at 9:30, and arrived half an hour early, which can be explained only by extraordinary tailwinds, or a padded schedule that leads to improved on-time arrival records. So I had plenty of time for my connection to Wilmington – too much, in fact. The plane coming in from Columbia, SC, was delayed because of maintenance problems, so that, instead of leaving at 4:10, it taxied off to the runway at about 7:00. As we were about to take off, the pilot announced that we would have to return to the gate since one of the flight attendants would otherwise exceed her working time for the day. This was doubly ridiculous: American Airlines should have known what was happening and made a decision beforehand, and the policy that a flight attendant would be dangerously overworked, having spent three hours in Columbia presumably doing nothing, and when the 30-minute flight to Wilmington does not even allow for serving drinks in cabin class, is an example of regulation at its most absurd. Furthermore, we then waited another half an hour until the replacement crew member arrived, while American Airlines told us nothing. What about regulations helping passengers? By the time I arrived home, I had been travelling for twenty and a half hours – something my doctor has advised me not to do. Of course, I do not seek expensive regulations to support frustrated passengers. I want choice of airlines, and less government interference when safety is not an issue. But the options are currently few without even longer flights and journey segments.

Lastly, a strange coincidence. On the train to Newcastle on March 11, I had started reading Charles Cummings’s The Trinity Six, an intelligence thriller about an academic, Sam Gaddis, who chases down a story about a notorious ‘Sixth Man’, and even encounters, at the National Archives, a beautiful SIS officer disguised as a helpful employee. The death of the Sixth Man turns out to have been faked by MI5/SIS, so that his existence can be concealed from the Soviets, who have even more interest than SIS in shielding the public and press from the real story behind his betrayal. I recommend the book wholeheartedly. What is noteworthy, however, is that Chapter 26 begins with the following sentence: “Forty minutes earlier, Tanya Acocella had been passed a note informing her that Dr. Sam Gaddis – now known by the cryptonym POLARBEAR because, as Brennan had observed, ‘he’ll soon be extinct’ – had visited an Internet café on the Uxbridge Road and purchased an easyJet flight to Berlin.” Is this art imitating life, or vice versa, or simply a normal occurrence in the world of spooks? I had never met Susanna’s friend Mo before, she knew nothing about me, and I had not opened a page of Cummings’ book at that time. Gaddis does not fall victim to the multiple murders being carried out by the Russians, which is a good sign, I suppose: on the other hand, no sultry temptresses welcomed me at Kew. Yet I suspect that it will be MI5 who may not be very happy with me when my revisionist history of that institution comes out this autumn. Is POLARBEAR a marked man? My friend David may think so. I arrived in Britain, however, on my UK passport, and left on my American one. This highly sophisticated ruse ̶ one learned from my handlers ̶ may have thrown them off the scent. POLARBEAR landed, but never took off again.

This month’s Commonplace entries appear here.